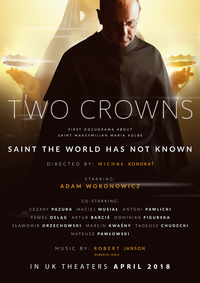

I never thought the day would arrive when I would draw parallels between Elon Musk and a Catholic saint. But that’s exactly what happened as I settled in to watch Two Crowns, the new film about Father Maximilian Kolbe, otherwise known as the “saint the world has not known”.

Among the many features of an extraordinary life — as movingly told in this 92-minute film which is on release at 24 Odeon theatres throughout the UK in April — was his design of a spaceship. This was in 1918 and the drawings contained exceptional detail and vision. Like Musk, the billionaire entrepreneur set on making humanity a multi-planetary species, Kolbe had a brilliant mind and unwavering faith in humanity to innovate and create.

For Kolbe, though, reaching space was “to watch God’s work from there”. It is here the similarities between he and Musk begin to fade, because as the film progresses and Kolbe’s life unfolds, it wasn’t his ability to push the boundaries of human ability and intellect that leave the profoundest mark on the viewer, it was his capacity to love.

This love was most obviously displayed in Kolbe's death. In May 1941 Kolbe was sent to Auschwitz. In the cruelest of conditions he shone brightly, culminating in the day when ten prisoners from Kolbe’s block were selected for death by starvation. Kolbe was spared. But, to everyone’s surprise, not least the commanding officer, he stepped out to make the costliest of offers — his life for another.

“What have you chosen?”

Comprising interviews, drama and a fascinating selection of archive material, Two Crowns begins with a young Kolbe having a vision. We then see him sharing this with his mother, explaining that it involved the Virgin Mary giving him a choice between a white or a red crown. “White means purity. Red martyrdom,” he says, to which his mother asks, increasingly concerned: “What have you chosen?” Kolbe’s answer gives the film a sombre yet captivating opening.

Filming for Two Crowns took place in Poland, Italy and Japan, three places where Kolbe’s remarkable legacy lives on to this day. It’s well produced, includes some lovely cinematography, and is carried along by a gentle, understated score. It’s filmed in Polish with English subtitles.

Character, humour and surprise

One of the notable features of Two Crowns is the way it excellently captures Kolbe’s restlessness to bring good to the world, so much so that there were points when I felt almost breathless trying to keep up with his work — from the creation of a monthly magazine in the wake of threats against the Catholic Church by Freemasons in 1917, to the founding of Niepokalanów in 1927, a monastery and publishing house near Warsaw.

The many contributions reveal different insights in Kolbe. “He did not talk much,” one reveals. “He didn’t have a special gift of speaking due to health issues. Yet thanks to his calmness, ability to listen, through asking the right questions and encouraging thinking, which were suggested gently and subtly, the spirit infected the people Kolbe talked to.”

There are also lovely moments of humour. “You keep laughing at me!” he tells his students, at which point the film pauses and gently breaks away to another interview. It’s fittingly done, prompting the viewer to ponder how the words epitomise the way many of his ideas were greeted by others. But, in his own unique, loving way, he always seemed to have the last laugh.

It is striking watching the film how Kolbe sought to make the most of every opportunity and resource available to do good and further the faith that was so dear to him. There is much to learn from him.

Controversy and celebration

In 1998 a statue of Father Maximilian Kolbe was placed alongside ten martyrs of the 20th century above the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. It caused a stir in the Catholic Church, with some arguing that Kolbe was not a martyr since his death was the result of an act of love not odium fidei (hatred of the faith).

It’s sad that the dispute exists because it detracts a little from Kolbe’s heroic, faithful life. In a similar way, many of us may approach the film distracted, even put off completely, by its Catholic bent. I certainly sat uneasy on occasion.

And yet, as the film closed with a powerful portrayal of Kolbe’s final moments, all questions and concerns had disappeared. Instead I was left humbled and silenced by a man of extraordinary love. And with that I was reminded of another man who also sacrificed his life — not for one, but the many. Jesus Christ.

This is where the power of the film ultimately lies. For that Two Crowns — and more importantly Kolbe himself — should be celebrated.

Tim Bechervaise works full-time in the finance industry. He attends Discovery Church in Swindon and likes to dabble in the occasional bit of writing

Click here for a list of UK cinemas who are screening Two Crowns

Click here for a free sample copy of Premier Christianity magazine