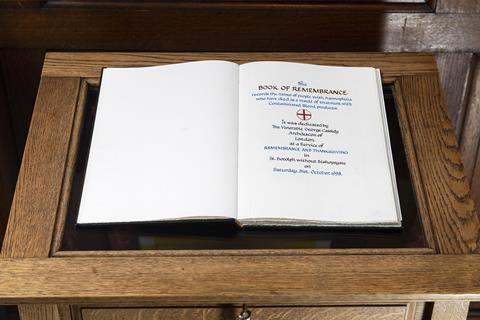

St Botolph’s church is home to the national memorial for those who have died as a result of receiving infected blood products. Fr David Armstrong explains what the conclusion of the inquiry means to those who have been waiting so long for justice

Sir Brian Langstaff’s report into the infected blood products scandal may have marked the end of his inquiry, but it is far from the end of the issue for those who are infected or affected. The report is exemplary in its integrity and insightfulness, yet the question still remains: why must it be so difficult, and take so long, to obtain justice in the UK?

Remembering

At St Botolph’s church, each year we hold a service of thanksgiving and remembrance for those who have died as a result of receiving contaminated blood products. This is the most poignant, and I would say the most moving, annual service we hold here - and there are very many services in the church each year.

![]()

The community of those who gather for the memorial service (and others we hold in conjunction with the Haemophilia Society) is eclectic, but strongly united in the desire for truth and justice.

Each one of them has their own personal feelings about what has happened, what is happening, and how they and their loved ones have been treated.

It has been – and still is - an emotional rollercoaster on which the pain of loss and frustration does not lessen. Part of that has been caused by successive Governments’ action and inaction. In this public inquiry, the arguments and counterarguments have added to the associated anxiety of waiting.

The publication of Sir Brian’s report brings vindication for those affected, but it does not lessen the impact of decades of procrastination, government lies and being ignored.

The road to justice

Under the stewardship of Sir Brian, confidence in the inquiry grew. He exhibited a fearless determination to achieve recognition of past wrongs. His empathy, belief in real-life experience and appreciation that people are central to the inquiry have helped pave the road to justice.

The issue of compensation payments is now on the agenda and, with it, comes an enormous surge of emotions. What is the price of a life?

Each year we hold a service of thanksgiving and remembrance for those who have died

It will inevitably be divisive and accompanied by feelings of discomfort, grief, guilt and relief; relief in recognition, but guilt that other people have not received compensation, or yet others will not be included in the compensation system at this time.

We all know, in our hearts, what is right. We each have an innate feeling of fairness. At St Botolph’s, we are praying that any who feel left out and excluded in the infected and affected community will soon find a proper sense of just recognition, fairness and unity.

Finding a new path

For nearly six years, the inquiry has been a constant in many people’s lives. It has nurtured a real-life and online community of people. Inevitably, the legal acknowledgement, and the publication of the findings, will have a psychological impact on many. It may even create a void of sorts.

The community itself will soon see dramatic change. While there is still a sense of waiting in limbo as final decisions and outcomes are decided, the end is now in sight.

What is the price of a life?

Throughout the years of obfuscation, the community of those infected and affected has maintained grace and magnanimity beyond measure. The dignity with which they have acted, and that they displayed at the publication of the report, is testament to their strength and unity as much as to their need, rightly so, of justice.

As political campaigning gathers momentum in the run up to the general election in July, perhaps, among all of the verbal argy-bargy that we see, we could simply have a promise from politicians to work with honesty and integrity.

An honesty and integrity which reflects the dignity and good grace of those who have waited, and are waiting, so long for justice in the UK.

1 Reader's comment