In daytime TV, as in all aspects of our lives, we are often eager to reach a quick resolution. But sometimes, the work of forgiveness takes time, says George Pitcher. And rushing it doesn’t help anyone

If only we could see the WhatsApp messages, even if they’re redacted, between the principals involved, we might be able to openly and constructively address what is potentially the greatest constitutional crisis of our time.

I speak, of course, of ITV’s This Morning and the collapse of the relationship between presenters Holly Willoughby and Phillip Schofield.

I’m conscious that I’ve just written one of those sneering, oh-so-superior column intros so often seen in the media. How we laugh at how seriously these trivial daytime celebrities take themselves!

We are literally not afforded, in faith, an option to withhold forgiveness

But actually it is serious. It is serious that our politics have become entertainment, and our entertainment carries political freight. It’s certainly serious for Schofield who, as a result of having a fling with a much younger staffer and then lying about it to his employers, friends, family and colleagues, stand to lose everything.

A moral seriousness

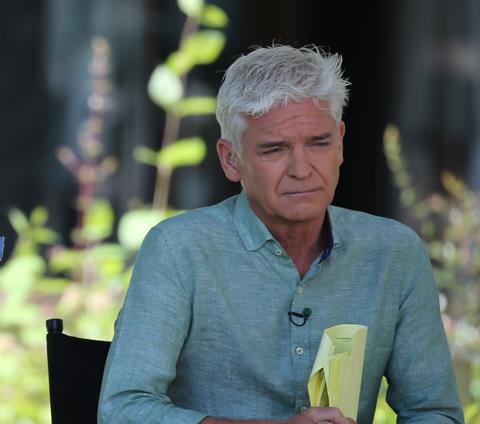

As a parish priest, I’ve seen the shape of that downturned crescent of a mouth and the defeat in the eyes. He may know how to perform, and manipulate a TV audience, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t very close to the edge of irretrievable despair. And that’s a very serious place to be.

It’s also very serious for those who work at This Morning if ITV closes the show. It’s serious for Schofield’s co-presenter Willoughby, who stands to lose a highly lucrative career for something she didn’t do, whatever the condescending criticisms of her actions around it.

There is also a moral seriousness to all this, although I don’t personally think it’s to be found in Schofield’s imbroglio. He has famously described that as “unwise but not illegal” and, technically, he’s right. But claims that homophobia has fanned the fire of outrage at his actions are, I think, wide of the mark.

It’s claimed that if a 61-year-old man had an affair with a 20-year-old woman, that would be more tolerable. I don’t think that’s true in today’s professional environment. In truth, an affair between a 61-year-old woman and a 20-year-old man would have attracted the most opprobrium. And that tells us that it is misogyny that is still thriving in the workplace, rather than homophobia.

A right response

But I don’t think this is where the heaviest moral weight is borne. I believe that’s to be found in how Schofield acts towards his wretched circumstance – and how the rest of us act towards him.

It’s often said that we can’t forgive unless we feel forgiveness inside, in our hearts. But that’s not really how it works. In theological terms, we’re invited to state our forgiveness in human terms, so that divine forgiveness can begin to do its work. So we say we forgive in order to feel that we forgive, rather than the other way around.

I start with the business of forgiveness, because that’s what we’re after. But the stumbling block on the way to it is contrition. We may not believe that Schofield was genuinely contrite in his BBC interview with Amol Rajan (see audience manipulation above), and so we withhold forgiveness. But that’s transactional and, as such, unreflective of divine forgiveness, which is unconditional grace.

It is serious that our politics have become entertainment, and our entertainment carries political freight

In the Catholic tradition, this is a clearer process than in the Reformed. You make your confession – you state it, you say it, whatever you feel about it – and are offered absolution by the priest. Only subsequently do you do your penance. So repentance follows the act of forgiveness, not the reverse.

We’re called to emulate that divine model. Schofield has declared many times that he is “so, so sorry.” We are literally not afforded, in faith, an option to withhold forgiveness. Then he can work on his penance.

A work of grace

By his own report, Schofield’s daughters seem to have got this intuitively. What a lot of divine work familial love can do. By contrast, Willoughby’s unusual (not to say, frankly, bizarre) piece to camera on her return to work on Monday, reflects an artificial concern for others, including I’m afraid herself, rather than the healing of the wound at the heart of the matter, without which nothing else can be healed.

These are demanding requirements. But nobody said it was easy, least of all our New Testament. One further problem is that we’re reluctant to give the grace that is active in all this the time to work, to play it long. So hurried are our lives – especially in TV newsrooms – that we demand instant gratification, a resolution to the story now.

A Catholic friend recently sent me a devotion called Patient Trust. Part of it reads: “We are quite naturally impatient in everything to reach the end without delay. We should like to skip the intermediate stages. We are impatient of being on the way to something unknown, something new. And yet it is the law of all progress that it is made by passing through some stages of instability – and that it may take a very long time.

That must apply as much on a morning television sofa as anywhere else.

No comments yet