The former mayor of London candidate speaks to Abi Thomas about arriving in England as a refugee, encountering Jesus in a pub and what motivated him to raise millions to help those in poverty

For reasons that were never fully explained to him, Ram Gidoomal CBE and his family were forced to flee their home in Kenya when he was just 16 years old. Having previously left India during the 1947 partition, they said goodbye to the life of wealth and comfort they had created for themselves in east Africa to arrive in a hostile 1960s London as refugees once more, with no money and little to their name.

Gidoomal was brought up in both the Hindu and Sikh faiths, but Jesus started to become real to him through the lyrics of a song he heard in a London pub. At the time, he was a student at Imperial College London. His business skills had won him a scholarship and would eventually lead to him earning so much money he couldn’t even spend the accruing interest, he tells me.

By the age of 37, Gidoomal’s businesses were so successful that he was preparing to take early retirement. But God had other plans.

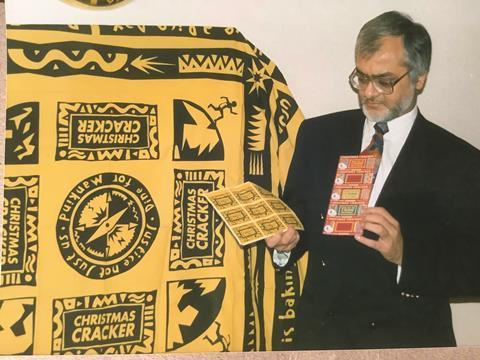

During a business trip to Mumbai in 1988, Gidoomal visited Asia’s largest slum, where he met a five-year-old boy living in filthy conditions. The encounter changed his life. He resigned from his position as CEO of Inlaks – the company was worth £130m and employed 7,000 people at the time – to set up the Christmas Cracker Charitable Trust. “I realised that God did not call me to become something that I wasn’t, but instead to use what I was and what I had been given in new ways”, he says.

Christmas Cracker raised more than £5m by encouraging young people, often from church youth groups, to set up temporary businesses in the run-up to Christmas that raised money for people in poverty in the global South.

These included “tune in, pay out” Radio Cracker stations where listeners could pay to hear their favourite songs. Young people also opened ‘Crackerterias’ – cafes that sold meals, often created from donated food, alongside other fair-trade goods.

Gidoomal has since advised government departments, stood as the Christian Peoples Alliance candidate for mayor of London and been awarded a CBE for services to the Asian business community and race relations. He has served as chair of Christian organisations including Stewardship, Traidcraft and the Lausanne Movement, and is vice president of The Leprosy Mission.

But as the child of a “twice migrant” family (like Rishi Sunak, Suella Braverman and Priti Patel, he tells me), he is passionate about caring well for refugees. For those politicians in charge of policy-making, he has a clear message: “Please bear in mind humanity; please let us not forget our roots.”

When I arrived in the 1960s, it was the time of Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech

What are your memories of your childhood in Mombasa?

Oh, it was fun! The beach is one big memory. And the food! Walking home from school with friends there were barbecue fires cooking cassava with red chilli, salt, pepper and lemon. Passing by mango trees, you tear off the skin and start sucking it – just sheer delight.

My family were Hindu, but also practised the Sikh faith because of the part of India we come from. We would go to a Hindu temple on a Monday and a gurdwara on a Wednesday. I was sent to a Muslim school and sometimes we were invited to the mosque. We may not have been invited into the holiest place, but outside in the courtyard we would have an amazing celebration with dancing and music.

Daddy’s main business was a shop selling silk saris and travel goods. He also had a lucrative side-line in finance. We didn’t want for anything. We had a large flat with 15 rooms, and a Mercedes, a driver and cooks – until Daddy got his notice to leave.

Tell me about that day.

We were enjoying ourselves, the usual party, people bringing food in – mincemeat, keema, lamb curry – all the fragrances filling the place. Suddenly, Daddy walks in and there is silence just for a few seconds. You couldn’t miss it.

My sister said: “You’ll never believe what happened. Daddy’s got a deportation order…24 hours.” The reason was never explained to me, although I was reading in the local newspapers about other people receiving such notices for misdemeanours, like not replacing the picture of the Queen with a picture of the newly elected president of Kenya. I remember thinking: What happens to the business? What happens to our money? They’ve lost it once before, surely not again? But it was [happening] again: everything lost.

What was it like starting afresh in London?

When I arrived in the 1960s, it was the time of Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. It meant that my journey from home to school was a nightmare. To those hearing such words, it gave licence to abuse us.

We walked in groups to feel more secure. Daddy had bought a corner shop and behind it was Loftus Road, the Queens Park Rangers’ [football] stadium. Many of the boys were wearing blue and white scarves, so we invested in those colours as an added layer of protection.

There were 15 of us living above the shop, with four bedrooms, one bathroom and a toilet. It was fun, but it was painful – you couldn’t eat any of the sweets, because that was your profit!

Did you receive early lessons in business from your family?

