The chair of Christians in Media says journalists are entitled to breach ethical guidelines in cases of overwhelming public interest

It was alleged that the 18th century Irish MP, Edmund Burke, once stood up in the House of Commons and said, “There were three Estates in Parliament, but, in the reporters’ gallery yonder, there sat a Fourth Estate more important than they all.”

Burke’s old-fashioned language affirmed the new role of journalists to hold those in power to account; to call out injustice; to be a voice for the voiceless in a class-ridden world where decisions were made by an elite, ruling class often behind closed doors.

Today, these same principles still apply and, I contend, are even more crucial in an era of a hugely diverse media, and multiple channels of communication.

When writing a story, journalists must consider both legal and ethical issues. Laws are in place to restrict journalists from reporting things which may damage or harm other people or organisations. Good journalists will double-check their sources; give those criticised a right of reply; respect people’s privacy; protect the vulnerable to name just a few.

We should not rush to judgement and seek to blame Ms Oakeshott or ‘the media.’

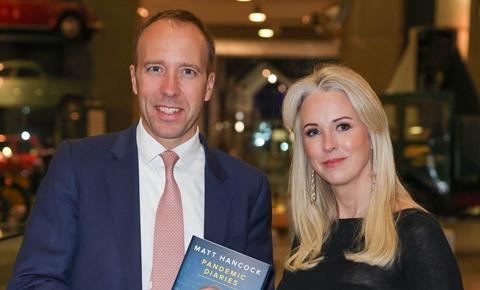

These ethics have been brought under the spotlight with the collection of some 100,000 WhatsApp messages sent between the then Secretary of Health, Matt Hancock, and other ministers during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic that have been obtained by The Telegraph.

The journalist at the centre of the story, Isabel Oakeshott, has been roundly criticised for breaking a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) in making these messages public.

Yet, journalists are entitled to breach their legal and ethical guidelines in cases of overwhelming public interest – one that is considered to be a strong ethical principle in its own right. Ms Oakeshott’s decision to go public is based upon the detection of serious impropriety, highlighting the need to protect public health and safety, and the appearance of the public being misled by the actions of those in power.

God requires every Christian to have integrity and a pure heart in their daily lives. So, it’s not surprising that many Christians find Ms Oakeshott’s actions very difficult to understand or, at worst, extremely disagreeable. Yet, at a time when so many of us were struggling with the loss of loved ones, unable to give comfort in those last moments, it is also disheartening to learn of the apparent lack of sensitivity by some in positions of power. Integrity and truth apply to all people whether they are journalists or politicians.

We should not rush to judgement and seek to blame Ms Oakeshott or ‘the media.’ Instead we should remember that behind the abstract notion of media lie many Christian men and women, who are seeking to glorify God in a very challenging public space.

At Christians in Media, we will always uphold the role of the media, and journalism especially, to challenge the status quo, the political establishment and shine a bright light of truth and integrity on those dark areas of decision-making that affect our daily lives. Ms Oakeshott’s choice to make public some of the exchange of messages between Mr Hancock and ministers is one example of bringing to light information that affects you and me. Paradoxically, it also challenges our desire to stand for honesty, integrity and biblical truth that motivate our very mission purpose, and who we are.

Our instinctive response is to point the finger at Ms. Oakeshott for breaking a confidence. However, there are times when it is right to take a step back, and look deeper into a story for the hidden truth; that not all matters of contention are so easily explained.

Jesus notoriously challenged the political and religious leaders of the time. In keeping with the prevailing Rabbinic methods of discourse and debate, Jesus responded to the chief priests, teachers and elders questions with a question of his own – one that proved too humiliating for the would be detractors. In true journalistic style, Jesus challenged the status quo and was able to reveal a fear of losing face, losing power. He did not reveal the source of his authority, but shone a light upon the motives and actions upon others.

2 Readers' comments