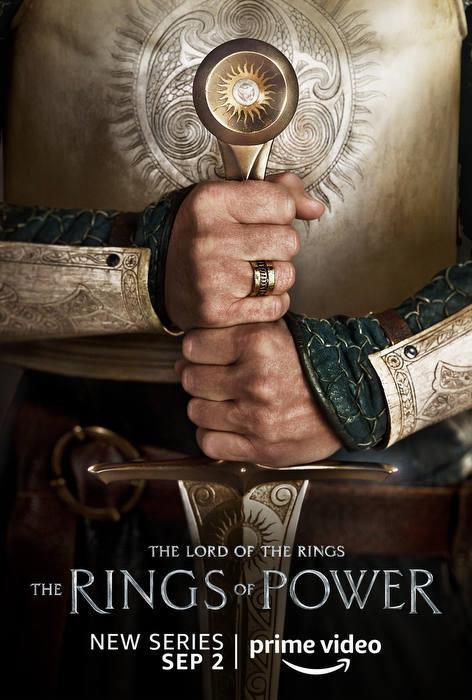

Reported to cost more than £350 million, Amazon’s new series Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power is the most expensive TV series ever created. Giles Gough takes a look at how J.R.R Tolkien’s Catholic faith shaped one of the best-selling books of all time

When compared to fellow writer C.S. Lewis, J.R.R Tolkien is commonly thought of as more acceptable in secular circles. But while Tolkien did not foreground his Christianity in his work, it would be a mistake to say that it’s not there.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s father died when he was just three and his mother, Mabel, died when he was twelve. A devoted Catholic, Mabel entrusted the care of her two boys to a local priest, who helped to strengthen the seeds of faith planted by their mother. When he was 16, Tolkien met Mary, a fellow orphan, and the two promptly fell in love. Mary converted to Catholicism before they married, which gives us a good idea of how seriously he took his faith.

Tolkien was quite open about his beliefs when asked, but this didn’t translate automatically to his collected writings on middle-earth, which was intentional; Tolkien couldn’t stand allegory. As he stated in the foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings: “I cordially dislike allegory…I much prefer history – true or feigned – with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.”

So it’s applicability, not allegory, that Tolkien is interested in. An author telling a reader that “this equals that” is too restrictive for him. He wants the reader to ask: “Could this mean that?” This is an absolute gift for literary critics, as it gives us the green light to apply different lenses to the text (and frankly, we were going to do that anyway). With that in mind, let’s apply a Christian lens to The Lord of the Rings and see if we can find a few faith parallels you might have missed.

An easy comparison

This is the low hanging fruit of gospel parallels, and as most of you will have figured this one out on your own, we’ll dispense with it pretty quickly. Gandalf fights the Balrog in the mines of Moria in Fellowship of the Rings. He defeats the fearsome monster, but not without being dragged down with it. With the parting words: “Fly, you fools!” Gandalf the Grey sacrifices his life for his friends.

The comparison to the resurrected Jesus is so huge it could be seen from outer space

Their grief is intense but short-lived as he is resurrected soon after. Returning with even more power (and the kind of glow-up the Queer Eye team would be proud of) Gandalf the White re-joins his comrades. He’s resplendent in white robes, and the comparison to the resurrected Jesus appearing to Mary Magdalene is so huge it could be seen from outer space.

A heavy burden

While many compare the destructive power of the ring to the atom bomb, it’s not difficult to see it as a metaphor for sin. Sauron is evil incarnate and he effectively tricks men, elves and dwarves into wearing these rings, leading (for the most part) to their corruption and death. One could draw comparisons between the way sin transforms and kills people to how the ring transforms Smeagol into Gollum and ultimately destroys him.

But what’s more compelling to think about is Frodo taking on the job of destroying the ring, which could have parallels with Jesus taking on the task of saving mankind.

In the film, when Frodo volunteers to take the ring at the council of Elrond, we see the sadness and compassion writ large on Gandalf’s face. If one were to imagine the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit all discussing what’s to be done to save humanity, and the moment in which Jesus volunteered to take on the sins of the world, it’s not much of a stretch to imagine that God the Father’s face might echo Ian McKellen’s expression in that moment.

A rejected heir

Frodo meets Aragorn on his travels; a mysterious wanderer who is revealed to be heir to the throne of Gondor. For centuries, Gondor is a kingdom that has been without a royal line and instead ruled by the stewards, a line of chief advisers who watch over it until the true king returns. However Denethor, the current steward, flat out denies Aragorn’s claim: “Even were his claim proved to me, still he comes but of the line of Isildur. I will not bow to such a one, last of a ragged house long bereft of lordship and dignity”.

With this comparison in mind, it’s easy to see Denethor as a figure like Caiaphas, the high priest who presided over Jesus’ trial. It’s been prophesied that a king will come from the house of David, but David, like Isildur, was a king who gave into temptation with ruinous results, and Jesus comes from the scruffy town of Nazareth. So both Caiaphas and Denethor deny the claims of this servant-king with humble roots.

Wounded for us all

Quite early in Fellowship, Frodo is stabbed by the witch-king at Weathertop. He would have died then and there if it wasn’t for the intervention of the elves, leading to his recuperation at Rivendell. Frodo is able to endure the perilous journey and, with Sam’s help, sees the ring’s destruction. But the wounds he suffered never really healed. “I have been too deeply hurt”, Frodo tells Sam before he leaves with the elves and Gandalf for the Undying Lands (a fairly clear analogy for heaven).

Although they saved middle-earth, Frodo paid a permanent price for it. It wouldn’t be hard to compare this to Jesus, and how even his resurrected body bore the wounds of crucifixion. As Jesus tells Thomas in John 20:27: “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side”.

It’s applicability, not allegory, that Tolkien is interested in. He wants the reader to ask: “Could this mean that?”

These are just a handful of the Christian parallels that can be found in Tolkien. It’s important to remember that none of these comparisons are totally perfect; every metaphor breaks down sooner or later, and that’s OK; it’s what makes it a metaphor and not an allegory. There are no doubt 1,000 other ways of reading Tolkien’s work, and we can be confident that he would have welcomed the multitude of interpretations. But if you’re so inclined, it’s strangely comforting to see a writer’s Christianity shine through even when they’re not trying to show it.

No comments yet