Helen Naylor grew up thinking she was the daughter of two disabled parents, but a discovery in adulthood turned her world upside down

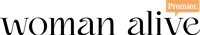

A strange sensation came over her as she stared at the family photograph at her grandparents’ home in Bristol. The image, which should have inspired warmth and a sense of belonging, left her feeling detached. “It was undeniable that I was my parents’ daughter since I shared their features, but I felt an otherness about me – even at four – of being an unwanted outsider in the intimacy of my family. And yet I can’t remember why I felt like that, only that I was already unhappy.”

These are the troubled thoughts that Helen Naylor (née Page) would recall decades later while writing her memoir: an attempt to piece together the puzzling parts of her life into one coherent story. Even as a child it was clear that she was missing a crucial part of the jigsaw.

CHILDHOOD CHALLENGES

“My parents were both diagnosed with disabilities when I was seven. My dad with a heart and lung problem… and then, at the same time, my mum was diagnosed with ME. But it was her illnesses that dominated our lives. Everything was about what she was able to do, what she wasn’t able to do, and the fact that she needed rest.”

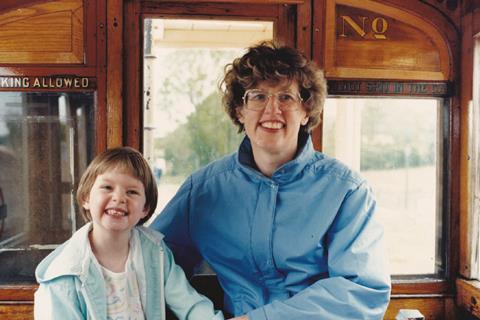

Elinor Page walked with a stick and would often complain about feeling unwell and needing to sleep. She spent every afternoon in bed and regularly reminded her daughter that no, she couldn’t walk with her to the corner shop. Sweetshop adventures, often the highlight of a child’s weekend, were one of many innocent pastimes crossed off the list during those precious years.

Helen’s father would go to the pub every day, leaving his young child home alone with her mother, who would retire to the bedroom, not to be disturbed. Years passed by with Helen creeping around the house, left to entertain herself. It was particularly challenging during the holidays, when the solace of school disappeared and the days stretched before her.

When Elinor was present, she would make subtle comments that undermined her daughter’s confidence: “She would tell me that I had fat fingers – not like hers, hers were perfect – and I had short, stubby legs – not like hers, hers were perfect. She would weigh me all the time.”

Long periods spent alone, combined with the verbal abuse she suffered, left Helen increasingly depressed. Perhaps the persistent feeling that something was wrong was because there was something wrong with her? After all, that’s what her mum kept telling her.

When Helen was 16, her parents announced they were going on a “once-in-a-lifetime trip” to America to visit family. Her relatively sheltered life was suddenly infused with possibility.

The Pages spent a glorious fortnight sightseeing and eating out. The most incredible part of it all was that Elinor was well. Gone was the stick, the afternoon bedrest, lethargy and pain. Both parents were available and energised, walking everywhere and interested in everything. To anyone looking on, this was a normal, happy family on vacation.

But “the moment we got back to the airport,” says Helen, “it was back to wheelchairs and sticks and disabled badges…I just accepted that now we were back to previous normality…

“I was really confused why we didn’t just pack up and move to America, because America had made them better.”

While the US had not cured Elinor, as she had told her daughter, something shifted in Helen, and during the years that followed, questions began to form in Helen’s mind. It wasn’t until her mother’s death, 17 years later, that she finally discovered the truth.

SECRETS AND LIES

Elinor died in 2016, and in the months after, Helen began to read the diaries her mum had kept since childhood. “I found out that she had physically abused me as a child. Before I was school age she had drugged me, she’d left me to go to the shops when I was a baby, she’d fed me Chinese food washed down with whisky, she had broken my arm at one point, and there’s lots of injuries that go unexplained.”

She also discovered that, during the time Elinor had been saying ME was preventing her from walking to the corner shop, she had been organising city trips and going apple picking while Helen was at school. Slowly, Helen began to realise that everything her mum had ever told her was a lie: “I’m pretty certain she had narcissistic personality disorder…and because I was a child she was able to manipulate me completely, because you do trust your parents, and you trust them for your sense of truth and identity.

Because I was a child she was able to the content you love manipulate me completely

“She went to Birmingham for three months in the last year of her life and they tested her for literally everything – including unusual versions of Parkinson’s. They tested her brain, her stomach, literally everything and they say they came up with nothing.”

Elinor may not have been living with a chronic disease, but Helen has come to believe that she was, in fact, suffering from Munchausen’s syndrome – a psychological disorder that leads to a person faking, or inducing, illness in order to gain attention from others.

CLARITY IN CHAOS

Reflecting on the pain Elinor caused her, Helen says: “As I was growing up I really believed that there was something wrong with me. I felt that I was unlovable, that I was a burden to everyone around me. I grew up feeling completely unworthy of anything.

“I think the gaslighting [manipulating someone into doubting their own sanity] was really destructive, because it makes you really doubt everything you know. You feel like you’re a stranger in your own body, a stranger in your own mind, so that meant there was no safety at all in my childhood and, as I was growing up…I couldn’t work out who I was; I had no basis to do that.”

Everything Helen thought she knew had been false. Everything, that is, apart from her faith: “God works in amazing ways, right? And he can use that situation. And you know, she did tell me some real truths – whether she understood them or not, I don’t know.”

Elinor’s faith is one of the many conundrums that Helen still grapples with today. Her mum went to church and Bible classes, shared the message of Jesus with her when she was seven, and yet led a deeply duplicitous life that had huge ramifications for her daughter, who is still in therapy, aged 39. Was her faith genuine? Helen wonders whether her mother simply craved a captive audience to listen to her woes.

As for Helen, she says she had “a really close relationship with God” that blossomed into a deep dependence. In the years before Elinor died, when she was struggling with her mother’s destructive behaviour, God began to speak to Helen in “dreams and visions”, warning her to walk away from the relationship.

Helen credits God for pulling her through many of her darkest moments: “At age 16 I felt like I had nothing to live for, I had no future and I was totally worthless. I look at my life now and I have an amazing family, I have amazing friends, I’ve published a book, which has been my dream forever and, I would say, all because of God. I know that a lot of people with this kind of abusive background and really difficult childhoods can suffer with alcoholism and go down really difficult roads; drug addictions and so forth. My life could have looked really different…”

The clarity and peace God has brought Helen is something she was keen to share in the pages of her memoir: “I think it’s amazing, because then God is able to use my story. I’ve had so many people contact me and say: ‘Oh my goodness, you’ve just explained my life to me.’”

Helen Naylor’s memoir, My Mother, Munchausen’s and Me (Thread), is out now