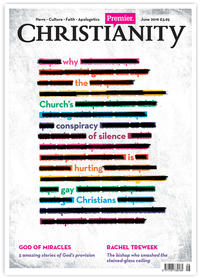

On the night of 10th September 2014, Lizzie Lowe, a much-loved and gifted Christian teenager, walked into her local park and hanged herself. In an interview several years later, her priest, Rector Nick Bundock, with dark circles around his eyes and sorrow in his voice, described the “conspiracy of silence around the issue of sexuality that had been the crucible in which Lizzie had existed in those months up until her death”. St James and Emmanuel, the evangelical Church of England parish where the Lowe family had been committed congregants for many years, had chosen not to openly discuss the subject of sexuality for fear of stirring up “a hornet’s nest”. And so Lizzie, who was grappling with feelings of love and attraction towards other girls, couldn’t see how her faith – which was so precious to her – could be reconciled with her sexuality. In the end suicide seemed the only option. She was just 14 when she died.

Lizzie’s death sent St James and Emmanuel spiralling into a sobering period of mourning and re-evaluation. I wanted to know whether, five years on, the “conspiracy of silence” Bundock described was alive and well in our churches, or whether gay Christians were finding the Church to be a more welcoming and inclusive place. I spoke to people from both sides of the theological debate, as well as pastors ministering in Brighton among a large LGBT community. What I found out from those who would speak on the record – and those who wouldn’t – was hugely revelatory about where the Church now stands.

Sacred celibacy

Author and speaker David Bennett describes himself as a celibate, gay Christian. His extraordinary story of encountering Jesus after someone prayed for him in a pub, and how that transformed his life as a gay activist, is told in his book A War of Loves (Zondervan). Bennett upholds the traditional Christian sexual ethic of marriage being between a man and woman, and sex outside of this – be it heterosexual or homosexual – is sinful. As a Fellow at the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics, he is often tasked with defending this position, which many in the mainstream have branded bigoted.

“I think what the Bible teaches about sexuality is that we were created originally very good and then we fell, and now our desires are somehow impacted and they’re twisted or turned away from the will of God throughout our lives,” he says. “And that can take a heterosexual form, that can take a homosexual form, but that needs to be reoriented around the lordship of Jesus, it needs to be redefined.”

The kind of “turning away from the will of God” that Bennett describes is seen in same-sex attraction and in heterosexual lust – “heterosexual desire can produce as lustful a way of living as homosexual. I think the difficulty with homosexual desire is that it can never be sanctified in marriage in the sense that Paul talks about in 1 Corinthians 7,” he explains. According to Bennett, affirming gay marriage would be “a betrayal of the gospel of Jesus Christ”.

But Bennett sees the current debate as having far broader implications for the Church than just marriage. “We need to become whole in God. And I think this question of same-sex desire is actually calling us deeper into the gospel, and deeper into what it means to be whole,” he says. “What I’m not saying is that gay people should just be celibate,” he adds.

“What I’m saying is that every Christian should be celibate until otherwise invited by God. And I haven’t been invited out of my celibacy into marriage to an opposite sex partner – yet. I may be and I don’t know if that’s going to happen in the future, but it could… I have gay friends who are actually married to opposite sex partners and are really happy. So I think God’s story in every individual life can take a different form.”

Bennett is keen to explain that marriage is not the end goal. “I think the idea that you need sex to be whole is really the crux of the problem, because Jesus never had sex and he’s the greatest example of human flourishing.” Human flourishing is what Bennett is so passionate about and it sits at the heart of his own “personal revelation” about celibacy (he used to advocate for gay marriage until “my love for God grew deeper and deeper”). It’s a message he wants the whole Church to grasp more fully. “I think that the cultural context we live in has meant that we’ve created an idol out of romantic love and then that’s twisted our views of marriage,” he tells me. “We need to recognise that marriage is a temporary state that God calls some Christians into.”

Bennett is critical of a Church culture where getting married and having children is elevated beyond what scripture teaches and held up as the ideal for everyone to aim for. He believes the Church should present a different picture to the world, one which values celibacy as “sacred” and encourages close relationships that reach beyond the nuclear family. He argues such a message would be attractive to non-Christians who are “hungry” for true intimacy. But, all this will require a radical shift towards self-sacrifice and genuine discipleship, he believes.

