Many Christians joined the Queen in celebrating 60 years of Songs of Praise, but a third of millennials have never even heard of the show. With the BBC still yet to appoint a new religion editor, has the corporation grown stale when it comes to Christianity?

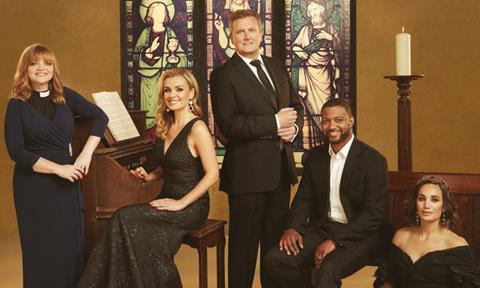

The BBC’s flagship religious programme, Songs of Praise, has just marked its 60th anniversary. Past presenters and guests packed Westminster Abbey to celebrate and the Queen sent a message of congratulations to the world’s longest running religious TV show, saying: “[It] has shown Christianity as a living faith.”

But amid the celebrations, there are broader concerns about the BBC’s coverage of religion. Particularly among younger and non-denominational believers, Songs of Praise is widely panned as an irrelevance whose continuance shows how poorly the BBC covers Christianity. Others view it as a cherished heirloom that must be protected, bemoaning its Sunday lunchtime ‘graveyard slot’ and accusing the BBC of being embarrassed by the iconic yet unfashionable show.

In the 1990s, the programme drew as many as six million viewers each week. By 2009 that had almost halved to 3.4 million and, today, viewership has dipped below a million. In a recent YouGov survey, only 17 per cent of those polled said they liked Songs of Praise, compared to 35 per cent who disliked it. A third of millennials have never heard of the show. Yet for all the criticism, Songs of Praise has made it to 60 years and, every week, almost a million Britons watch a show exclusively dedicated to Christian worship. On a largely secular network, that is no mean feat.

DECADES OF NEGLECT

In 2016, Songs of Praise became one of the first BBC shows to be put out to tender. While the quality has not dipped since it was outsourced, one former BBC producer said it felt like the corporation’s religion department fizzled out as a result. Today, Christians working in the BBC speak of a lack of imagination around religious programming. Novel, creative ideas for shows about faith languish unpitched due to a conviction, whether misplaced or true, that they would not garner interest within New Broadcasting House.

One Christian broadcaster said today’s situation was the result of decades of neglect. The BBC Religion department was one of the first to be relocated to Manchester, which isolated it institutionally and led to a series of bosses quitting in frustration. A lack of religious literacy among BBC staffers, who are younger, liberal and less interested in faith than the average Briton, adds to the problem: “Instead of seeing religion as a wonderfully rich area to make programmes about, which deals with all the things that matter in life, there is a black hole,” he said.

THE CHALLENGE FOR THE CHURCH

The BBC has a public service broadcasting requirement to produce 115 hours of religious content on TV and 370 hours on radio each year. In 2020-21, it exceeded all its targets. But heavyweight figures in the media world have pushed back against the idea that religion needs to have its own reserved hours. Instead of obsessing about how to twist the broadcaster’s arm so it still covers ‘our stuff’, why not trust that stories and characters from the Church are so innately compelling they can win airtime on their own merits?

“As a news editor, there is massive appetite for religion stories because they’re actually about how we live,” the former head of BBC News, James Harding, once insisted. Rather than wade through “Day 400 in the Big Brexit House”, the media should be keen for religious affairs stories, which are about “sex or families or living or dying”, he added.

Perhaps, therefore, the problem is a lack of media literacy on the part of the Church. Are Christians not getting enough airtime because we are not willing – or able – to present our best stories?

Yet the case can still be made that religion is overlooked at the corporation. For decades, despite much lobbying, the BBC did not have a religion editor, despite appointing senior specialists in everything from politics to China to health. Eventually the job was created, and later given to Martin Bashir, but the post has now lain empty since he resigned six months ago following accusations of misconduct around his infamous Princess Diana interview.

The BBC told Premier Christianity the post will be advertised “shortly” but, until that happens, just one producer is responsible for all of BBC News’ coverage of religion. “I don’t think they would have done that for other areas,” a BBC source said.

The senior Christian broadcaster said there remained a stale, institutional mindset at the corporation when it came to Christianity, encapsulated in the worthy-but-tired Songs of Praise. Staff still thought of religion in narrow terms and were ignorant of the dynamism and variety of 21st Century faith. The decline of organised religion is confused for a lack of interest in faith and spirituality more generally, resulting in “relics of the past” such as Songs of Praise persisting while anything “interesting and stimulating for a new generation” passes the corporation by, he suggested.

CHRISTIANS WORKING IN THE BBC SPEAK OF A LACK OF IMAGINATION AROUND RELIGIOUS PROGRAMMING

BBC management is aware of the criticisms. In 2017 it commissioned a review of religion coverage and declared 2019 the Year of Belief. But, while it continues to churn out faithful regulars, there is a growing crisis of confidence in its ability – or willingness – to cover faith well.