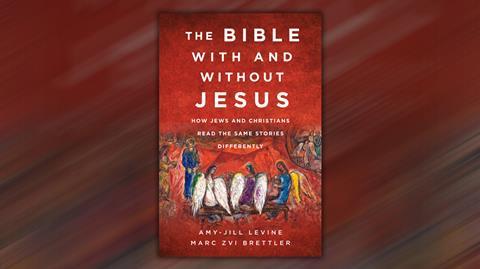

If you want to understand why Jews read the Bible in the way they do, then The Bible With and Without Jesus may be worth a read, says Lois Tverberg

We live in a rare time of openness, when Jewish scholars feel welcome to write about the Bible for an audience of both Jews and Christians. Both communities wonder how the common scriptures that we share can be read so differently by the other. In The Bible With and Without Jesus, two Jewish scholars attempt to answer that question.

Amy-Jill Levine is a Jewish New Testament scholar and Mark Brettler is a highly-respected Jewish scholar on the Tanakh, which is what Jews call the Bible and Christians call the Old Testament. Together they endeavour to explain to both Jewish and Christian communities how the other one reads the Jewish Bible, showing multiple ways that texts can be read. The point of the book is to present both sides and not to promote one interpretation as the right one.

They endeavour to explain to both Jewish and Christian communities how the other one reads the Jewish Bible

The usual pattern of each chapter is to open up a passage, point out where Christians find their ideas, and then explain why Jews don’t read the text this way. Then the authors explore a wide variety of Jewish viewpoints and include some imaginative midrashic sermons too. In that light, the Christian reading the text seems to fit in as another interesting ‘spin’. This approach won’t feel very affirming to traditional Christians but will likely satisfy Jewish readers.

Strengths and weaknesses

One strength of this book is the even-handed way that Levine and Brettler present the conflicts that have gone on between Christian and Jewish communities. Both groups have used prooftexts to produce angry polemics against the other, and both have woven arguments into sermons and commentaries. The authors note many Jewish teachings that include jabs against Christian ideas. But then they follow by noting where seemingly Christian ideas surface in Jewish texts down through the ages, either from the influence of Christianity, or from traditions that lingered through centuries from when some early Jews believed in Jesus.

It’s surprising that the authors don’t support the usual Jewish response to Christian missionaries who bring up Isaiah 53 – that the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53 is the nation of Israel, not a single individual. Levine and Brettler point out that in the earliest centuries, almost all Jewish interpreters read Isaiah 53 as about an individual, who may or may not have been believed to be the Messiah. Only after the Crusades (1096-1291), which greatly embittered Jews against Christians, did the standard interpretation of Isaiah 53 focus on the nation of Israel suffering for the sins of the world.

The book often presents flimsy explanations of Christian ideas, as if they arose from the speculative reading of a verse or two. Two lines in Genesis 1 are used to represent the Christian belief in the Holy Spirit and Trinity: “the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters,” (Genesis 1:2) and “Let us make mankind in our image.” (Genesis 1:26) While these verses are subject to multiple interpretations, a much wider network of scripture in fact underlies Christian theology about the Spirit, including the early Church’s experience of the outpouring at Pentecost. Deconstructed Bible verses never do justice to complex theologies, either Christian or Jewish.

Another issue I have is that the authors sometimes hide Jewish viewpoints that don’t fit their conclusions. On page 145 they stridently assert that “not a single text in the huge corpus of rabbinic Judaism suggests that after the Temple was destroyed, blood is essential to atonement”. But what they aren’t mentioning is that since before 700CE, a good fraction of observant Jews has practised kapparot on the eve of Yom Kippur, a ceremony where a person waves a chicken over his head and places his sins upon it. The chicken is then killed and the meat given to the poor. This is clearly an atonement sacrifice – kapparot means ‘atonements’ – but rabbinic scholars scorned the practice and didn’t write about it. The fact that the ceremony exists until this day reveals that sacrifice is seen as necessary for atonement by many Jews. Given the diversity of Jewish thought in The Bible With and Without Jesus, I was surprised that the authors couldn’t admit that this viewpoint does indeed exist.

Opening the lines of communication

Despite some weaknesses, The Bible With and Without Jesus includes a remarkable amount of interesting material about the ways Christians and Jews have interpreted the biblical texts, and the authors walk a difficult rope to find conclusions that will please both communities.

Christians should understand that the voices here are from secular academics who assume that the biblical text is an edited product of human understanding. But I applaud the authors’ desire to open the lines of communication between Christians and Jews.

The Bible With and Without Jesus by Amy-Jill Levine and Mark Brettler (HarperOne) is available now

No comments yet