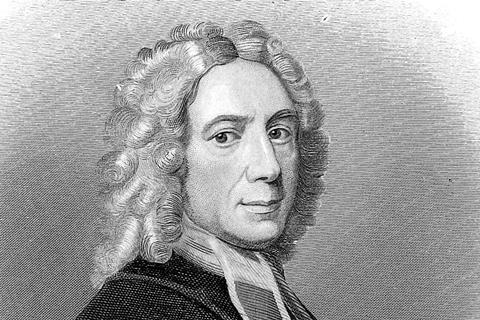

This year marks 350 years since the writer of ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’ was born. Dr Daniel Johnson takes a closer look at one of Isaac Watts’ lesser-known works

Alright, you lot in the back row, stop sniggering. This is serious stuff.

2024 is the 350th anniversary of the birth of hymn writer Isaac Watts. Watts is most famous for ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’, ‘Joy to the world’, and ‘O God, our help in ages past’. In his lifetime, he was one of London’s most famous pastors, and his hymns went on to dominate congregational singing for the next two centuries.

One of his lesser-known hymns is ‘Blest is the man whose bowels move’. It was published in 1719, and is based on Psalm 41:1, which reads: “Blessed is he that considereth the poor: the Lord will deliver him in time of trouble’ (KJV).

Watts’ hymn became: “Blest is the man whose bowels move / And melt with pity to the poor / Whose soul by sympathizing love / Feels what his fellow-saints endure.”

Obviously, to modern ears, talking about bowel movements carries very different, more lavatorial, connotations. I’ve spent nearly a decade researching Watts, for both my Masters and my PhD, so why am I talking about this hymn when there are more obvious (more sanitary?!) hymns to write about?

The answer lies in a series of sermons entitled Bowels Opened, published in 1639, from the Puritan preacher Richard Sibbes. The sermons were a study of the Song of Songs, a collection of poems attributed to king Solomon which are either read as romantic, even erotic songs between two lovers, or an allegory of the love between Christ and the Church.

Watts didn’t just want his hymns to express truth. He wanted his hymns to help people feel the truth

The bowels, in early modern language, were where you felt your deepest sympathy and tenderness. We talk today of a “gut feeling” – something visceral, deeper and more powerful than words. Something can be described as “gut-wrenching”, not because it’s a biological experience, but a deeply emotional one. To talk about the bowels moving is to talk about your emotions being affected in a powerful way.

And this gets us to the heart of Watts’ hymn writing.

Watts explained, “let us remember that the very Power of Singing was given to human Nature chiefly for this purpose, that our warmest Affections of Soul might break out into natural or divine Melody, and the Tongue of the Worshipper express his own Heart.”

Watts didn’t just want his hymns to be about expressing truth – important as that was to him – but he wanted hymns to help people feel the truth.

There’s a story which says that Watts was walking home from church with his dad, and he complained about how boring the hymns were at church, so his dad told him to write something better. This story almost certainly isn’t true, sadly. But, Watts was deeply frustrated with the ways churches sang. He opened his preface to his Hymns and Spiritual Songs like this: “While we sing the Praises of our God in his Church, we are employed in that part of Worship which of all others is nearest akin to Heaven; and ‘tis pity that this of all others should be performed worst upon Earth…to see the dull indifference, the negligent and thoughtless Air, that sits on the faces of the whole Assembly while the psalm is on their lips might tempt even a charitable Observer to suspect the fervency of inward Religion.”

In other words, people look so bored when they sang that you might not even think they believed the Gospel.

Singing, for Watts, was designed to stir up godly affections. If singing truth didn’t lead you to feeling more intensely, you weren’t singing right. Elsewhere, Watts wrote that when we sing, “spiritual affections are excited within us”. So, for Watts, one of the ways of fulfilling the command and receiving the blessing in Psalm 41 is to sing about it, because singing about compassion transforms the affections and makes the singer more compassionate.

If singing truth didn’t lead you to feeling more intensely, you weren’t singing right

In another of his hymns, based on Psalm 35, Watts wrote about David’s love for his enemies, but went on to say that “the love of Christ to Sinners” is “typify’d in David”. The final verse of that psalm is: “O glorious type of heavenly grace / Thus Christ the Lord appears / When sinners curse, the Saviour prays / And pities them with tears.”

In Matthew 14:14, when Jesus is described as being “moved with compassion” before healing the sick, the Greek word literally translates, “to be moved to one’s bowels”. What Watts gives us in these hymns is an example of how to become more like Jesus. By singing the truths of scripture, that should not only change the ways we think, but it should change how we feel. Singing, says Watts, is given to us to help us feel more passionately, more intensely, more generously, more Jesus-ly. This is why the one who’s bowels move is blessed. They’re becoming more like Jesus.

Elsewhere, Watts wrote that when we sing, ‘spiritual affections are excited within us’.

No comments yet