No one had ever been to the North Pole before. For years explorers had dreamed of being the first to arrive at the top of the world, a place as alluring and foreign as an unexplored planet. Mapmakers knew about the Pole: it was the spot on the globe where any movement in any direction would be to the south, and where all the time zones of the world mysteriously converged, but no one knew what it was like.

Lieutenant George De Long set out with a crew in 1879 on the USS Jeannette in hope of claiming the North Pole for the United States. Historian Hampton Sides records the story of this expedition in his book In the Kingdom of Ice (Oneworld). Sides’ account shows that De Long’s plans were based on the idea there was an “open polar sea”, which could be smoothly sailed through in the summer months. The idea of this shallow, warm and ice-free body of water around the North Pole was widely accepted by cartographers, geographers and scientists at the time. Grandiose visions of economic prosperity bolstered the idea of an open polar sea. Those who financed these expeditions wanted the sea to exist. They hoped to profit from its discovery. Unfortunately, every previous expedition that had sailed north in search of this sea had run into a problem – ice.

Now, you might think that running into ice would lead scientists to abandon the theory of an open polar sea. Not so. Instead, the theory was modified and the idea of a “thermometric gateway” was added. Sides explains: “This Arctic ice barrier was merely a ring that encircled the large warm-water basin…If an explorer could burst through this icy circle, preferably in a ship with a reinforced hull, he would eventually find open water and enjoy smooth sailing to the North Pole.”

De Long, and the 28 men who signed up to be part of his crew, desperately wanted to find that portal. But as he encountered ice that seemed to stretch out forever, De Long slowly realised that all the experts had been wrong. De Long and his crew were forced to come to terms with the fact they’d been duped.

In September 1879, the USS Jeannette got trapped in an ice pack. It drifted for nearly two years, until finally the shifting ice crushed the ship and sank it. De Long and his crew escaped and tried to venture towards Siberia. Some made it, but De Long died of starvation in late October 1881. His body was covered by the snow, except for one of his arms, which was raised as if to signal towards the sky.

The story of the USS Jeannette is inspiring yet tragic. We admire the courage of De Long and his crew, and we also pity them. The map they had of the North Pole – their idea of what the world was like – was wrong, disastrously so. And in the end they planned an expedition and staked their lives on something that turned out to be false. The mythical map they trusted cost them everything.

Faulty Maps

Just as we use maps or GPS navigation to travel to a destination, we also have maps in our mind about where we are going in life, what the point of everything is or what we need to make us happy and fulfilled. That’s why we sometimes describe events or seasons of life as being ‘mapped out’. We turn to the language of maps because we see our lives as a journey, a story with a beginning and an end, and we see ourselves en route towards a destination, pursuing joy and happiness.

But what happens when we pick up the wrong map for our journey through life? What happens when, like the men in De Long’s expedition, our map is mythical and fails to do justice to the way the world truly is?

The mythical map they trusted cost them everything

“Our culture often sells us faulty, fantastical maps of ‘the good life’ that paint alluring pictures that draw us toward them,” writes Christian philosopher James KA Smith. “All too often we stake the expedition of our lives on them, setting sail toward them with every sheet hoisted. And we do so without thinking about it because these maps work on our imagination.”

If we are to be faithful Christians in our time we must consider the primary maps that give direction to people in our world, maps that work on our imaginations by laying out a vision of the future and the road to happiness. What is the point of everything? Why are we on the earth? What does “the good life” look like? What will make me happy?

The pursuit of happiness

A few years ago Gretchen Rubin, a 30-something wife and mother, was experiencing a mid-life malaise. “I had everything I could possibly want,” she writes, “yet I was failing to appreciate it.” Rubin decided to embark on a “happiness project”. She identified what brought joy and satisfaction and noted what made her feel guilty, angry or remorseful. Then, she put together a concrete action plan filled with resolutions that would boost her happiness. The process seemed simple, but she soon ran into multiple paradoxes. “I wanted to change myself but accept myself,” she writes. “I wanted to take myself less seriously – and also more seriously. I wanted to use my time well, but I also wanted to wander, to play, to read at whim.”

At the beginning of her happiness project, she crafted twelve personal commandments to help her on the journey. The first three were: “Be Gretchen”, “Let it go” and “Act the way I want to feel”.

