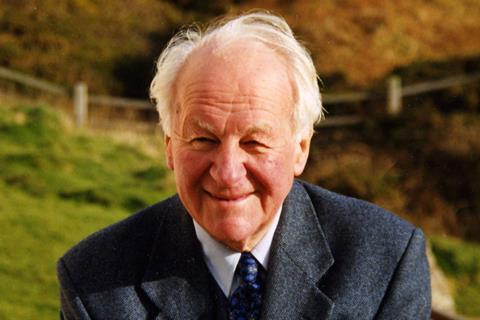

John Stott, once named among of the 100 most influential people in the world, possessed a borderless influence that shaped the global evangelical movement. Ahead of Stott’s birthday (27 April) Dr Donald Sweeting honours his dear friend’s life

In the history of modern evangelicalism, few names shine as brightly as John Stott’s.

TIME magazine named him one of the world’s 100 most influential people in 2005. Described as the “theological leader of world evangelicalism” by biographer John Pollock, Stott combined intellectual rigor, pastoral warmth and an unwavering commitment to the gospel. Over his remarkable life, he shaped not only the Church of England but the entire global evangelical movement, leaving a legacy that continues to bear fruit today.

Stott’s influence spanned continents, generations and fields of ministry. As someone privileged to have known him for 35 years, I witnessed firsthand his passion for Jesus, his love for people and his unrelenting desire to see the Church thrive. He was not only a man of extraordinary gifts but also of extraordinary humility — a rare combination that made his life all the more compelling.

A meek man before God

Born in 1921 into a prominent London family, Stott grew up with many privileges that God would later use to prepare him for ministry. His father, Sir Arnold Stott, was a distinguished physician and a cardiologist to the royal household. The family’s home on Harley Street, in London’s prestigious medical district, was filled with servants and nannies. Despite this comfortable upbringing, Stott often felt spiritually isolated. It was at Rugby School, under the influence of a chaplain named Eric Nash, that his life took a decisive turn. Stott’s encounter with Christ as a teenager gave him a vibrant faith and a clear sense of calling, even as it strained his relationship with his father, who hoped his son would pursue a career in diplomacy.

Stott went on to study at Cambridge University, earning a first-class degree in languages and theology. During these years, he developed the disciplines and intellectual habits that would mark his entire life. It was also at Cambridge that he began to take leadership roles in Christian ministry, serving with the Cambridge Intercollegiate Christian Union. By the time he graduated, Stott knew he was called to pastoral ministry. In 1945, at the age of 24, he was ordained in the Church of England and returned to his boyhood church, All Souls, Langham Place, where he would eventually become rector.

Those who worked closely with him often called him “Uncle John,” a title that reflected both the affection and respect he magnetised.

At All Souls, Stott’s ministry took root. The church, located in the bustling heart of London, became a hub of vibrant evangelical life under his leadership. Stott believed deeply in the power of prayer, the necessity of expository preaching and the strategic importance of training leaders. These became the hallmarks of his ministry. “Without prayer,” he once said, “neither we nor the people we serve will become Christlike.”

This conviction was not just rhetoric; it was evident in his daily life. Before every sermon, Stott would kneel at his platform seat, visibly surrendering his message to God.

His expository preaching was equally transformative. With clarity and depth, he unpacked scripture, guiding his congregation through books of the Bible with a combination of theological insight and pastoral application.

Stott’s impact was not confined to London. By the 1960s, he had become an international figure in student evangelism. Traveling to university campuses around the world, he demonstrated that evangelical Christianity could be both devout and intellectually credible.

His missions at Cambridge, Oxford, and Urbana influenced thousands of students, showing them that faith and reason were not enemies but allies. For Stott, the university was a mission field of critical importance. It was there, on campus, where he mentored young leaders, many of whom would go on to have significant ministries of their own. Those who worked closely with him often called him “Uncle John,” a title that reflected both the affection and respect he magnetised.

His study assistants, tasked with everything from research to driving him to appointments, were often struck by his discipline, humility and kindness. “We were treated to a master class in how the Christian life ought to be lived,” one of them recalled.

Borderless influence

Beyond his personal mentoring, Stott was a prolific writer. He authored more than 50 books, translated into 65 languages, making his influence truly global. His works, including Basic Christianity and The Cross of Christ, remain foundational texts for evangelicals.

His writing was not merely academic though — it was pastoral, designed to equip believers for ministry and mission. In 1971, he founded the Evangelical Literature Trust, using the royalties from his books to provide theological resources for pastors in the Majority World. Stott often said, “You cannot preach if you do not study, and you cannot study if you do not have books.”

His commitment to making biblical resources accessible was a reflection of his broader vision for the global Church. This vision was perhaps most clearly embodied in the Langham Partnership, a ministry he founded to equip leaders in the Majority World. Recognising the explosive growth of Christianity in regions like Africa, Asia and Latin America, Stott sought to ensure that this growth would be accompanied by theological depth and strong leadership.

The Langham Partnership provides scholarships for pastors to pursue advanced theological training, offers biblical preaching workshops and distributes evangelical literature. Stott’s vision was that every church in the world would be served by a pastor who “sincerely believes, diligently studies, faithfully expounds, and relevantly applies the Word of God.” To date, the Langham Partnership has equipped hundreds of leaders, ensuring that the global Church continues to grow in both size and maturity.

Christian duty and social responsibility

One of Stott’s most significant contributions to global evangelicalism was his leadership in the Lausanne Movement. As the chief architect of the 1974 Lausanne Covenant, he helped articulate a vision of mission that integrated evangelism with social responsibility. For Stott, the gospel addressed not only spiritual needs but also societal ones. “Although reconciliation with man is not reconciliation with God,” he wrote, “nor is social action evangelism, nevertheless we affirm that evangelism and socio-political involvement are both part of our Christian duty.” This holistic understanding of mission challenged the evangelical world to engage more deeply with issues of justice and mercy.

His life serves as a reminder of the power of a life wholly devoted to Christ

Stott’s ability to navigate complex theological and cultural debates was a testament to his wisdom and grace. Whether addressing disagreements within the Lausanne Movement or engaging with critics, he remained committed to unity and truth.

His friendships, which spanned theological, cultural and national boundaries, were another hallmark of his ministry. Stott had a remarkable ability to connect with people, whether they were world leaders, young students or fellow pastors. His humility and genuine care for others left a lasting impression on all who knew him.

My dear friend

As I reflect on Stott’s life, I am struck by the breadth of his influence and the depth of his character. He was a man of remarkable gifts — an evangelist, theologian, pastor and friend — but what stood out most was his humility. He once summarised his priorities simply: “students and pastors.” For him, the work of equipping the next generation of leaders was not a task but a calling.

In one of my final visits with Stott, I read him a letter thanking him for the ways he had impacted my life. I listed seven things: his example of faithfulness, his clear articulation of evangelical truth, his global vision, his ministry of writing, his commitment to preaching, his thoughtful approach to Christianity and his dedication to mentoring younger leaders. When I finished, he looked at me with a twinkle in his eye and said, “What about friendship?” Indeed, his capacity for friendship was one of his greatest gifts, and it multiplied his ministry in ways that only eternity will fully reveal.

John Stott’s life was a living example of Eugene Peterson’s phrase, “a long obedience in the same direction.” His legacy is a call to all of us to remain faithful in the work of building God’s Kingdom, whether through preaching, writing, mentoring or living out the gospel in every area of life. For the wider Church, his life serves as a reminder of the power of a life wholly devoted to Christ.

Listen to The Bible for today with John Stott on premier.plus/johnstott

No comments yet