In the 14 years since I began my faith discussion show Unbelievable?, I’ve never witnessed a conversation quite like the one that took place in front of a 1,000-strong audience at Calvary Chapel Costa Mesa, California.

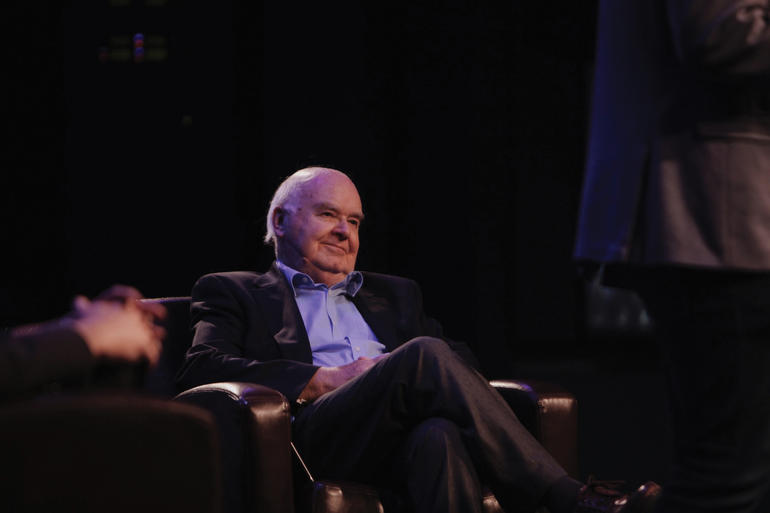

I had invited John Lennox and Dave Rubin to join me for a live recording of The Big Conversation video series, in which Christians and atheists debate big questions about science, faith and philosophy.

Lennox is a longstanding Christian thinker whose background as an Oxford professor of mathematics has seen him debate high-profile atheists such as Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. Rubin is a rising star in the online world, regularly sitting down with various public intellectuals to debate culture, politics and – with increasing frequency – religion. His YouTube channel The Rubin Report has more than 1 million subscribers.

Lennox has often spoken and written about his own Christian convictions and why he holds them. What made this conversation unique was that Rubin’s views on religion are in a state of flux.

At one time he looked like a typical US Millennial. He had grown up in a culturally Jewish household but, as a gay, secular liberal, he adopted the atheist outlook of many of his peers. A turnaround in his political views occurred in his mid-30s, however, as he began to question the so-called progressive left-wing ideology and its effects on free speech. Rubin is now counted as a leading conservative voice in America’s culture wars. But could his political conversion be followed by a religious one?

Repeatedly the name of one particular spiritual mentor came up in our conversation: Jordan Peterson, author of the best-selling book12 Rules For Life (Allen Lane). Rubin undertook a 100-city book tour with the Canadian psychologist and, like the legion of fans who turned out to see Peterson, has been deeply influenced by his lectures on meaning and faith.

All of this opened the door to a remarkably honest dialogue with Lennox, discussing whether this generation’s crisis of meaning could lead to a renaissance of Christian faith. There was plenty of humour as the YouTube host frequently joked about being the object of an evangelistic campaign taking place live on stage. Yet, many a true word is spoken in jest. As Rubin himself remarked: “There has to be something outside of us, or the rest of this makes no sense.”

JB: Dave, until recently you called yourself an atheist, but is that not the case any more?

DR: I had a bunch of high-profile atheists on the show in a row, and then people online kept saying that I was an atheist. And then I sort of just said it one day too. It didn’t mean anything to me one way or another. Then two years ago I spent a time of retreat ‘off-grid’. One of the thoughts that I kept having in my peace was that: I’m not an atheist. I came back to the show and said in a very casual way that I just don’t like the word ‘atheist’ – it doesn’t fit with what I believe. I do believe in something else, even if I can’t completely articulate what it is. And I got a lot of hate for that one!

JB: John, you grew up in a Christian family. How was faith presented to you?

