Having followed Lindsay Hamon and his giant twelve-foot wooden cross around Cornwall, Emma Fowle reflects on the powerful lessons on evangelism she’s learned from his unusual act of public witness

Appearances can be deceiving.

For many of us, if we were to think about street evangelism, we may consider those who do it unkindly. They must be weird, we reason, perhaps in an attempt to shelter ourselves from the possibility that God may ever demand such boldness from us. No one wants Jesus shoved in their face when they’re waiting for a bus or trying to get the kids to school; it probably puts people off Christianity rather than drawing them towards us.

Some of us look at street preachers and think: That could never be me. I’m not confident enough. Perhaps we reason that we’re introverts, God made us that way and he wouldn’t demand more of us than we can give or want us to feel so uncomfortably out of our depth. We’re not called to that sort of ministry; that’s someone else’s job.

If we’re honest, these quick reactions against street evangelism are sometimes more about letting ourselves off the hook than any sort of reflection on how God wants to work through us.

We often teach, talk and read about the upside down nature of God’s kingdom; the beautiful grace found in his surprising way of doing things. It is so often the polar opposite of what we would choose.

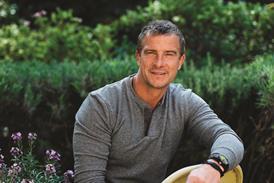

Sitting in a church café with Lindsay Hamon who for decades has walked the streets of the UK – and far beyond – with a twelve-foot cross, talking with people about Jesus, the unexpectedness of God strikes me once more.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t a man with an infectious laugh and a twinkle in his eye – and a surprising lack of surety in what he is doing. “Do you ever feel nervous?” I ask as we drink our coffee and prepare to go out on the streets. “Always,” he laughs. Does it get any easier? “No!” he says, laughing even more. “I’ve been doing this for 40 years and I still get butterflies every time.

“There are days that you really don’t feel like it,” he adds, and our photographer, Beth, chips in: “It’s like sea swimming!” she says. “My husband says you always feel better afterwards.”

“Yes!” agrees Lindsay, and there is that infectious laugh again. “You always feel better!”

About town

If I had any preconceptions about what a man who shares the gospel with total strangers in pubs, clubs and railway carriages would be like, they vanish within minutes of meeting Lindsay.

“What’s your approach?” I want to know. “Do you have a standard set of questions?” He smiles kindly and shakes his head. “Everyone is unique,” he says. “God meets people where they are. If I try to pre-empt it too much, it just doesn’t work. It becomes a bit cardboard – d’ya know what I mean?”

But that isn’t to say Lindsay doesn’t prepare. Each time, before he goes out, he spends an hour in prayer, pacing the front of the church and asking Jesus for help. “When I do that, if often feels like the Holy Spirit just rolls the red carpet out for me,” he says.

God’s goal is not that we would succeed at evangelism, but that we would live in relationship with him

As we take to the streets of Newquay, a seaside town in Cornwall renowned for its surf, stag parties and summer influx of tourists, the sun is shining. Next to the church is a Turkish barber shop and Lindsay stops to speak with two young Muslim men who work there. I ask them what they think of this man who carries his cross around town and talks to them about Jesus. “We are different religions,” one says, “but we talk as friends.”

They seem happy to let Lindsay pray for them and, as they embrace, a couple stop me to ask what this man is doing with a massive cross. This, says Lindsay, is the point of the 20kg of wood that he has touted, on its singular wheel, around the UK, Europe, Asia and as far away as New Zealand, for the past four decades. Inspired by Arthur Blessitt, who famously carried his cross to every sovereign nation on earth before passing away earlier this year, Lindsay says that as well as being a very visible witness to Christ’s death and resurrection, it is a great conversation starter.

The couple are on holiday from London, they tell us, and hugely excited to meet a fellow Christian. He is a lifelong Catholic, she was recently baptised. They share some of their story and Lindsay ministers to them, praying that their faith would be deepened and they would be refreshed by their holiday. Then they dash to catch their bus, calling and waving over their shoulder as they go.

Not everyone is open, of course, but I am amazed at how many are. A Ukrainian lady at the bus stop is not much interested in talking, and Lindsay moves on with a wave and a smile. “You know, when it says Jesus was a friend of sinners, it didn’t say all the sinners became wonderful Christians,” Lindsay remarks. It’s a healthy reminder that this is not a numbers game, and that our responsibility is not to ‘convert’ people but to love them and share the hope of the gospel.

A young man on a bench is clearly under the influence of drugs and his jacket is torn. “I want a cross,” he tells us. “A special one. I’m gonna get my jeweller to make me one.” He wants to talk but I am not sure what he understands in his inebriated state. Lindsay tries to direct him towards a local church that can offer practical help. We pray for him and keep walking.