For Rubin, and for many in the West today, the purpose of life is to discover what makes you feel happy, live the life that is ‘right’ for you, and find whatever tools you need to make it to your destination. ‘Being yourself’ is the greatest commandment and, therefore, the greatest failure (some might even say ‘sin’) would be to sacrifice your own desires or dreams in order to gain someone else’s approval or conform to someone else’s view for your life.

It’s clear from her writing that religious experience is important to Rubin, but only because it is one of the ways she can pursue fulfilment and happiness. She never asks the question: which religion might be true? She only looks to religion to find what might be useful.

84 per cent of Americans believe enjoying yourself is the highest goal of life

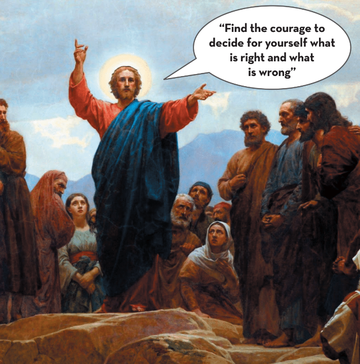

For many people today, all of this is just common sense. When the American comedian and TV host Stephen Colbert addressed graduates of Wake Forest University, North Carolina, he said that the best way to withstand criticism is to have your own standards so you can judge yourself as successful even if other people think you are a failure. Colbert ended his speech by encouraging students to “find the courage to decide for yourself what is right and what is wrong” and then to “make the world good according to your standards”, no matter what others might think.

According to research from bestselling authors Gabe Lyons and David Kinnaman, 84 per cent of Americans believe “enjoying yourself is the highest goal of life”. When asked: “How do you enjoy yourself and find fulfilment?” 86 per cent said you’ve got to “pursue the things you desire most”. A massive 91 per cent affirmed the statement: “To find yourself, look within yourself.”

The philosopher Charles Taylor describes our era as an “age of authenticity”. It’s the understanding of life that says “each one of us has his/her own way of realising our humanity, and that it is important to find and live out one’s own, as against surrendering to conformity with a model imposed on us from outside, by society, or the previous generation, or religious or political authority”.

The message of Disney

Disney movies are a great example of this thinking. Watch how a fairy tale changes once it gets the Disney treatment. The story’s main details and plot lines may stay the same, but the Disney twist often makes the crux of the story a moral principle about discovering yourself. As long as you are true to yourself, all your dreams will come true. It’s why Ariel rebels against her father: she longs to be part of a world she wasn’t created for. It’s why Aladdin becomes the prince he once pretended to be, and why Mulan refuses to conform to her society’s expectations.

Disney movies (and most of the rip-offs) tell us again and again that the most important lesson in life is to discover yourself, be true to whatever it is you discover and then follow your heart wherever it leads.

But take note: this is what Westerners believe. It’s not how the rest of the world sees life. Mulan bombed in China. The animated film about a young Chinese girl who joined the army during the Sui Dynasty in place of her elderly father wasn’t received well in the country the story was based in. Although the creators of Mulan assembled a terrific Asian cast and sought to pay homage to Eastern influences, the movie flopped.

What happened? While thousands of little girls all across America were at home, singing Christina Aguilera’s ‘Reflection’ in the mirror, most Chinese viewers said: “No, thanks.” Many of the Chinese nicknamed the main character “Foreign Mulan”. No matter how ‘Chinese’ she appeared, Mulan showed, through her actions, that she was really a Westerner in disguise. She was much too individualistic in her thinking, not respectful enough of ancient authorities and her self-promoting ways stuck out in a Confucian culture where modesty and community are prioritised over self-assertion. The Disney version also showed Mulan fighting not only for her family’s glory but for her own as well – an idea at odds with much of Chinese culture. In Eastern cultures, your identity is something you receive, something you discern from the order of nature, or with the counsel of family, not something you create on your own.

While some thought Mulan was heroic for being true to herself no matter what anyone else thought, the Chinese thought Mulan was being selfish. What most Westerners saw as a virtue, Chinese viewers saw as a vice.

Your life's purpose

This Western map of authenticity is everywhere. It’s in songs about believing in yourself, following your dreams, looking inside to find the hero within or learning to love yourself. It’s in books where the main character casts off anything from the outside that pressures him or her into conformity. It’s even in some of our churches, where God is summoned to help us become whoever we really want to be.