“When people ask me: ‘What’s one way that we can love the gay community or help gay Christians come into biblical teaching and live Jesus’ way?’ I always say: ‘Don’t be hot or cold. Be hot – be the full deal, give up your life in equal measure to what a gay Christian would need to give up to be living in the kingdom of God.’ Give up your sexuality, radically, give up your money, radically, give up your life for Jesus. Then, that will create a space in the church; when a gay person comes in and gives up their life to Jesus, there’ll be a whole lot of brothers and sisters that understand what a sacrifice like that is, because they’ve gone through it themselves in different areas.”

Not ashamed

When I speak to Jade Irwin, the newly appointed national director for Diverse Church, an organisation committed to the advancement of Christianity among LGBT+ people, it’s clear she thinks celibacy is an unsatisfactory answer for gay Christians, though she respects the fact that some people affiliated with her organisation will hold this view. “To be honest it can sometimes be a little bit patronising in terms of: ‘But you can have this really fabulous friendship with Jesus and friendship with other males that will fill that big void.’ It doesn’t fill the void.”

Irwin is herself in a committed relationship with a woman. Both of them are churchgoers but they’ve come to a different understanding from Bennett of what it means to be gay and Christian. For Irwin, who grew up in Northern Ireland and still lives in Belfast, the journey started at university while she was studying for a degree in sociology. “I remember sitting with my sociology textbook open and my Bible open, literally simultaneously, as if you could kind of cross-reference. And I remember being really, really conflicted, because at the time I was going to a church that was very conservative.” Irwin says that sexuality wasn’t especially spoken about at church but there was a strong undercurrent of: “A man and a woman meet and get married and have children.”

“And then in sociology lectures, I was hearing things like ‘religion as humanly constructed’, ‘gender as humanly constructed’, ‘sexuality as humanly constructed’. I just remember feeling completely undone by the whole thing,” she says. “I really started to search my own self, in terms of: what is my faith based on? Do I know Jesus for myself or do I know somebody else’s Jesus? And why is it starting to sit so uncomfortably with me that if someone doesn’t fit this very, very strict box, it doesn’t sound like good news?”

During this period of questioning she was invited on her first-ever date with a woman. After deliberating (Irwin was still unsure about exploring her sexuality at this stage), she finally plucked up the courage. “I remember coming home, and just thinking: ‘I think I have made this into a topic or an issue’, and that’s the way the Church really spoke about it; that it’s this kind of problematic issue. And the experience I’ve just had was nothing but lovely, and very respectful, and really fun.” That was the start of Irwin acknowledging to herself that she was gay: “That took a long time, but actually it’s something to be delighted about, certainly not ashamed about.”

Irwin tells me that while she thinks theology and the Bible are “really important” she’s aware the Church’s interpretation of scripture has “changed really substantially over time, and across contexts and across history”. Perhaps that’s why she isn’t interested in “verse wars”, where she’ll “pick a verse out, add a bit of my own context and meaning to it and throw it back at you”. She’s referring to the debate concerning what biblical writers meant by words such as ‘homosexuality’ in their historical context. In more recent years, some have argued, for example, that the Bible only condemns abusive and coercive relationships between older men and younger boys, not faithful, loving partnerships between members of the same sex.

Bennett doesn’t think these interpretations add up: “You have not one scripture that is positive or affirming of same-sex activity in the Bible.” But for Irwin, it’s less about specific verses and more about “the trajectory of scripture, the heart of Jesus”. She says: “What I see over and over and over again, is Jesus is unhappy with people being on the outside. The kingdom of God is upside down, the kingdom of God is a woman looking for a coin, the kingdom of God is a shepherd looking for sheep. This stuff was just ridiculous, almost, at the time. And I think right now, the kingdom of God is found the most strikingly in the most unexpected places. So the kingdom is found, dare I say, in a gay bar.”

I ask Irwin whether a church that holds to a traditional Christian ethic on sexuality can ever be fully inclusive. She replies: “With respect, and I really mean that, for churches that hold that viewpoint, no, I don’t believe they can be fully inclusive, because an LGB and T person cannot feel of absolutely equal value for who they are, without having to suppress or change a part of themselves, in order to be fully included. Do I believe that church could be really, really welcoming? Yes. Do I believe that church could be a place of solace and of health and of life and of purpose and family and benefit for an LGBT person? Again yes, as long as they’re absolutely upfront about their theology, and that person can make an informed decision about how that sits with them.”