This is the shadow side of rural life; the homelessness and addiction that blights the picture-postcard scene most have of Cornwall. Yet Jesus is here too. “Take me to the alley” sings Gregory Porter in his 2016 jazz hit of the same name, sung in Jesus’ voice: “Take me to the afflicted ones / Take me to the lonely ones that somehow lost their way / Let them hear me say / I am your friend.” Friendship – it sounds so simple. But perhaps, more than anything, this is what we need to be offering.

A young woman sits on a bench with her sunglasses on, listening to music by the beach. She’s never going to want to talk, I presume as Lindsay approaches her, but then she is whipping off her headphones and shaking his hand. “My boyfriend knows you!” she says. “He loves talking to you.”

She is not a Christian, but like a surprising number of unchurched young people, she has been thinking about faith and is definitely on a journey with it, she tells us. Lindsay hands her a tract that explains the gospel message. “Thank you for this,” she says, with sincerity. “And thank you for stopping to talk to me.” Lindsay tells her they’re sure to meet again. And if she wants to know more, to pop into the café church just up the road on the high street.

Lindsay is deliberately in Newquay on the same day every week and, because of this, locals get to know him. He can arrange to meet with people for further discussion or prayer, and they know where to find him should they want to chat about faith.

Next, we pass a group of men, also in their early 20s. They’re on holiday, but one peels away when Lindsay says hi. “Are you a Christian?” Lindsay asks. “Yes,” says the young man. “Oh, great! Tell me about your story.” The lad explains that his conversion was recent, alone in his bedroom with a Bible. He doesn’t much like organised religion but, somehow, he’s fallen in love with Jesus anyway. “Can I pray for you?” Lindsay asks, and the two put their arms around each other. His friends look on in bemusement, but he doesn’t seem to care. It is a holy moment.

A newfound spiritual openness among the younger generation is becoming so obvious that even secular newspapers such as The Times are reporting on it. Here on the streets, I’m witnessing this in real time. God is drawing a generation to himself – and it’s often despite the Church, rather than because of it. Young people are hungry to find out more about God. But where are those who are bold enough to meet them where they are? To take the chance on starting a conversation that may go nowhere – but that might be the answer to one person’s prayer?

As the morning unfolds, the sheer diversity of people, circumstances and conversations that we witness impresses and amazes me. The young mother with two small children who says she is a lapsed Catholic and is happy to take a tract. An Afghan couple sitting on a bench, a pushchair beside them and a small child asleep on their laps. They came to the UK a year ago, after their country fell to the Taliban. He was an interpreter for the British forces; now he works as a school cleaner. Language is a barrier, but Lindsay gives them a gospel in Farsi from a pouch around his waist – he carries the Christian message in 18 languages when he goes out on the streets. They are visibly moved when he prays for them.

Later, I ask Lindsay how he decides what to say to each person. “I always think: If I met Jesus in the street, what would he do? I think he would make me feel like I’d met with God somehow. That’s what I feel we’re called to be, representatives for Jesus.

“Jesus always dealt with people differently, he didn’t have a prescriptive way of talking to people. So really you want to be asking: how can Jesus help this particular person? What do they need?”

He points back to the family from Afghanistan. “I felt the best thing I could do is pour love,” he says. “I’m not thinking: Oh, I’ve got to run through this particular set of questions – although I’m not knocking that. I just hope they feel God’s love through me.”

Passing it on

The following week, I join Lindsay in Truro, Cornwall’s only city. We meet in a retail park next to the hospital. On the other side of the busy dual carriageway is the county’s largest post-16 college. As we walk past McDonald’s, the bus stops and pedestrian crossings are full of students, staff, hospital workers and shoppers.

This time, Lindsay is with a team of five others, including 16-year-old Charlie, who joins him every week on his only day off from his own studies at another college some 26 miles away. After receiving a prophetic call to evangelism, he’s here to learn from Lindsay, he tells me – although he seems pretty confident, immediately getting stuck into conversations with other students at the bus stop.

Later, another student, Jacob, joins us. He, too, counts Lindsay as something of a mentor. When he started college, he was looking forward to having more independence, he tells me. He wanted to be popular and go to parties, but found that life was lonely. “And so then, I’m like: I can either walk towards Christ, or towards the world. And I just felt drawn to Christ,” he says.

He met with Lindsay, who encouraged him to start a Christian Union. Six people grew to 20 at the end of the first year; now they regularly welcome 40-50 young people each week, many of whom are not from church backgrounds or Christian homes.