We’re not going to be faithful to Christ if we just tweak the map here and there. We need another map. We need to know how to make our way forward in this world and how we can fulfil our ultimate purpose of bringing glory to God and finding satisfaction in him. We need the light of the gospel to shine on the mythical maps offered to us by our culture, so that we can see both the longings that we need to affirm and the lies we need to confront.

Your life purpose is not found by looking inside of yourself. Your life purpose is to know and love God. Any other purpose falls far short for our restless hearts. As Augustine said: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in you.”

The longing you experience to have the desires of your heart is right, but the lie is that your heart can tell you exactly what those desires are. Instead, we are to obey the words of the psalmist: “Delight yourself in the Lord, and he will give you the desires of your heart” (Psalm 37:4, ESV). Delight in God, and your desires will match his. And note the command: not “find yourself” but “delight yourself”. Note also the object: we are to find joy not in things but in the Lord.

Two options

Following Jesus in an era when everyone is following their hearts is difficult, partly because we think we must choose between either 1) embracing the dominant culture and being authentic and true to ourselves, or 2) rejecting the culture and instead conforming to constraints imposed by our society, families or even churches. Christians who want to affirm the good that exists in our culture will lean to the first option. They will redefine holiness and the pursuit of God so that they become tools to help you fulfil your deepest desires. “Just look inside your heart, ask everyone to affirm what you feel, be true to yourself and expect God to bless your authentic expression of your inner essence,” they say. Meanwhile, Christians who are on the hunt for the lies our culture tells us, will lean towards the second option. They think holiness means quashing your desires, denying your uniqueness and just following the rules without question.

So which is it? Should you live authentically by rebelling against the constraints imposed on you by others? Or should you live in conformity, by keeping the rules of an ordered, godly life? The answer is neither. True Christianity says: “No, thanks” to both options. In response to people who believe we should be “authentic” above all else, we say: “You don’t know yourself well enough to grasp your deepest desires, and even if you did, your desires are often wrong.” We need deliverance from many of our deepest instincts, not to celebrate them. And then in response to people who believe we should keep the rules and conform, we say: “Salvation does not come through a checklist of rules, as if by willpower we can manage our sin.”

Christianity combines authenticity and conformity in a most creative way. To be authentic, as a Christian, means I am to be true to the person Christ has named me, not the person I think I am inside. I am to live according to who God says I am – his redeemed child, a person remade in the image of Christ – and I now act in line with that identity. In our era it takes absolutely no courage to create and live by our own standards. True courage is not deciding for yourself what is right and wrong but seeking to discover what truly is right and wrong – for yourself and for everybody else. It takes courage to look outside yourself, to bind your heart to an ideal that is bigger than your own set of standards, to investigate truth rather than invent it.

Finding the truthful map

The first people to reach the North Pole were Frederick Cook and two Inuit men, Aapilak and Ittukusuk, on 21 April 1908. Unlike De Long, they didn’t try to sail there. They were well aware that there was no “open polar sea”. Instead, after an arduous journey across the ice, they arrived on foot, stocked with the provisions they needed to achieve their goal. Both De Long and Cook were brave and courageous, ready to persevere through the worst of circumstances. One crew made plans based on what they hoped to find, while the other took into account what was really there. There’s an important lesson for us here: you can be courageous yet still be wrong about the world. You can be brave yet perish. You can be a strong and determined person on a path to destruction. Sincerity, as good a quality as that may be, cannot ultimately save you. Your map might be wrong. “There is a way that seems right to a person, but its end is the way to death” (Proverbs 14:12, CSB).

Remember, you have been rescued from your fallenness, not affirmed in it. You are being remade in the image of God so that the ever-deepening discovery of his grace and goodness is the defining marker of your life, not your own self-discovery. You aren’t meant to be satisfied and happy with yourself as you are now; you’re embracing the vision of who God is making you to be!

The truly courageous are those who crucify the self the world tells us to be true to. But, thank God, we are then raised with Christ to become the person God always intended us to be. The greatest adventure we could imagine leads us to die to ourselves daily because it is only through putting our old self to death that we taste the reality of resurrection.

Trevin Wax is director for Bibles and Reference at LifeWay Christian Resources, and an author and teaching pastor based in Tennessee. To read more from Trevin on this subject, see his book This Is Our Time (B&H books). You can also hear Trevin interviewed on a past episode of The Profile podcast.