JL: I grew up in Northern Ireland, which isn’t always the best start to discussing religion! However, my first encounter with Christianity was not mind-closing; it was mind-expanding. I remember when I was about 13, my father gave me Marx’s Das Kapital. I said: “Dad, have you read it?” He said: “No.” “So why should I read it?” “Because you need to know what other people think.”

My parents’ Christianity was morally credible – they actually lived what they believed. It was noticeable when I went to Cambridge university in 1962 that for many of my contemporaries from Ireland, the moment they got out of the country was the end of any Christianity because they’d never made it their own. They’d never thought about it. But I’d been encouraged to think about it, and that set the compass bearing.

JB: Nietzsche famously declared that “God is dead” 150 years ago. How is our increasingly post-Christian culture affecting today’s generation?

DR: I’ve found that, at a micro-level, you can be a non-believer and be absolutely moral and a productive member of society. What I think is becoming the problem is that societies can’t organise around that. That is a hard thing for me to say, as someone whose beliefs are rooted in science and the Enlightenment.

Yet nowadays, when you have to admit that there are more than two genders and all of these things… we know what facts are. And yet, because this has become untethered to anything other than how you feel, everything is up for grabs. That’s why it feels like there is something sort of godless happening here.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that, generally, believers right now are more tolerant. Who are the most intolerant people in society right now? It’s the people who are constantly telling you how tolerant they are; that’s the irony – it’s the people that tell you you’re a bunch of racists and bigots and homophobes. And that’s the real bizarre flip that we have happening in society, and I think that is linked to a post-Christian world.

JL: Nietzsche was a very accurate prophet. He could see what many contemporary atheists cannot see – that if you abolish God, you remove any solidity on which you can base the morality of human dignity and freedom. He saw that connection. He said if you get rid of God, you have no right in the end to values.

DR: I think the documents of the USA are the greatest man-written political documents. And what did the founders say? They said these are God-given rights; they’re self-evident– the right of freedom and of free speech. We can protect these things, but we didn’t give them to you, because they came from somewhere else.

But there is such a bizarre assault on freedom of speech right now, and it comes mostly from the secular world. Even as someone that saw this coming, it’s gotten so crazy that I’m still a little surprised myself.

JL: I think people are longing for sense. Although they often don’t believe it or have never even heard of it, they are made in the image of God; they’re beings who’ve got eternity in their hearts. And a materialist universe without meaning just won’t satisfy them, because they’re actually made for something bigger. As CS Lewis put it years ago: “If you find a longing in you that’s not satisfied in this world, maybe there is another world in which it could be satisfied.”

DR: As I’ve sat down with believers and non-believers, I’ve genuinely found the believers not only more welcoming – but more open, actually happier; less dependent on things outside of themselves – more self-reliant. I don’t think that means I’m going to be religious per se tomorrow. But, I have no problem with Jesus – I like the guy. The message of Jesus – I love these ideas.

JB: Dave, have you been rediscovering the religious roots of your own Jewish background?

DR: My parents live in New York in the same family home that I grew up in, and I went to the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah – the beginning of the Jewish new year. You have the week or so between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur where you’re supposed to think about your life, the good things that you’ve done, the bad things – you apologise to people, whoever you may have done harm to. And I really did that this year. I probably did drop the ball a couple of times on Twitter! But I really was very aware of that and I tried.

JL: I’m not Jewish by background, but I owe everything to a Jew, and the history of the Jews has been enormously important to me. I’ve been in Auschwitz many times and I’ve wept every time. I’ve many Jewish friends who lost everybody, and that raises huge, deep existential questions.

I see the Jewish history – the history of Israel, the Law and the Prophets – as pointing towards something big. I’ve many Orthodox friends who still expect HaMashiach– the Messiah – to come. Of course, the difference is that I believe hehas come.

I find Yom Kippur moving, because I see Jesus as the fulfilment of it. The ‘sin’ word is not popular these days, but it seems to me that there’s a fulfilment within what Jesus did and taught – a powerful fulfilment of everything that Judaism stood for and stands for.

