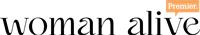

As London Community Gospel Choir celebrates its 40th birthday, their founder explains why he’s still intent on making music for the masses

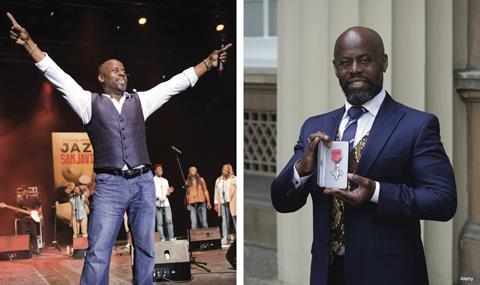

Rev Bazil Meade MBE is no ordinary septuagenarian. The 71-year-old co-founder of Europe’s leading gospel choir has played in front of some of the highest profile international audiences, and continues to perform with extraordinary energy, exuberance and flair.

London Community Gospel Choir (LCGC) in 1982, his approach was considered scandalous. For encouraging his team to drop the traditional choir robes, wear make-up and perform alongside non-Christian artists, he was accused of betraying the Church. But in the 40 years since, Meade has taken LCGC to dizzying heights, and largely won over his critics. As well as appearing in the award-winning film Love Actually, the choir has supported musicians such as Madonna, Sting, Sir Paul McCartney, Justin Timberlake and Kylie Minogue.

They’ve performed for the Queen and Nelson Mandela, and Meade has received multiple accolades, including an MBE, for services to gospel music.

Before all this, Meade lived a simple life on the island of Montserrat in the West Indies. His mother left to work in the UK when he was young, and he was raised by his father – an industrious farmer. But when he was nine years old, his mother sent for him to join her. Making the two-week journey by ship alone, he arrived in 1960s England where signs on shop windows read: “No blacks. No dogs. No Irish”. He would frequently encounter racist abuse in the street.

At school, he was one of only two non-white children, but it was at home where life was toughest Domestic violence eventually caused him to leave home as a teenager, and a career in music soon followed.

Having survived poverty, racism and domestic violence, Meade is undeterred in his mission to ensure LCGC continues to share the good news with the masses. Much has changed over the past four decades, but Meade remains crystal clear about one thing: he isn’t in the music business to please Christians. He does it for those who aren’t…yet.

You speak with fondness about your dad. What type of man was he?

He was a hardworking man. One thing he instilled in me and my brother was that you work for your daily bread. You do not beg. If you are healthy and you can work for yourself, you find bread; whether it is in the sea, the soil or from the trees around you. Be generous to people. When you have more than you need, you can help others.

He was the caretaker of the local Methodist church. And that job was his way of giving back to God and to the community. We always went to church on a Sunday.

When you moved to England aged nine, there was a growing uneasiness in your family home – particularly with your stepdad. What happened?

To begin with, my stepfather was accepting of me. But as I grew up, I was more of a threat because I approached him about the way I felt he was treating my mother. I would hear the arguments from their bedroom at night. The whole thing was so painful and frustrating for me. I lived with pent-up aggression. One lady came to me at church and said: “Your face looks like you’re always ready to fight.” I will never forget that. I was ready to burst. I wanted to unleash on somebody.

I approached him the day after a really bad argument. I told him I didn’t care how big he was or that he was my mother’s husband, he obviously didn’t love her and he was abusing her. He thought I was disrespecting him, so he came at me with a hammer. I was strong enough to hold him off and was able to get away from him. I ran out the house.

What are your reflections on that now? Have you been able to forgive him?

It’s a big question for me. I have never seen him again. As I grew up, I thought of him as just this man in my mother’s house. He wasn’t my father.

Tell me about the influence of Dr Olive Parris – she was instrumental in your life, wasn’t she?

She was the youth minister at my church. I think she saw the anger that I carried. She said: “Stay with me until you decide what you want to do.” That was the best decision I could have ever made. I began to find that there was a different way to live. I didn’t have the negative, aggressive, argumentative environment that I existed in at home.

I heard a rumour that she gave you some vinyl records and asked you to form a choir – which was the beginning of LCGC…

She was a travelling evangelist, holding meetings all over the UK and abroad. I went to places like Greece, Canada, Bermuda as her accompanist, her musician. In our own church, there wasn’t a choir, so she said: “I have these gospel records, which I need you to listen to and teach.”