Our lunch table conversations in Mombasa were all about the deals that had been done. I heard about one deal where a ship had landed and somebody wanted to exchange 10,000 Rhodesian pounds into sterling.

The rates of exchange were agreed and Daddy made a clear profit of £2,000. That excited me. And the same thing [was] repeated in London. I learned supply, demand, market research – all the important basics for big business.

Tell me about your experience at Imperial College London?

In the third year I had to stay at the university halls of residence. I had never been away from home and I was very lonely. I found my way to a pub and sat down. There was a group singing ‘Put your hand in the hand (of the man from Galilee)’, and they explained: “That’s Jesus.”

I thought: Jesus is not the man from Galilee, he’s the man from the city of London! Jesus is English, he’s white, he’s blue eyed, with a bowler hat and pinstriped suit. [I thought to myself]: Let me have a little argument with them.

I gave them my room number and a guy came to see me – he was tall, blue-eyed, blond, and he was an economist in the city of London! I argued with him and he took me to the book of Isaiah and to the Gospels and showed me how they’re connected. When I saw the level of evidence there is for Christ, I thought: Wow! There’s more to this than meets the eye.

In Revelation 3:20 I read: “Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me.” I opened my huge window and invited Jesus in.

I was on my knees and I said: “I want to accept you as my Lord and saviour, please forgive my sins. I have all this karma that I have carried through my life and even from previous incarnations, but what I’m reading here in the Bible says you forgive all sin. So I’m going to take that for a fact.” There began my small steps of faith.

Tell me about your life-changing business trip.

I was in India to buy prawns [for my seafood business] and my last port was Bombay [now Mumbai]. I asked the people I was meeting to show me what their businesses did in the local community. Some pastors and community workers said to me: “We meet here every week at five in the morning. We have a Bible study in the Dharavi slum, we then do work amongst those who are struggling.” So I said: “Take me there.”

I was shocked. I saw this five-year-old kid. They told me the slum lord wouldn’t allow him a box [for shelter], so he slept in a water pipe. I said: “Can I go and see it?” They said: “You won’t get anywhere near it – it stinks and it’s a health hazard.” I said: “What about his mother?” and they took me to these girls who had just hit puberty, locked in cages. I asked: “How does the boy survive?” I was told that after everybody else has raided the rubbish heap, he eats.

I went home on my first-class flight that night and was offered champagne. I was absolutely sick – I couldn’t believe what I had seen and heard. I took my seat, waited for the lights to go off and I broke down and wept.

The impression of that young boy was so embossed in my mind that when I arrived back I said to Sunita [my wife]: “I can’t even go back to work. Every time I sit at my desk, that image is haunting me.” We prayed: “We don’t need a yacht. We don’t need a plane. We can’t even spend the interest we are earning. The kids can go to the state school; we can sell the big house. Let’s do something different.”

And that’s how your work with Steve Chalke and Christmas Cracker began, helping young people set up businesses to fund relief work?

Yes. We raised nearly £5 million over seven years, but what was more exciting was seeing 50,000 youngsters motivated and excited to make a difference!

When I saw the level of evidence there is for Christ I thought: Wow! There’s more to this than meets the eye

You also learned a lot from your colleagues who worked in the Dharavi slum?

Yes, they had an amazing influence. They shared everything, from photocopiers to staff. When Christmas Cracker was set up, I said to Steve Chalke: “We will not set up a separate office or a separate anything. We are going to subcontract to existing charities.” It was done with very little overheads so that the maximum amount that the young people raised went to help those who were in need.

Where do you see that healthy balance between charity and business?

It’s a combination of the two. I chaired Traidcraft PLC for nine years, which also has a charitable arm, Traidcraft Exchange. You do need aid, because people are suffering, but you also need trade to help them with the dignity that jobs and a business can bring. It’s got to be done in a sensitive way and in a way that uplifts and addresses the root cause of what is going on.

What would like to say to those in power about the welcome we give to refugees and asylum seekers?

Those first days that refugees come into this country make such a deep impression. If we can give them [a warm] welcome and do something positive, that will give them a positive image. A civilisation will be judged by how it treats the most vulnerable. Please bear in mind humanity, bear in mind compassion.

Looking back, what impact has following Jesus had on your journey?

Total impact. When I read the New Testament for the first time, I saw the simplicity of who Jesus was and I said: “This is an example to follow.” I see the power of prayer – over 50 members of my extended family became followers of Jesus.

I know how important how I behave is – how I relate to others has an impact. My mother was the first person I had to relate to, and over seven years she saw the difference Jesus was making in my life. Once she became a believer, all barriers were gone!

To me, it is a daily walk with the Lord bringing about a daily change in our lives, being more Christlike in what we seek to do.

My Silk Road by Ram Gidoomal (Pippa Rann books) is out now.

To hear the full interview listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on Saturday 7 January 2023, or download ‘The Profile’ podcast premierchristianradio.com/theprofile

No comments yet