In July 2018 children at a primary school in Croydon were prevented from opting out of a pride event their parents felt conflicted with their religious views. In 2016 an experienced nurse, Sarah Kuteh, was dismissed after she spoke to her patients about her faith and gave one a Bible.

In October 2006 Nadia Eweida, a Christian employee of British Airways, was asked to cover up her cross and was placed on unpaid leave when she refused to do so. Last month, street preacher Oluwole Ilesanmi was arrested outside a tube station in London for “breach of the peace” while sharing the gospel.

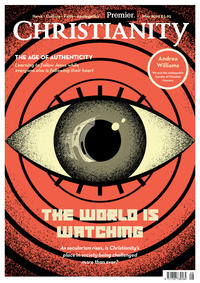

These are just some of the cases that have been highlighted in the media in recent years involving Christians and their right to express their faith. Some of the examples, such as that of Eweida, were fought and won through the courts, while others are still being contested. Many Christians feel there is a growing hostility in Britain towards its religious foundations; some are less sure about sharing their faith with friends and colleagues as a result. As demographics change and Britain as a whole becomes less Christian, do these cases indicate a growing secularism in society resulting in a chilling effect on religious freedom, or are Christians just struggling to accept their faith is losing the place of privilege it once held?

Intolerant secularism

Dr Sharon James is a social policy analyst at the Christian Institute (CI), an organisation set up to promote and defend Christian beliefs in Britain. The not-for-profit charity campaigns on issues of free speech and provides legal support for Christians defending their positions in court. In recent years the CI has won Supreme Court victories in cases such as Ashers, where Christian bakers were accused of discrimination for refusing to make a cake bearing a pro-gay marriage slogan, and has been successful in challenging the ‘Named Person’ proposals brought forward by the Scottish government in 2016. These laws would have allocated every child in the country a State guardian whom the child could speak to away from his/her parents. The guardian, a teacher or health visitor, could share the disclosed information with third parties. Supporters of the new law say it will ensure more cases of child abuse are uncovered; critics argue it will stretch resources for genuinely vulnerable children and that it permits the State unlimited access to private, family life, which is protected under the European Convention of Human Rights.

When I call to ask her about secularism and changing trends over the last decade, Dr James tells me that “intolerant secularism” among a small but “hard core” group is gaining traction in the UK, with one of the main battle grounds being education. “There seems to be what I would call a hard secularism,” she explains, “and the way that is manifesting itself is that, when we come to the schools’ issue, parents are being told at the moment: ‘Of course, we believe in freedom, so of course you can believe what you want in the confines of your home, but you know what, when your children get into school we, the State, have the right to re-educate them, and we are going to re-educate them according to our secular values.’ Now, that is not a tolerant secularism that is a very intolerant secularism and it’s effectively threatening the privacy of the family, as well as freedom of religion and conscience.”

"Some are trying to imply that if you disagree with somebody's belief or lifestyle, you hate them"

The “re-education” James refers to is changes to curricula, such as recent government proposals to introduce Relationships Education to primary-aged children from 2020. According to the Department for Education, the new law makes it compulsory to teach young children about relationships “of all kinds”. Supporters of the initiative say it helps children understand the different family dynamics that exist in the modern world – be that single-parent families, lesbian and gay partnerships or heterosexual marriage. Critics argue that primary school children are too young to be taught about complex relationships parents should be explaining at home. They also want the right to withdraw their children from lessons they feel are inappropriate.

James says that on the surface Relationships Education seems to be a good development. Among some of its aims are: educating young children about staying safe online and encouraging self-care and positive mental health. But, she says, it could be used by some as a “Trojan horse”, hiding what she describes as a “transgender ideology”. According to James, some schools have already started showing children as young as four short films about discovering their “real gender identity”.

“The majority of people, parents of goodwill in this country, whether or not they’ve got any faith at all, are uncomfortable about teaching five-year-olds that they can choose whether to be girls or boys or something else,” she says, adding: “We’re sure that many teachers will do it in an appropriate way, but we’re concerned to protect the children whose teachers won’t do it in an appropriate way.”

Recently there have been weekly parent protests outside schools in Birmingham and Manchester over a similar issue: the introduction of LGBT rights lessons. Hundreds of Muslim children were withdrawn from classes at Parkfield Community School in Saltley after parents deemed the content age-inappropriate and undermining to their rights and responsibilities as parents.

James claims there is an “intolerant view” among a small group within Ofsted that parents holding traditional values, around sexuality in particular, need reeducating. “…British values has been interpreted by some in Ofsted as respecting the beliefs and lifestyles of all people. Now I can respect a person while disagreeing with their belief and lifestyle, and that’s a distinction that is actually legally there, but some people are trying to imply that if you disagree with somebody’s belief or lifestyle, you hate them.”