Although Bennett and Irwin disagree on sexual ethics, they both think transparency is important. This is borne out through conversations I have with other gay Christians who haven’t always found evangelical churches to be the most welcoming places. Sarah Hagger-Holt, who has written a “survival guide” for LGB Christians describes how she spent several years worshiping in evangelical churches during her 20s but grew tired of “wanting to get more involved but being kind of knocked back”. This, she says, has been a common experience among her friends. Churches might have a line on their websites saying “everyone is welcome” or “come as you are”, but those in same-sex relationships might be restricted from serving in leadership roles. Hagger-Holt finally found a “spiritual home” with the Methodists where she became a Methodist local preacher, but the challenges haven’t disappeared. She tells me some of her gay friends are finding that as they grow older and have children, some want to take their families to churches that have thriving children’s work – but many of these are conservative evangelical churches where they wonder if they’ll be fully accepted and included. Like other gay Christians I spoke to there was a sense that choosing a church – or just turning up on a Sunday – has many more implications and considerations than it has for heterosexual Christians.

“I think it would be great for churches that do seek to be inclusive to be quite explicit about that,” says Hagger-Holt. “If you are someone who is LGBT and you see a sign outside the church that says ‘All are welcome’, you may still carry with you bad experiences that make you think: ‘That’s all very well but that doesn’t mean me.’” When I press her on whether churches that hold traditional views on sexuality can be a welcoming place for LGB Christians, like Irwin she questions whether it can work, saying: “It’s hard to hold that together.”

The plausibility problem

The problem that some conservative churches have had in trying to balance inclusion and scripture, says pastor and author Ed Shaw, is that they tend to major on the truth and minor on grace. Rather than helping their congregations envision “what alternative stories the Bible is providing”, they just say: “The Bible says no” to gay relationships. Shaw, who is himself same-sex attracted and celibate, has written a book, The Plausibility Problem (IVP), about precisely this perceived dichotomy. He explains it like this: “When you say to a same-sex attracted young person ‘God’s calling you to a life of singleness’, people think it just doesn’t seem plausible. How could you possibly thrive as a human being and not have sex? How could you possibly enjoy life? How could you possibly get the intimacy that you need to experience as a human being?...The reason we think it’s implausible, the reason we think it’s not doable, is because we have basically got a whole host of things wrong.”

Shaw’s view is similar to Bennett’s: that the Church is idolising marriage, failing to present singleness as a gift and lacking in self-sacrifice. But even if the Church were to start presenting the case for celibacy more positively and intentionally, complex pastoral situations would still exist. What about the lesbian couple with children who turn up to church? Would becoming a Christian entail divorce for those in same-sex marriages? If you bar those in gay relationships from serving in leadership positions, should you apply the same rule to the twenty-something male student who is sleeping with his girlfriend?

Shaw says that once someone understands that Jesus is Lord (and that must come first), their whole life will come under the lens of reevaluation, and one aspect among many that may need to change will be their thinking about sex. It’s a radical message that has driven at least one lesbian couple from his church in the past – something Shaw found “deeply painful”. “They wanted to know if it was an inclusive church,” he tells me. “I wanted to say that we are an inclusive church in the way that I understand it. But I knew it wasn’t the way they understood that.”

Shaw says that as difficult as it is, it’s right for churches to have these conversations and be “open and honest”. Many, he says, have not been so bold for reasons as varied as “media pressure”, fear of “their brand being undermined”, that it could “hinder evangelism”; “stop government funding” or simply because they don’t want to ask their congregations to “deny other people what they couldn’t cope without themselves”. But what’s the outcome of that strategy? “If a church leader’s silent on the issue of Christian sexual ethics, inevitably their church family will be more affected by secular ethics when it comes to sexuality because that’s all they’re hearing,” Shaw responds. “And so a lot of church family members have changed their mind on the issue, not because their pastor or church leader has changed their mind on the issue, but because they’ve never heard what their pastor thinks or what the Bible teaches.