So you formed the London Community Gospel Choir and, after that, there was no stopping you.

Absolutely. But I had many discouraging things said to me. Like: “LCGC is finished. You need to look after your family.” I’d left my previous job, where I was earning good money, and I didn’t know how to negotiate with people who [wanted] to hire the choir. I made many mistakes.

We were being ridiculed for being ungodly, singing with non-Christian people, singing in non-Christian environments. But I was convinced that God gave this particular mission to me. I didn’t see myself as anyone’s superior; I felt it was God’s plan.

Did you always intend for the choir to perform with non-Christians, or did that evolve?

It evolved. I began to realise that the power of gospel music goes beyond someone standing in the pulpit with a Bible. That is simply servicing a congregation who were already converted. The word of God tells us that we should go into the world. For me, that points me away from church services, into unknown territory. I realised the purpose of LCGC was to service the non-Church community.

How do you maintain integrity in your faith and mission while operating in secular environments?

It’s edgy and it’s a difficult area for some to understand. But I always tell the story of when we were at Live 8. We were in our green room – about 80 of us – having our devotions and singing. The door was open. Musicians walked past and saw and they asked if they could be part of what was going on. One said: “My skin began to tingle just hearing the sound that you got.” I didn’t have to preach a sermon to them. We were sowing a seed into people’s lives, and that’s what I am about.

When you look back over your life, is there anything you would do differently?

Oh, I know I made many mistakes! One of the casualties of this journey has been my marriage to Andrea. I thank God we are friends; we have a lovely family, lovely children and grandchildren. We’re very proud of what we achieved together. I would love to have made different decisions. I think we’d both say that.

I think the way that the business side of LCGC developed could have been different. I always wanted to have independence. I’ve never wanted to be under the control of a record label, because I’m a black person and I’m very proud of that. I’ve always wanted to retain, within the leadership, somebody who looks like me, because we don’t have much as a community that the rest of the world can look at and say: “The black folk in the UK have established and have maintained something that is iconic, that we can look upon and celebrate.” So I am now handing over the reins to Leonn Meade, the two-year-old baby who was on stage with LCGC at the

Queen’s 60th birthday. We will go on to do greater things, I’m sure, with God being involved.

When you were launching LCGC in the 1980s, there were interesting things happening in the white Christian music scene. What differences do you see in how these parts of the Church and their music function?

It’s always been tricky in terms of opportunities. The record label owners, the people with the resources, are white – so it’s much easier to get a white artist up onto a stage, get them recorded and get their products into the Church and the wider world.

In the black Church, we have professional artists who are earning their living playing music for [mainstream white artists like] Sam Smith, Ellie Goulding and others [and then] playing for their church on Sunday, because that’s where their heart is. If the black Church would see this and support it, we would have more gospel choirs in our churches.

The white Church community organised themselves. They have the support systems. They record their artist’s music, which they then market and promote into the black community. But gospel music is thrown in the dustbin. I do not feel happy about that. I cannot celebrate that, because its denying who we are. It makes me want to cry. It is not being celebrated.

Does the legacy of slavery and inequality play into the differences you’ve described – the way in which white churches seem to have more structured systems and do more with their white artists?

Yes, it impacts on every aspect of life. The struggles we have are handed down from slavery, but I don’t think these are an excuse. We assimilate at the expense of our culture. The UK is made up of many different cultures – Irish, Scottish, Welsh and English. We should celebrate our culture. We can do this and recognise and celebrate others as well as our own.

So you’re saying the African diaspora aren’t celebrating the authenticity of their own music?

Yeah, absolutely. There is an imbalance that has happened because our leaders are not celebrating our style of worship. You listen to a gospel choir in full swing, then listen to a praise and worship team – different animals, a different style of expression.

There is much more groove and passion; gospel music tells stories. Our forefathers are slaves. This is the journey of gospel music. How on earth can we throw that into the dustbin? I cannot understand it. We can take the praise and worship and mix it with our services, but we must also celebrate gospel music because it is our culture. It’s our inheritance.