DR: You know, just a few days ago at that service I was trying to be cognisant that it doesn’t necessarily matter if I believe in all of it fully, but there is value in this. This story that has been told by my parents and my grandparents and my great-grandparents, going way back when.

There must have been something that kept this thing alive, and there must have been some reason behind it. For me to pretend that I’m so enlightened that I could just set all that aside...that strikes me as the worst sort of ego-maniacal hubris.

JB: But many atheists say that religious beliefs amount to little more than superstition now that we have science...

JL: I am a scientist. And one of the fascinating things is that science is a direct legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” [Genesis 1:1]. The Hebrew Bible, written millennia ago, knew there was a beginning. It was the early 1960s before scientists caught up with that.

The early pioneers of modern science – Galileo and Kepler and Newton – they were all believers in God. I’m not remotely ashamed of being a scientist and a Christian, because I want to argue that it is Christianity that gave me my subject. And CS Lewis put it brilliantly, he said: “Men became scientific because they expected law in nature, and they expected law in nature because they believed in a lawgiver.”

So I think that in the 21st Century, we can push back on that very naïve notion: that God’s out – that we do science now. No! Science actually brings God back in.

JB: Where does this leave you on the God question, Dave?

DR: I think there’s a utility in believing in something outside of myself. So if you want to call that ‘God’ – that there is something outside of me, there is something that is connecting all of us, that has nothing to do with the material world, there is something that drives us, that is the driver of humanity, that is something good – I believe that.

JB: Would you put a name on that ‘something’?

DR: Erm...Jesus?! (laughs)

JB: But how does the sense that there is something beyond yourself make a difference?

DR: I respect the question, truly. And it’s the question. I would say I’m on the adventure to finding that out, and I’m really OK with that. I hope that doesn’t sound dismissive of the question or like I’m trying to evade it – I’m really not.

JB: Sounds like we’re not going to convert him tonight, John!

DR: You’re doing your best! You’re working overtime over there, I’ll tell you that much!

JL: Could it be that that ‘something’ is actually personal? Now, your Hebrew scriptures would say exactly so, because that’s how Bereshit/Genesis starts – with a God who sees, who blesses, who speaks. If this is true then God is interested in me, and he is wanting me as a discussion partner –he’s wanting to talk to me.

It’s worth testing the claim at least, because it runs right through the whole of the Hebrew scripture and the New Testament; that’s the fundamental thing – he’s a speaking God, not dead.

JB: Dave, do you think it’s possible that there could be a God who is personally interested in you?

DR: If he walks out on stage right now, I will get baptised tomorrow! My basic answer would be yes – why would I rule that out? When I joined Jordan Peterson on his book tour we were in the UK and a couple came up to me before the show, and they both looked very distraught. They were maybe in their late 20s or early 30s – and the guy had just found out that he had stage four cancer, and he didn’t have much time to live. The woman was a few months pregnant, and the foetus had died, and she was going to have to have it removed the next day. Unimaginably horrific circumstances.

The only thing I could say was: “God bless you.” That’s what I said. There was just nothing else I could say.

JB: John, do you want Dave to become a Christian? I’m guessing the answer is “yes”?

JL: You’re not guessing! Because I’ve experienced a life which I don’t deserve, which has been full of profound joy; a journey that has been deeply meaningful to me, and it’s connected with my relationship with Christ – of course. Of course, my desire is that, not only Dave, but everybody, can share the experience that I share and become Christians.

But I’m not in the business of browbeating people and forcing them beyond where they are. That’s why I believe in public discussion – let’s have the discussion on the table from different points of view, but trust the people to make up their own minds.

So my motivation is to get the message out and leave the results with God. So of course that’s my desire. But don’t specify Dave alone, poor chap!

DR: Thank you, John!

This is an edited extract of The Big Conversation between John Lennox and Dave Rubin. Watch in full at thebigconversation.show