The stabbing of the author of The Satanic Verses and an old college photo of assassinated Pakistani Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto, reminds George Pitcher that living self-sacrificially is a key tenet of the Christian faith

I wrote a short script last week for a BBC Radio 2 slot that I do irregularly. The spot, Pause for Thought, is an exercise in applied theology; we’re given a theme which we examine through the context of our faiths.

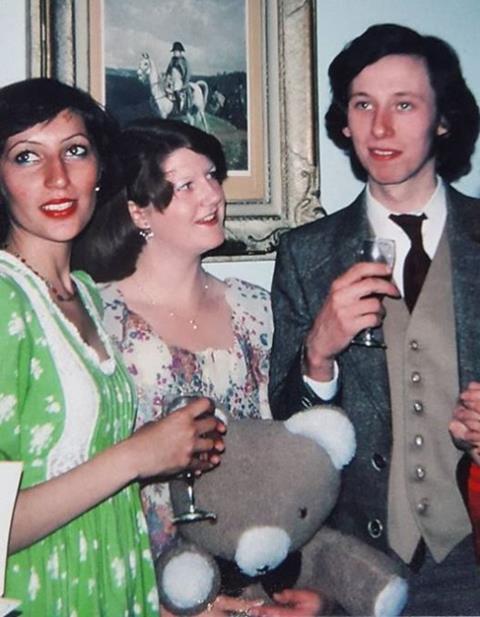

The theme was ‘my favourite photograph’ and I chose the screensaver on my mobile phone. It was taken in the spring of 1976 and shows a big-haired, 20-year-old me at my friend Paddy’s 21st birthday bash in his Oxford college, next to two young women. One is standing under a portrait of Napolean on his horse and holding a giant teddy bear; the other is a young Pakistani woman. I and this young woman are looking away at something in the near distance – a home movie screen, showing images of the school days I shared with Paddy.

Can it really be sufficient to applaud those who risk everything without finding some substantive way to stand alongside them?

I’m post-rationalising it now, but she looks as if she’s gazing purposefully into the future. For this was Benazir Bhutto, who later went on to be the great reforming prime minister of Pakistan in the late 80s and 90s. None of us there – including her I believe – could have guessed that then. My friend Paddy had probably just introduced us with something like: “This is Benazir – her family are quite big in Pakistan.”

Common ground

My family say I have this screensaver because it’s an image of a callow me with a future famous stateswoman. My script for the BBC tried to mount an argument, perhaps a little portentously, that I keep it because every time I pick up my phone, it reminds me what it is to live a life self-sacrificially.

Culturally and socio-economically, Benazir and I were very different. But in our faiths (she a Muslim; me developing a Christian curiosity) we shared more in common regarding the primacy of a self-sacrificial life than divided us. Benazir fought tirelessly for woman’s rights and liberal democracy in Pakistan before being assassinated in Rawalpindi in 2007, aged 54. By contrast, I went on to the safety and self-indulgence of UK journalism. Each to their own, I suppose.

Since I drafted that BBC script, the author Salman Rushdie has been stabbed and severely wounded at an event in New York. The attack reminds me that the world has got less safe since I met Benazir. The precious tenets of liberal democracy for which she fought - such as the freedom of speech and religious expression – are more threatened than we could have imagined at a party in the mid-70s.

Risking everything

I wonder now whether it’s a sufficiency to acclaim a life led self-sacrificially. To be sure, it’s a founding principle of the Christian faith, if we aspire to be Christ-like in the model of the Nazarene. But in the face of religious intolerance, fundamentalism and, indeed, fascism, can it really be sufficient to applaud those who risk everything to live by what they believe in, without finding some substantive way to stand alongside them in solidarity?

Benazir was a moderniser, a democrat and a fierce defender of human rights. She believed that the future of Islam depended on embracing such secular values. But there are also mild accusations of hypocrisy levelled at her. According to her biographer, Shyam Bhatia, she was “chameleon-like” and “prepared to be all things to all people”. She presented as a conservative Muslim in Pakistan and as a social liberal in the West. We’re holding wine glasses in our photo – mine was certainly filled with wine and I think hers was too. Viewed positively, this was surely a talent for meeting people where they are, rather than where we demand them to be.

Until we can show that we’re in this together, we can’t call ourselves sisters and brothers

According to the CIA, Benazir’s murder was almost certainly orchestrated by the Pakistani Taliban. Rushdie’s attempted murder, some 15 years later, was apparently at the hands of a lone terrorist, carrying the authority of the Fatwa served on him by the Ayatollah of Iran in 1989 for the alleged blasphemies of his novel The Satanic Verses. Today’s Iranian government blames the attack on Rushdie himself and his supporters.

Standing together

Both Benazir and Rushdie are viewed as apostates by elements of fundamentalist Islam. The former maintained her Muslim faith, the latter renounced his for a “hardline” (his word) atheism. What they share is a belief in equality of freedom of thought and expression for believers and non-believers alike.

As far as my tribe is concerned, the Anglican Communion recently concluded its decennial Lambeth Conference, having invested most of its attention on what consenting adults of the same sex may or may not do in the privacy of their bedrooms. That is clearly no longer good enough. History shows us that wrung hands are deeply insufficient. The Christian West needs to stand firmly and demonstrably in the corner of both Muslims like Benazir, and atheists like Rushdie.

Until we can show that we’re in this together, we can’t call ourselves what we should be – their sisters and brothers. Worse, we can’t call ourselves witnesses to the living Christ.