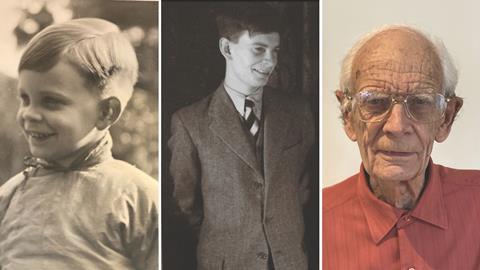

Basil Scott endured three “horrible” years inside a Japanese prisoner of war camp during the second world war. He explains how God later called him back to Asia, and why reconciliation is at the heart of the gospel

Basil Scott was only eleven years old on 15 August 1945, but it’s a day he still has strong memories of. “I remember it so vividly,” he tells me. “It was our liberation.”

Scott is recalling the jubilation of witnessing 40kg drums of food being dropped from US aircraft into the Japanese prison camp he’d lived in for the past three years. Tins of apricots and pears were a welcome sight after years of starvation. Fruit had never tasted so sweet, and neither had the hope that was finally realised on VJ day.

“Those three years were horrible, but I don’t regret them,” he says, recalling the painful separation from his parents which began when his boarding school came under Japanese rule in 1942. He witnessed Chinese locals being treated like animals by Japanese soldiers – scenes that still trouble him to this day.

“War made me the person I am. I saw how hope has the power to bring life. Hope is foundational – if you lose it, you lose love and faith as well. Many around me died because they lost their hope during war.”

Born to British missionary parents, Scott had moved to China in 1936, aged two, growing up within the old city walls and beautiful indoor courtyards of Lanzhong, western China.

Called to mission

After being released from prison camp in Pooting in August 1945, Scott finally made the long-awaited crossing of the Huangpu River to freedom in Shanghai, where he was reunited with his father. The family returned to Britain four months later.

While studying history and theology at the University of Cambridge, Scott longed for a personal commission into full-time ministry. He finally received his “marching orders from Christ” at the age of 21 – an experience he describes as “the most wonderful day of my life”.

“I was at the Cambridge Christian Union one Sunday in November 1955, and we were addressed by Billy Graham,” Scott recalls. “He spoke on sacrifice, and my question to God was: ‘Do you want me to give up my objection to being a missionary?’ The Lord’s ‘Yes’ was overwhelming.”

With a deep grasp of the scars which still divided Japan and China, his missional call back to Asia was in pursuit of peace and reconciliation, and a lifelong dialogue with Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus.

There is nothing more powerful than Christ to unite us

“Reconciliation is not a peripheral subject. It is the heart of the gospel,” Scott says. “Jesus came on a reconciliation mission to the world – and there is nothing more powerful than Christ to unite us.”

More than two decades after the end of the second world war, Scott met a Japanese PhD student, Minoru Kasai, who was also a Christian convert. It was a pivotal moment, as Scott began to grapple with his own personal capacity for reconciliation.

“I thought I had forgiven the Japanese until I met Minoru,” Scott admits. “But it wasn’t until we tried to pray together that I realised it was Christ alone who could unite us. Only once I was able to put the past behind me and look deep into his soul could we meet heart-to-heart. That was one of the most powerful moments of unity I’ve felt.”

Since this encounter, Scott firmly believes that mission begins and ends with prayer – and that deep connection, understanding and unity is at the heart of our Christian calling.

Healing

Despite the unimaginable ordeals of childhood, the British author and scholar, who has spent his career living and teaching in Asia, is still learning about the pursuit of peace, reconciliation and the powerful hope which kept him alive all those years ago.

A hip operation in April 2024 has recently cast his mind back eight decades, and Scott is once again digesting the scars and lessons of wartime, while unravelling a new understanding of mission from his home.

“I’m afraid I’m back to the skin and bone of 1944,” he smiles. “But although feeling helpless at times, I’ve been staggered by the care I’ve received.”

Now living in Leicestershire, he says he has been endlessly blessed by the largest community of Indians in Britain – constantly learning from their servanthood and humility. A small handful have been in and out of his home during a three-month recovery to treat an injury traced back to meningitis, which he contracted as a prisoner of war. Paralysed down his left side and unconscious for five days, Scott was cited as one of two miracle cases by the mission doctor who treated him as a ten-year-old.

“Back in 1944 it was a US Navy chap who performed ad hoc physiotherapy in our camp,” Scott laughs, recalling being carried around on the officer’s shoulder until finally regaining the use of his toes, legs and eventually walking again after six months.

“But today I’m moved by how my carers are doing jobs which, in their culture, would make them outcasts,” he says. “Men and women are coming into my bedroom and bathroom to clean me and help me move around – but they do it with such joy. It has encouraged me to a greater belief in humanity.”

Scott is grateful to be healing well, and is also grateful to be chosen by God to communicate a message of hope and unity in Christ to the people of Asia. Throughout his journey, he has pursued deep understanding of other faiths, following Christ’s path which, he says: “has carried me straight to where I am today”.

Made in God’s image

As he ponders the 80th anniversary of VJ Day, which takes place next year, Scott also reflects on a privileged missional life, preserved for the advancement of God’s kingdom.

“Mission is representing Christ and going with him to those with a completely different outlook,” he concludes, echoing his book God Has No Favourites (Primalogue Publishing). “Everybody is made in the image of God, so trying to see the world from their perspective is fundamental to communicating the gospel. Without loving and understanding others, we will never fulfil our commission or complete Christ’s work for us on earth.”

1 Reader's comment