When the US authorities tried to deport Rosa del Carmen, she found refuge inside a church building - living there for two years. Isaac Villegas’ decision to provide sanctuary for an undocumented immigrant may have been politically controversial, but he believes it was line with historic Christian beliefs

During Donald Trump’s first term as US president, our church protected a woman named Rosa del Carmen from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) plans to deport her back to Honduras, where she had fled her physically abusive partner some years earlier.

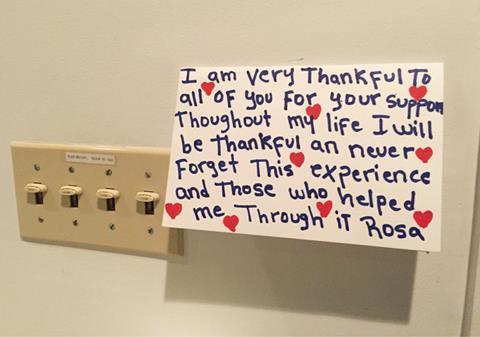

The government had flagged her for deportation even though her case was still in process in the courts. Our Mennonite congregation worked with the Presbyterian congregation that owned the church building to turn an office into her bedroom. She lived there, with us, for two years.

We organised our lives around her care and safety. She depended on us for everyday necessities. Church members ran errands and brought her food. We provided around-the-clock accompaniment, including overnight shifts, in case ICE agents showed up.

This was our collective act of discipleship in opposition to the government’s anti-immigrant policies. We became part of the sanctuary movement to defend undocumented residents from deportation. In 2018, our coalition of churches in North Carolina had six people in public sanctuary - the most of any US state.

Seeking sanctuary

While our ministry of sanctuary clashed with the Trump administration’s agenda, we knew that we were working with the grain of the Christian tradition. Through the ages, churches have opened their doors to protect people. Places of worship have been recognised as sanctuaries to preserve life.

Augustine, the 5th-century bishop of Hippo, gives an account of how church buildings served as havens for people trying to escape the onslaught of Alaric, the Visigoth king, when he invaded Rome in 410 CE. “The reliquaries of the martyrs and the churches of the apostles bear witness,” he writes in The City of God, “for in the sack of the city they were an open sanctuary for all who fled to them, whether Christian or pagan.”

When Jesus told his followers to love their neighbour, he didn’t say to check their paperwork first

Priest and historian Paulus Orosius, a contemporary of Augustine, reports that Alaric explicitly told his soldiers not to trespass into churches: “If anyone fled into the basilicas of the holy apostles Peter and Paul, these, first of all, were to be granted security and inviolability.” Churches were respected as holy sanctuaries of protection.

Now, the sanctuary movement is in the news again. On his first full day in office President Trump rescinded the designation that makes churches and other places of worship “sensitive locations,” protecting them from ICE agent operations on or near their property.

Now religious communities are battling his administration, with some suing the federal government over the change in status, saying that it infringes on their religious freedom.

Believe and belong

Immigration policies are about social formation: about the making of a peoplehood, the construction of our collective identity. The political is personal, reaching into the intimacies of our friendships, of who we belong to and who belongs to us - in our families, schools, neighbourhoods, and religious communities.

The anti-immigrant enforcement operations ripping neighbours from neighbourhoods and parents from children is not only an American problem. Nativism, as an ideology that seeks to preserve the dominance of the Euro-Christian culture, is growing more and more popular in Western nation states.

Through the ages, churches have opened their doors to protect people

According to these ethno-nationalist movements, whose leaders are winning elections, immigrants from the global South threaten the political order and pollute the cultural heritage of white, European identities.

These politicians have outlined a vision for belonging that prioritises fellow citizens. As for those who, according to our legal frameworks and political definitions, happen to live on the wrong side of the citizen-or-alien divide? Well, they’re deportable from our sphere of concern, banished from the reach of our sense of mutual responsibility.

Love thy neighbour

If our laws determine that our society does not belong to them, we can absolve ourselves of our obligations as their neighbours. Because, according to their political imagination, the bonds of citizenship trump the biblical call to love.

The requirements of statecraft short circuit our ethical deliberation. The presumptions of nationalism relieve us from our nagging feelings of care and concern for undocumented others. After all, the law is the law, a social contract to preserve who we are as a people.

Biblical faith is a style of life in which we relearn our relations. To belong to Christ is to reconfigure our lives to recognise the Spirit of God at work in our relationships. When Jesus told his followers to love their neighbour as themselves, he didn’t tell them first to check their paperwork, to see if they were citizens, to verify the legality of their personhood.

To love our neighbours, even if the government wants to get rid of them - that’s the call of the gospel. To seek God’s transformation of our lives - that’s the good news to which I’ve tried to bear witness with the stories I tell in my book.

Read more about Rosa’s story in Isaac’s new book, Migrant God: A Christian vision for immigrant justice (Eerdmans)

1 Reader's comment