“I genuinely want to be empathetic to the fear out there, and to the pastoral challenges out there. I’m a pastor myself. But the long-term effect of keeping silent, it’s disastrous pastorally and disastrous for the Church’s witness.” And, he explains, the people who get most hurt are gay people in churches “who have never had any help on what it means to be Christian and same-sex attracted or gay”.

Given the intensity of the debate, it might be tempting to take a step back and declare homosexuality a secondary issue. But Shaw believes this is an area that Christians must not compromise on. “If we start as it were to retreat wherever the cultural battle is, we’ll keep retreating. And we’ll retreat on ‘Jesus is the only way to salvation’; we’ll retreat on issues around abortion and euthanasia… Most liberalism is fuelled by a loving desire for more people to get the gospel, I really see that in my liberal friends but, by giving up bits of the gospel to make it more acceptable, you lose the gospel, and people outside don’t want to respond to something when they see that you keep trading away pieces to get a response. It has never worked. The stats show that liberal churches decline and die, and that churches that actually believe things that are countercultural are the churches that grow.”

Brighton

I decide to get in touch with evangelical congregations in Brighton. Of all the churches in the UK, surely they might provide some examples of how to hold a traditional perspective on sexuality and best reach out to the LGBT community?

To my surprise, the thriving evangelical church with which I have personal links and which I know has been open to speaking with journalists in the past ignores my request for an interview. Phone calls, emails and tweets are all met with radio silence. In a bid to speak to someone on the ground, I email seven other evangelical churches based in Brighton. Only three respond. One minister will speak to me, but wants reassurances about what will be published, another sends their responses via email only to rescind them a day later after the church’s trustees get wind they are speaking with a journalist and worry that jobs could be lost and reputations tarnished. Finally, Archie Coates, vicar of the HTB church plant St Peter’s says he’ll chat and “say what he can”.

St Peter’s has recently finished a three-part sermon series on relationships so I’m keen to know how they addressed same-sex love. To my surprise Coates tells me this topic wasn’t included in the talks that covered marriage, relationships at work and parent/child dynamics. When I press him on whether homosexuality has ever been preached about from the front on a Sunday, he says no. “I tend to use the pulpit, if that’s the right word, and preaching, primarily to help people in their identity in Christ – to affirm them as human beings and as children of God, that tends to be what I go after,” he explains.

When I ask him for St Peter’s theological position, he’s not keen to take sides. “Beyond sex being for marriage I try to not have a ‘St Peter’s view’ because we’re wanting people to be welcome and find their identity in Jesus…and then I have a confidence that the Holy Spirit is able to talk to people, and we’re on a journey, and all the rest of it.”

I ask him whether this approach could lead to confusion and hurt for gay people who may, later down the line, find there are barriers to serving in the church if they are in same-sex relationships. “I’d just like people to come in and find a relationship with Jesus and being gay is no barrier to that…I think the danger with the other approach is that actually you put a barrier up before people even have a chance to explore faith and the life of Jesus for themselves.”

For Christy Smith, the other Brighton pastor I speak with, it’s a question of feeling personally illequipped to speak about sexuality with confidence. He tells me he has covered the topic in the past when it was appropriate, but: “Because we’ve been so quiet, for us to get into that debate now, most of us are not equipped.” He tells me he worries about “gangs of protestors” potentially turning up outside the church and the “trial by media” that you see with Christians who put their heads above the parapet on issues of sexual ethics.

“The difficulty that we find in Brighton is that there’s a portion of the Church that would be very liberal and they would be very vocal. If we try even to discuss our beliefs, they are immediately: ‘Oh, you’re transphobic’ or ‘you’re homophobic’ or ‘you’re a bigot’.”

From speaking (and not speaking) to pastors in the UK about sexuality and the Church I’ve found that Christians are still fearful about broaching the subject, for a variety of reasons (many understandable). But wherever you stand on the theological debate, what’s clear to me is that silence isn’t a viable option for churches. Not for the Lizzie Lowes, whose lives literally depend on it; not for the David Bennetts who need support and love to live a radical life of discipleship; not for the Sarah Hagger-Holts and Jade Irwins who want to feel they can bring their whole selves (and families) to church; and not for those Christians and pastors who, now more than ever, are looking for the language to articulate their position in an increasingly hostile environment. Perhaps the Church could learn a thing or two from our brave gay and lesbian friends and find the courage to ‘come out’. There’s much at stake.