People are hungry to find out more about God. But are we bold enough to meet them where they are?

Wearing Chelsea boots, a flat cap and camouflage jacket, Charlie is a typical Cornish farm boy. Jacob, in a tracksuit, durag and chunky silver cross on a chain, couldn’t be more different. Yet here they are, standing side by side on the pavement outside college, sharing stories of God’s work in their lives and contending for their generation together. In a world that often feels more fractured and divided than ever, it’s a beautiful sight.

It is also testament to the more enduring element of Lindsay’s work. While many of his walks overseas may be one-off events, passing through a place never to return or know the fruit of the seed his presence has planted, here he is regularly investing. Week in, week out, he faithfully returns to the same locations, praying for places, building relationships with locals and teaching others – through example or practice – what it looks like to be bolder in their own witness.

Teenagers can be an intimidating bunch – some smirk and avoid eye contact; others listen intently while their mates pull faces at them from behind Lindsay’s back. He sits down with one in the bus shelter and points out verses in the Bible that he has highlighted in advance.

Lindsay knows what people are thinking: Oh, that guy’s a nutcase, carrying a twelve-foot cross. But he has learned to use such prejudices to his advantage. “In a way, that’s when humour kicks in,” he says. He tells a story of an occasion when he was struggling to communicate the gospel eloquently: “I remember this guy saying: ‘What you trying to say? Have you forgotten your lines or something?’ I said: ‘I ain’t got no lines! That’s the problem.’” He laughs raucously. Not taking himself too seriously can often break down barriers and build connections: “You start relating to that individual where they’re at.”

His self-deprecation is disarming, but it is also genuine. He loves people far more than he cares what they think of him. This is what drives his evangelism, and the people he meets seem to respond to that warmth.

Depending on God

What have I learned from my two days on the streets with a man and his giant wooden cross?

Firstly, flexibility. He doesn’t use a script but treats every individual differently. “How do you choose who to speak to?” I wonder aloud. “I’m ducking and diving with the Holy Spirit,” he tells me, trying to stay sensitive to the prompts and leadings of the one who goes before him. Sometimes he feels strangely drawn – or strangely repelled – by a person and has learned to trust these instincts. “Why get your head bitten off?” he says. “Jesus said: ‘Shake the dust from your feet’” (see Matthew 10:14).

As he walks with his cross, Lindsay’s interactions with people are many and varied. A nod of the head. A simple: “Hello!” Eye contact with a crowd of kids, scanning for who will look back, who might want to talk – or who clearly doesn’t. All of these micro-connections open the door to a potential conversation. Are we open to being interrupted by God like that? Are we willing to stop and have a conversation?

Secondly, dependence on God. “Sharing Jesus is a supernatural thing. It’s the Holy Spirit who does the work,” Lindsay says. We may know this theologically, but in our humanness, strategies, set questions and plans can help us feel in control when it comes to our evangelism, either personally or corporately. Lindsay is clear that this isn’t always a bad thing. “There are some questions that start getting to the heart of the gospel, you know: ‘If you died today, would you know that you’re going to heaven?’” he says.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t a man with an infectious laugh and a twinkle in his eye

But if the script becomes a comfort blanket or stops you relying on God and turning to him first, it is a problem. “The moment you start getting really super-confident is when you’ve actually lost the dependence,” he says.

You might think that, at some point in our walk with God, we would learn that one simple fact. But no matter how many times I experience it, I am quick to forget: God’s goal is not that we would succeed at prayer ministry, evangelism or healing, but that we would live in relationship with him. His priority is not providing us with a checklist or cheat sheet to short circuit the process, but to draw us ever closer to himself and to help us become more like him.

Thirdly, presence. When we pass through a place, our presence – or rather God’s presence within us – should change the spiritual atmosphere, even in ways that do not make sense logically. That is what I witnessed on the streets with Lindsay. What does a white-haired man in his 60s have in common with college kids at a bus stop? Why should a total stranger receive him warmly, open their heart to him on a street corner? At times, it’s like people can’t resist him, despite themselves – and I would like to think that this is the genuine love of God for all people that he carries. It is “the fragrance of Christ”, described in 2 Corinthians 2:15 (NKJV).

Lastly, openness. We seem to be hearing more and more reports of unchurched young people turning to Christ, but Lindsay says that he’s also noticing a wider, more general friendliness towards the gospel. “I’ve been saying similar stuff for nearly 50 years,” he says. “But what I’m finding is that it’s a bit like in the parable of the sower – there is more good soil.”

May that opportunity to plant seeds in good soil be one that every cross-carrier grabs hold of this Easter.

All photos (c) Beth Druce

No comments yet