The histories aren’t told of the tens of thousands of slaves who became Christians in the Caribbean, or the black people who fought to end slavery. When some stories are celebrated and others repressed, it affects our present more than we realise, says Calvin T Samuel

Since 1987, October has been celebrated in the United Kingdom as Black History Month. It’s an international and intentional attempt to engage with black history in recognition of the reality that history is usually written by the powerful. This means that some strands of history are overlooked or suppressed.

Black History Month is an attempt to uncover and recover that overlooked or suppressed history, which is our shared history.

Connected

Whatever our ethnicity, we have an interconnected history, not least because of the global nature of the British empire. For us Brits in particular, our history is profoundly intertwined across African, Asian and European people groups. In his brilliant book, Black and British: A Forgotten History (Pan Macmillan), David Olusoga makes that very point.

However, the British empire was hardly the first empire to integrate peoples from across those continents. The Roman empire did the same. So there have been people of African descent living in Britain since Roman times including, most famously, ‘the ivory bangle lady’, whose remains, which date back to the fourth century, were discovered in York.

A selective history

That black history attempts to recover history that has been forgotten or suppressed is important because the choices made about whose histories are privileged or forgotten also determine, consciously and unconsciously, how people are perceived and categorised in the present.

By way of example, as someone who grew up in Antigua, the history that has been privileged has been that of the British empire. So we Antiguans are proud of the fact that, before Nelson became the hero of Trafalgar, he learned his trade in Antigua, where he was deployed in what is now known as Nelson’s Dockyard for three years.

The choices made about whose histories are privileged or forgotten determine how people are perceived in the present

It’s well documented how the island was taken from the indigenous Caribs, initially as a Spanish colony in the 1490s, and then taken over by British settlers from the neighbouring island of St Kitts in the 1630s.

As a Methodist, I’m happy to tell of the amazing fact that the first Methodist congregation in the world planted outside the British Isles was in Antigua in the 1760s.

Forgotten stories

In the histories that are typically remembered, the heroes were white, British and usually male.

In contrast, the histories that are forgotten or supressed include the histories of the indigenous Caribs, after whom the Caribbean is named, who had lived on the island for 500 years, none of whom survived their encounter with British settlers.

Nor are the histories preserved of the Africans who survived the tortuous middle passage, shipped from Africa to the Caribbean to replace the Caribs wiped out by genocide.

The histories aren’t told of the tens of thousands of slaves who became Christians in the Methodist Church, constituting the vast majority of the membership of the new denomination spreading across the Caribbean.

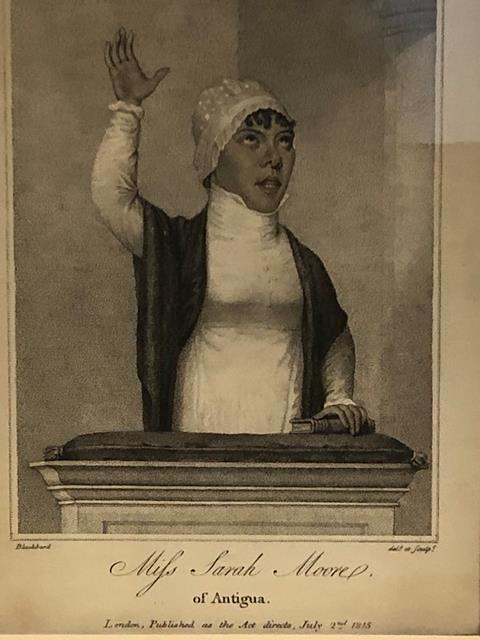

The National Portrait Gallery boasts 32 portraits of Wilberforce but only four of black abolitionists of the same era

Histories of the enslaved labour underpinning the wealth created in colonies like Antigua by the production of sugar or cotton in the 17- 19th centuries, upon which Britain’s economic and political power were built, are still suppressed today.

Those histories are forgotten, quite often because they are unpalatable. Instead, we tell alternative stories to soften the ugliness of the racist structures so deeply embedded in our shared history.

For example, we tell the story of William Wilberforce and his lifelong fight for abolition, a feel-good story for us Brits which reinforces our values of fair play and justice. In so doing, we conveniently ignore the fact that the fight for abolition was necessary only because the British empire was wholly committed to and built upon slavery for centuries.

Moreover, while the National Portrait Gallery boasts 32 portraits of Wilberforce, it has only four portraits of black abolitionists of the same era. Here is a visual representation of the histories we don’t tell of the efforts of black people to free themselves; both the slaves who revolted and fought for their freedom in the colonies, and the black abolitionists who advocated for them here in Britain, such as Mary Prince, the first black woman to publish her life story.

As Christians committed to justice, black history matters because it’s our shared history

Correcting the course

This privileging of European perspective, the so-called ”white framing of history”, is what Black History Month attempts to expose and to reframe. It provides, for example, opportunity to reflect on why it is that we’ve heard much about Florence Nightingale but little of Jamaican, Mary Seacole, who served in Crimea at the same time.

Christians should care about Black History Month because it is an invitation to recover a forgotten and supressed history which offers us a better understanding of the world, its people, and ourselves. As people committed to justice and who are followers of the one who is the truth that sets us free (John 8:31), I suggest that black history matters to us all because it’s our shared history.

My prayer is that a day will come, and soon, when our divisions are truly overcome and our histories are genuinely shared.

So I’m delighted that during Black History Month, Premier Christianity will be sharing further black stories. May this month be a time of curiosity and sharing, conversations and celebrations, challenge and encouragement. Amen.