James says it’s the job of every Christian to remain vigilant about small legislative changes because they can seem innocuous but lead to greater State monitoring and further constraints for Christians. “A small legislative change would be withdrawing the right of parental withdrawal for Relationship Education,” she explains, which has just been voted through in the Commons. “That seems tiny and so innocent that most people go along with it and can’t see the dangers. But, we see the dangers of that, because then it’s the next thing. And then it’s the next thing. Then you take away the right of parents to home educate. And then you say: ‘OK, we will send State officials in to interview children. And if they say that certain things are right and certain things are wrong, we would say that their integrity is being threatened because they aren’t allowed by their parents to live out that lifestyle if they want to, so we will remove them for their own safety.’”

The common good

Not every Christian takes the same view of creeping secularism and State interference as James. Paul Bickley, a research fellow at the think tank Theos, which exists to stimulate debate about the place of religion in society, presents the narrative quite differently. “When Theos launched in 2006 Richard Dawkins had just published The God Delusion (Black Swan) and that was selling millions of copies. Discourse like that was really strong in the public square, and it was aggressively anti-Christian. In fact, anti-Muslim as well. The idea of religion as a virus or something inherently irrational or inherently abusive, or ridiculous even, and that people of faith should not hold positions of public authority, or if they did they should be very, very qualified about how public they were about it.” He says that those prominent voices have mostly subsided, partly due to loss of reputation and partly because one of the best known of the ‘New Atheists’ – Christopher Hitchens – passed away. For Bickley this doesn’t mean all threats to Christianity have ended, but the context has certainly changed. He says Christians in the medical profession have found “conscience exemptions being eroded” and that campaigning by secular groups such as Humanists UK is becoming more effective and influential. But, he says: “We don’t necessarily see it as a zero sum game”, where increased secularism means life is worse for Christians.

Bickley argues that the recession has provided an opportunity for Christians to contribute to public life in a meaningful way that is increasingly being recognised by the State. “Pick any local authority in the country, particularly the ones already struggling, and you will see they’ll have lost at least a third, up to 40 per cent, of their funding from central government,” he says. “Therefore, on a local level, faith groups of whatever kind, but mainly Christian churches, doing good stuff, has become increasingly important. Leaders in local authorities recognise that, national politicians recognise that, and I think, therefore, some of the stuff which was about keeping churches out of that kind of business, they’ve just had to drop it.”

When I put this to James, she agrees on one level that the sheer amount of Christian social action is as high as it was in its heyday in the 19th Century, but, she says, there is a flip side to this argument. “When you look at how those Christian organisations are able to conduct their work, increasingly there is pressure on them not to be upfront about their Christianity as they do it. Their capacity to give out tracts or say grace before meals [is limited]…

“We would say loving neighbour also means that you can preach the gospel to them, because they do need to know about Jesus; and it’s that upfront ability to preach the gospel openly that has been challenged.”

The secular perspective

When I call to speak with Richy Thompson, director of public affairs and policy at Humanists UK, I’m expecting a combative conversation. After all, the organisation he works for supports many of the issues Christian groups would vehemently oppose. It is currently campaigning against faith schools, for laws that will enable sick people to end their own lives and to legalise humanist marriage in England and Wales. To my surprise Thompson is mildmannered, thoughtful but also pragmatic. His view is simple: in an increasingly secular society, where latest polling shows more than half of the country has no religion, religious privilege makes less and less sense. He says given the demographic shifts it seems increasingly likely that public policy and the law will “try to rebalance things” to reflect the UK as a “a diverse state with people of all different religions and beliefs”.

Thompson uses words such as “inclusive” and “equality” to describe the position of Humanists UK. He believes that people with no religious views should have just the same rights in society as those with faith – a sentiment most Christians would agree with. There are also other areas of common ground. Humanists campaign against blasphemy laws in countries such as Pakistan, where Christians have been held on death row for years for minor infractions against Islam. They also support people who have been abused in coercive religions in the UK and help atheist asylum seekers requesting refuge from countries with authoritarian theocracies.

Support for their cause is undeniably growing. In recent years the organisation has quadrupled in size and income; it now boasts 75,000 members and supporters. In Scotland in 2017 they conducted more humanist weddings than any religious body, including the Church of Scotland. The All-Party Parliamentary Humanists Group has also swelled to over 100 MPs and Peers and they’ve had several campaigning successes, among them: humanist marriages in Northern Ireland being made legal, the first humanist recruited to lead a chaplaincy team in the NHS and the Welsh Government changing its law to teach non-religious views alongside religious ones.

"There's a big difference between advocating for equality and preventing Christians from expressing their beliefs."

When I ask him the secret behind its success, he says it comes down to growing support for its campaigns, even among religious people. “We best represent the view of the public on all the public affairs issues we work on. And that, I think, and the ongoing visibility of our work, whether it be campaigns or increasingly reaching out into different areas of people’s lives, like ceremonies or pastoral support, or elsewhere through our events programme, does mean that people are finding us for the first time.”

