The Levelling Up secretary recently said the government can’t help everyone struggling with the cost of living crisis. Rev George Pitcher asks: why not?

I went to our local Church of England primary school last Monday morning for its assembly, which is really an act of collective worship, and one of the more pleasurable duties of a parish priest that was rudely disrupted by the pandemic.

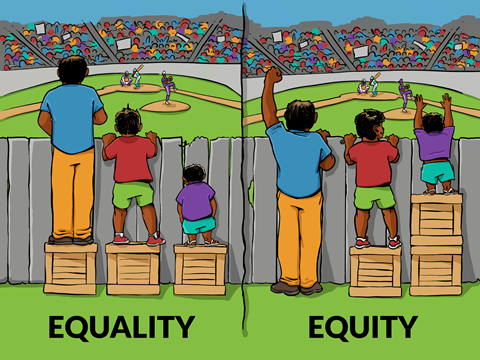

The deputy head was exploring the theme of justice, fairness and equality - and the difference between them. One of her slides (which I was touched to see included translations for the five new Ukrainian children present) featured a cartoon of three boys, each standing on a box to try to watch a baseball game over a fence (I expect the Ukrainian children are just as bewildered by cricket).

The tall boy could see, the middle boy could only just see and the small boy couldn’t see over the fence at all. The next frame had the boxes redistributed so all three boys could see over the fence. This illustrates for children the difference between equality versus equity.

It’s also the kind of thing that gets increasingly shouty right-wing broadcasters to accuse the Church of being a seething vipers’ nest of lefties. Because it also seems to illustrate the great Marxist dictum: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

Jesus of Nazareth points to a God whose unconditional grace is, as it were, a universal credit

That brief summation of the Communist Manifesto comes to mind because another great leveller-up of the proletariat, cabinet minister Michael Gove, let it be known at a business summit last week that “we can’t help everyone with the cost of living”.

That was the headline anyway. What he said was actually a little more nuanced: “It is inevitably the case [that]…you cannot do all things you would, in ideal circumstances, in order to support people through a difficult period.”

So who is the everyone that Gove’s government can’t help with the cost of living crisis? He may not need to help the wealthy, though it would be a Conservative instinct to do so (witness the continuing push for tax cuts from the right of his party). It must be elements of the less wealthy and the poor that Gove and his colleagues can’t help.

This inevitably focusses attention, as it always does at times of economic crisis and recession, on the putative difference between the deserving and the undeserving poor, a distinction that Gove and his colleagues are invariably keen to make under these circumstances.

There’s usually a nod to the Victorian era here too, supposedly a golden age during which the well-to-do distinguished between the deserving and the undeserving, before the welfare state messed everything up, giving us today (the argument goes) an underclass of lazy fatties, smoking fags and boozing in front of widescreen HD tellies at the expense of the hard-working taxpayer.

I’m not sure how they would manage that, with a packet of twenty now costing well over a tenner, but there you go. This stereotype is probably apocryphal. It’s also useful, because it neatly avoids far more typically visible cases of deprivation, such as single parents struggling to hold down two underpaid jobs to feed children, against the highest rates of price-inflation for three decades.

Rich in faith

The “undeserving” are not delineated in our gospel. The poor – and these are not just the economically poor, but the marginalised, the sick, the despised and the alien – are as deserving of salvation as God’s supposed “chosen”.

Jesus of Nazareth points to a God whose unconditional grace is, as it were, a universal credit. “Your faith has made you whole” (Mark 5:33-34) offers the doctrine on which the Reformation was fought many centuries later across Europe. No demarcation here between ‘strivers and shirkers’, the beloved pantomime characters of Tory politicians.

The Protestant work ethic, coined by the German sociologist Max Weber, has been redefined over more than a century as a consequence of faith rather than a cause of it. It’s also why the new perspectives on St Paul’s epistles have removed the idea that classical theology was based on the ancients’ ideas of “good works” finding favour with the Almighty (though there is still some of that in the prosperity gospels in the US) and only overturned by Martin Luther at the Reformation. More common now is the far more radical idea that God’s grace has been vouchsafed as unconditional since the time of Augustine.

Since the nineteenth century, the direction of travel has been towards a liberal Catholic social gospel, to which the Church of Rome had borne witness in response to its earlier corruptions, which gave us the Reformation. All of which serves to demonstrate in part that it is the Christian nation’s duty to serve the poor, rather than the poor’s burden to deserve it. It is, to coin a phrase, an inconvenient truth, but few have pretended that the gospel is not uncomfortable and without scandal.

The privileged few

At a more secular level, the American political philosopher Michael Sandel, in his book The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good (Penguin Books), argues that the principle of meritocracy is toxic. It tends to give those in positions of power and wealth the impression that they have risen there through their own virtues (diligence, hard work, talent and so on). And so they are entitled to their privilege.

It follows in this social psychology that the poor have failed to prevail through lack of such virtues. It may serve to explain why we still persist in the UK in separating the wheat from the chaff in our children at age eleven with the eleven-plus examinations. The sooner we separate the deserving from the undeserving the better, right?

There’s more than a little of this in Michael Gove’s throwaway (in every sense) phrase that not everyone can be helped. The gospel tells us that the poor are always with us (Matthew 26: 11), but scripture also tells us the imperative is to serve them.

So Gove may be right that we can’t help everyone, but that doesn’t mean he or we should give up trying. If it means anything at all, isn’t that what levelling-up is all about?