Leaders are being accused of selling out their Christian beliefs in order to curry favour with the secular liberal majority

A lively debate on how evangelicals engage with mainstream society has been ignited after an article in The American Conservative claimed evangelicalism was “in a bind.” The writers, student Jackson Waters and activist Emma Posey, argue that evangelical leaders in the USA are supporting progressive causes such as anti-Trumpism and other liberal political causes in order to gain credibility with political elites. However, it said, such opinions are out of touch with the beliefs of ordinary Christians, who tend to be far less radical.

The article points out that a large majority of US evangelicals supported Trump. The exception – just 19 per cent – tend to be wealthier, and are often high-profile leaders. These include evangelist Beth Moore, theologian Russell Moore (no relation, but both formerly of the Southern Baptist Convention), conservative commentator David French and US evangelical magazine Christianity Today. “Over the last year, the division between evangelicals and their leadership has only grown,” claimed the article. It prompted a flurry of comment in the American evangelical world, but there are implications for the UK too.

DECLARING WAR

The debate reflects the culture wars that continue to rage. On one side are the liberal left and advocates for social justice issues such as transgender rights, Black Lives Matter and radical feminism. It’s an increasingly powerful movement, characterised by some as ‘woke’. On the other side are more traditional or conservative voices, including the majority of the general public, who tend not to support issues such as unisex public toilets or uncontrolled immigration.

The divide between these two positions only deepened with the election of Trump in the US, and the UK’s Brexit vote. These causes won the support of the masses but were viciously criticised by intellectual ‘elites’ such as politicians, the media and academic institutions.

Waters and Posey’s argument found heavyweight support from Mark Galli, former editor of Christianity Today. After converting to Catholicism last year, he wrote on his blog that evangelical ‘elites’, such as his former publication, “want to appear respectable to the elite of American culture”. They do this, he said, by supporting shared causes such as the environment and racial justice, but ignoring less popular topics such as abortion or male-only leadership of churches.

Galli points out that this is not new: as far back as the 1940s, high profile Christian leaders, including Billy Graham, were positioning themselves as both theologically conservative and intellectually respectable in order to gain influence within secular institutions and wider culture.

In response, author and Holy Post podcast contributor, Skye Jethani, argued that they, and other accused ‘elites’, have in fact covered unpopular subjects such as abortion alongside more fashionable liberal issues such as sexual abuse and racism. “If that makes someone an elitist, I think it just makes them a Christian,” he said in a recent podcast.

THE QUEST FOR RELEVANCE

Each side often attributes malign motives to the other. Conservative ‘elites’ are accused of being provocative to gain approval from the masses, while liberal ‘elites’ are accused of adopting social justice causes to gain the approval of the world.

One of these alleged ‘elites’, David French, said in The Dispatch that the problem lies in the anti-woke, conservative wing of the Church, rather than with the liberal elite that he is accused of representing: “A godless and hateful movement is taking root in all too many American pews, often (and perversely) spread in the name of Christ,” he said. “One set of Christian elites is in conflict with another…[we] are saying what we believe, not merely seeking the applause of the progressive crowd.”

Most worryingly, this acrimonious polarisation appears to be seriously affecting evangelicalism in the US, with some pastors reporting political splits are damaging their church’s unity. An article in The Atlantic by Peter Wehner found that: “pastors now find themselves on the front lines of this conflict, their congregations splitting into warring camps. I spoke with 15 of them, and what I heard was jarring. They told me that nothing else they’ve faced approaches what they’ve experienced in recent years, and that nothing had prepared them for it.”

IT IS MUCH EASIER TO TAKE UP THE CAUSES WHICH OUR SOCIETY SUPPORTS THAN THOSE IT HATES

A KINGDOM NOT UNITED

The UK is different, both politically and theologically, and has to look much further back in time to find an era when Christianity was a significant influence on our culture and politics. Church attendance is considerably lower, too.

Nonetheless, within evangelicalism there are parallels. Probably the most influential Christian leader, at least politically, is the Most Rev Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, who has instant access to the nation’s column inches and TV screens. Since taking on the top job, he has repeatedly advocated for social justice causes and uses the language of the new movement. Recently declaring: “I have white advantage”, he has been dubbed the “Archbishop of Woke” by his right-wing critics.

