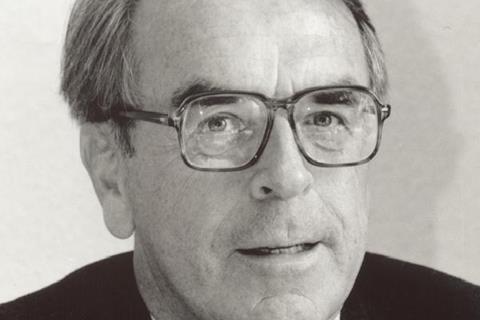

The renowned German professor Jürgen Moltmann, who was praised for being both innovative and traditional, has died at the age of 98. The Principal of Moorlands College, Andy du Feu, considers his legacy

Dr Jürgen Moltmann, the renowned German Reformed theologian and Emeritus Professor of Theology at the University of Tübingen, died on 3 June, aged 98.

His work has significantly influenced Christian theology and he leaves a legacy that evokes both admiration and criticism, bringing new language to our understanding of God, and our place in his world.

Any reflection on his life should not downplay the significance of the times he was born into. Growing up in 1930s Germany, he witnessed the Nazis take power and begin to impose their ideology in every area of life, including religion. Jürgen would later call the antisemitic theology he heard in church “complete nonsense”. He was a 16-year-old schoolboy when he was called up to serve in the German army. His time as a soldier was marked by the bombing of his home city, Hamburg, and the death of his close friend. As the Nazis faced defeat, Jürgen surrendered. It was the beginning of what he later referred to as a new life. As a disillusioned, broken prisoner of war, first in Belgium and then Scotland, he encountered the transformative power of God through reading a pocket New Testament, given him by a chaplain. Speaking of Jesus, he reflected, “Here was someone who understood me, who experienced what I experienced.”

Post-war, Jürgen returned to the ruins of Germany to study theology under teachers who had been part of the Confessing Church, and went on to earn his doctorate before leading two churches. He left pastoral ministry in 1957 to teach theology, and his writings began to gain traction worldwide, even appearing on the front pages of Newsweek, Time, and The New York Times, the latter giving space to a report on how Moltmann’s “theology of hope” was considered avant garde, shunting out the then popular “death of God” theology that had reduced the resurrection of Christ to mythology.

Moltmann’s passionate and rich engagement with the existential questions of suffering, hope, and the end times earned him a reputation as one of the most important theologians since the second world war. While many of his 40 published books are now considered classics, his key works, Theology of Hope (1964) and The Crucified God (1972) stand out.

Theology of Hope proposed that the base line of Christian hope is in the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the coming of his Kingdom. His future emphasis resonated with many, given the threat of nuclear holocaust at the time, but concerns were raised among more conservative voices who feared that overemphasising eschatology could detract from the authority of scripture and the need for personal salvation through Christ. Rather than a concern for exegesis, Moltmann leaned into a more thematic approach, and many of his books stayed away from a “the Bible says” approach. His own encounters with social justice, liberation theology and feminism bleed through into his writing, yet some liberation theologians didn’t consider him radical enough. The reality was that he held these issues in tension, with Miroslav Volf referring to his work as “existential and academic, pastoral and political, innovative and traditional, readable and demanding, contextual and universal.”

God is not recognised by his power and glory…but through his death

Moltmann’s emphasis on the suffering God in The Crucified God offered a powerful exploration of the question of why a good God would allow suffering in the world – a question every youth worker taking assemblies at school has faced. Moltmann asserts that God participates in human suffering through the crucifixion of Christ, providing a counter-narrative to classical theism, challenging us to reflect on the nature of divine omnipotence and compassion. “The God of freedom, the true God, is […] not recognised by his power and glory in the history of the world, but through his helplessness and his death on the scandal of the cross of Jesus” he wrote.

Our understanding of Christian hope is richer for Moltmann’s life and works. In his words, “To live without hope is to cease to live. Hell is hopelessness. It is no accident that above the entrance to Dante’s hell is the inscription: ‘Leave behind all hope, you who enter here’”. His creativity lives on in his writings and those who engage with them, such as Tim Chester in his book Mission and the Coming of God.

Dr. Jürgen Moltmann and his late wife, Elisabeth, are survived by their four daughters.

No comments yet