When I ask him whether they face animosity from faith groups at all, he tells me that the area that tends to spark the most disagreement is, perhaps unsurprisingly, faith schools. On one side of the argument there are Christians – and particularly Catholics, who run 10 per cent of all schools in England – who say parents have a right, and even duty, to bring their children up in the Christian faith and shouldn’t be prohibited from doing so. On the other side, secularists say that taxpayer-funded schools should not be beholden to the religious views of one group.

In 2018, after a protest outside parliament and a sustained campaign urging supporters to contact their MPs, secularists won a partial victory when education secretary Damian Hinds announced that the government’s 50 per cent admissions cap, which stopped faith schools having full control over their admissions policy, would remain in place. It was a partial victory because, in the same announcement, Hinds also said there would be an increase in voluntary-aided faith schools, which are allowed to select 100 per cent of pupils based on faith. The Catholic Church, which has been educating children since before the State system existed, and which effectively gifts the State its land and buildings as part of their historic relationship, has stopped building new schools that continue to be subject to the cap. The tug of war continues.

When I speak with Chris Sloggett, campaigns and communications officer at the National Secular Society (NSS) he is less forthcoming than Thompson about the organisation’s membership numbers. He tells me he doesn’t know the “exact detail” and later sends a quote via email that positions the organisation in direct relation to religious groups: “We remain a small organisation which doesn’t have anything like the resources which organised religious groups do. But we like to think we punch above our weight.” What he will say on the record is that they’re working on increasing their influence in parliament and with the public, and that polling suggests the majority of people are behind the issues they care about.

In essence the NSS is concerned with religion being imposed on others. It thinks “freedom from religion” is as important as “freedom of religion” and campaign for a complete separation of Church and State. Sloggett’s argument is that Christianity in particular has “entrenched privileges” that are out of step with a modern world. He sees the Anglican bishops in the Lords as something to “tackle” and certain religious voices as “intolerant”. When I ask him whether they will ever achieve their goal, he says the sign would be “the disestablishment of the Church” so that there isn’t “an automatic right for 26 bishops to sit in the House of Lords”. A report published by NSS suggests a key moment to make its move would be the ascension of Prince Charles to the throne. “It’s likely to be a moment when our constitutional settlement comes up for question,” he explains. “Prince Charles becoming king is going to throw everything up in the air, if you like…when 52–53 per cent of the public is saying they don’t have a religion, it’s going to be quite difficult to sustain the argument that Prince Charles should swear an oath to protect the Church of England’s privileges when he becomes king.”

Common ground

When you start to consider the perspective of people who work for, or campaign with, organisations like Humanists UK or the National Secular Society, you realise just how much ground Christianity still holds, in terms of influence in parliament and in the realm of education. In an increasingly multicultural and multifaith world, should religion – and specifically Christianity – be endowed with special privilege and importance? Many would say “yes”: that the rights and freedoms we all benefit from in the UK came about precisely because Christianity was part of the fabric of society; that we owe a vast amount to Christian principles of the innate worth and dignity of the individual and that removing this foundation could have serious ramifications for everyone. Others argue that as Britain becomes less and less religious, our institutions should reflect the views of the people. These are significant questions for the whole of society to grapple with.

The view of secular organisations that people should have freedom from religion is a noble one based on compassion and a deep sense of justice. But there’s a big difference between advocating for equality for all and people of faith being prevented from expressing their beliefs or holding positions of influence. Cast your mind back to 2017 when the former leader of the Liberal Democrats, Tim Farron, was arguably forced out of office following intense media scrutiny of his Christian beliefs on sexuality. In his resignation speech he said that despite believing strongly that Christianity should never be imposed on others, he had become “the subject of suspicion”, adding, “in which case we are kidding ourselves if we yet think we are living in a tolerant, liberal society”.

Many Christians worry that secularism, rather than bestowing freedom, threatens to take rights away. Thompson assures me that the kind of society he’s espousing would make it “very possible” to come up with a “secular settlement” that doesn’t restrict the rights of faith communities, but he concedes that there isn’t currently a “perfect model” out there.

When I ask James whether she thinks it’s possible to have secularism that works for everyone, she says today’s hard secularism “sees Christian morality as repressive and toxic.”

“That’s not something that they want to tolerate. They believe that to teach children Christian morality is evil, harmful and oppressive.

“I would just remind you that the track record of atheist governments in the 20th Century was not glorious. You could easily just Google the figures of Christians and other faiths who were killed in Communist Russia, Communist China, Cambodia…Atheistic governments have been brutal in repressing faith, and at first they say: ‘Oh, toleration, toleration, toleration’, but it doesn’t last very long.”

Whether or not you think organisations like Humanists UK and the National Secular Society represent the kind of “hard secularism” James is warning against, ultimately it comes down to this question: can you have a truly democratic country that respects the rights of everyone to hold and express their beliefs, while keeping both fundamentalist religion and fundamentalist secularism at bay? Thompson’s admission that a perfect model of a secular State has not yet been found is telling. Until then, Christians would do well to be on their guard.