The conservative clergyman Rev Marcus Walker recently pointed out that many Church of England bishops hold vastly different views to their flocks. Around two-thirds of people identifying as ‘Anglican’ voted for Brexit. However, only one of the 115 CofE bishops publicly backed the campaign. “Guardian readers preaching to Mail readers, as the old saying goes,” Walker quipped in an article for The Critic.

The liberal politics and anti-Brexit views of the CofE leadership have alienated some in the pews. Michael Collins, author of The likes of us: a biography of the white working class (Granta Books) said he was considering leaving his Anglican cathedral due to its liberal politics: “The incumbent Dean and his colleagues catered for an anti-Brexit, middle class Lib Dem demographic, championing open borders and mass immigration, attacking Donald Trump via heavy-handed virtue-signalling from the pulpit,” he wrote in The Critic. “We’re only too aware how a liberal elite denigrates the masses for courting the excesses of the US, yet they themselves import the excessive ‘woke’ causes of American campuses.”

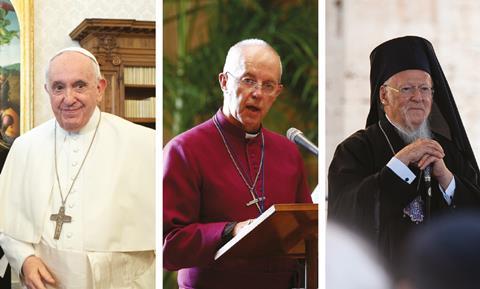

In the other larger denominations, there is also interest in what are often considered more liberal subjects. For example, Welby, Pope Francis and the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Archbishop Bartholomew I, chose to make their first joint statement not about abortion or euthanasia, but climate change.

Is that a problem? Perhaps not. “Expressing concern about racial justice, environmental issues, treatment of immigrants, etc hardly need be the result of narrow moral preoccupations: it might simply be Christian faithfulness,” Alastair Roberts, British scholar and adjunct senior fellow of the Theopolis Institute, told Premier Christianity. “However, I do think that it is fair to say that the expressed values of bishops tend to align quite consistently and predictably with the values of a metropolitan progressive liberal class – from which they have been predominantly drawn – too easily confusing Christian witness with the underwriting of that class’s narrow moral preoccupations.

“There is a great deal of misunderstanding of people who are labelled as ‘elite’ and their motivations,” he continued. “There are often much more charitable constructions to be placed upon their actions, even when we might strongly disagree with them…I would like to see a bit more good faith interaction between Christians of different classes, attempting to put more charitable constructions on each other’s actions and motivations where possible.”

David Robertson, the conservative commentator formerly of Solas, told Premier Christianity that the temptation to accommodate secular elites applied to both progressives and conservatives: “My view is that it is much easier to take up the causes which our society supports than it is to take up those it hates.”

I WOULD LIKE TO SEE A BIT MORE GOOD FAITH INTERACTION BETWEEN CHRISTIANS OF DIFFERENT CLASSES

He pointed out that there is also a pull to be reactionary as well as to be fashionable: “There is a temptation to curry favour with the cultural elites and a reluctance to challenge,” he acknowledged. “Equally there is a temptation to seek to be contrarian – to attack the culture – but play to the gallery of your own supporters. The Christian view needs to be more nuanced, diverse, compassionate, courageous and subtle.” Quoting Jesus in Matthew 10:16, he concluded: “We are to be as wise as serpents and harmless as doves.”

French, said in The Dispatch that the problem lies in the anti-woke, conservative wing of the Church, rather than with the liberal elite that he is accused of representing: “A godless and hateful movement is taking root in all too many American pews, often (and perversely) spread in the name of Christ,” he said. “One set of Christian elites is in conflict with another…[we] are saying what we believe, not merely seeking the applause of the progressive crowd.” Most worryingly, this acrimonious polarisation appears to be seriously affecting evangelicalism in the US, with some pastors reporting political splits are damaging their church’s unity. An article in The Atlantic by Peter Wehner found that: “pastors now find themselves on the front lines of this conflict, their congregations splitting into warring camps. I spoke with 15 of them, and what I heard was jarring. They told me that nothing else they’ve faced approaches what they’ve experienced in recent years, and that nothing had prepared them for it.”