That culture has changed and is changing rapidly is news to no one. Christians, especially, will not be shocked. In decades past, politicians would have had to – at the very least – pay lip service to Christian values and tradition, but just last year the former leader of the Liberal Democrats, Tim Farron, was caught in a media dust-up after expressing traditional Christian views on gay sex. He resigned as party leader because, he said, “remaining faithful to Christ” was incompatible with effectiveness in that role.

This was seen by many as a victory for the progressive ideals of an open and inclusive society. But as Farron later remarked: “I seem to be the subject of suspicion because of what I believe…In which case we are kidding ourselves if we think we yet live in a tolerant, liberal society.”

Digital Babylon

The world has changed. But in what ways? How much? And by what measure can we gauge the differences?

As researchers at Barna Group, we have been asking questions like these for more than 30 years. Our goal is to help Christians understand the times and know how best to respond. We’ve adopted a phrase to describe our accelerated, complex culture: digital Babylon.

Ancient Babylon was the pagan, hyper-stimulated, multicultural, imperial crossroads that became the unwilling home of Judean exiles, including the prophet Daniel, in the sixth century BC. But digital Babylon is not a physical place, it is the pagan, hyper-stimulated, multicultural, imperial crossroads that is the virtual home of every person with an internet connection.

The Babylon of the Bible is characterised as a culture set against the purposes of God – a human society that glories in pride, power, prestige and pleasure. From the Tower of Babel, the “first city of man” in the book of Genesis, to the final act of God’s justice and restoration in Revelation, Babylon is both a place and an archetype of collective human pursuits set in opposition to God. The pages of scripture, and the pages of human history, are clear that there are times when faith is at the centre and times when faith is pushed to the margins. We are living today in a season characterised by the latter.

A post-Christian society

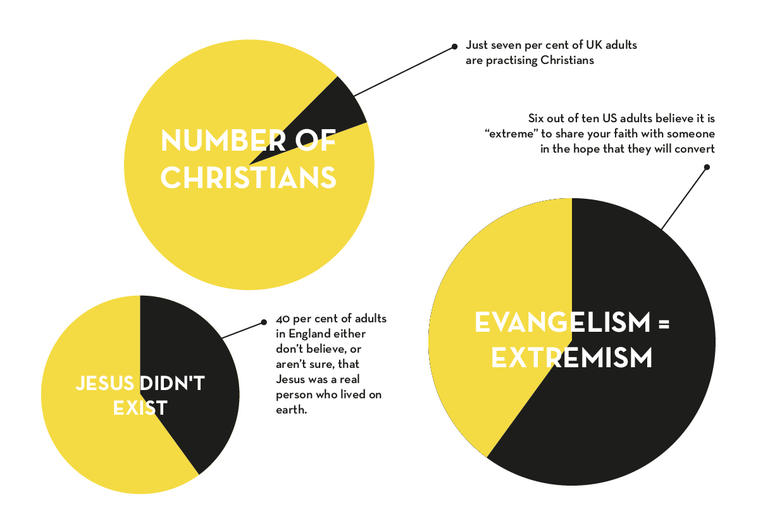

This shift – from faith at the centre to faith at the margins – is happening in the UK, North America and most other societies in the cultural West. Our data show widespread changes from a Christianised to a post Christian society. Just seven per cent of UK adults are practising Christians, meaning they pray and read the Bible at least weekly and attend church services at least monthly. In England, 22 per cent of adults and 27 per cent of youth believe Jesus Christ is a mythical or fictional character, rather than an actual person who existed in human history.

Loving those who don’t love you back is a radical act

When we conducted a major study on public perceptions of the Christian faith, the findings surprised us. The results, which were published in Good Faith: Being a Christian When Society Thinks You’re Irrelevant and Extreme (Baker) showed that six out of ten US adults believe it is “extreme” to share your faith with someone in the hope that they will convert. The figure was higher (eight out of ten) among atheists, agnostics and other religiously unaffiliated people.

We found similar sentiments among UK adults when we conducted the Talking Jesus study. More than half of non-Christians know someone who is a Christian, but 43 per cent of those who do are glad they do not share their friend’s faith. Six out of ten say they have no interest in knowing more about Jesus.

Some views are certainly based on negative personal experiences of evangelism, but overall cultural trends likely play a role too. Christianity is unappealing to many people because it runs counter to prevailing values and assumptions.

The new moral code

As the Christian faith has taken a cultural backseat, a new moral code has rushed in to fill the vacuum. We call it the “morality of self-fulfilment”, and it is characterised by adherence to six beliefs:

1. The best way to find yourself is by looking within yourself.

2. You should not criticise someone else’s life choices.

3. To be fulfilled in life, you should pursue the things you desire most

4. The highest goal in life is to enjoy it as much as possible.

5. People can believe whatever they want, as long as those beliefs don’t affect society.

6. Any kind of sexual expression between two consenting adults is acceptable.

Even a sizeable number of practising Christians – who prioritise their faith and are regular churchgoers – accept these nonbiblical views. This exposes an area of dangerous weakness in today’s Church. This grafting of cultural dogma onto Christian theology must stop. In order for Christians to flourish as God’s people, we must allow his moral order to rule our lives:

1. To find yourself, discover the truth outside yourself, in Jesus.

2. Loving others does not always mean staying silent.

3. Joy is found not in pursuing our own desires but in giving of ourselves to bless others.

4. The highest goal of life is to give glory to God.

5. God gives people the freedom to believe whatever they want, but those beliefs always affect society.

6. God designed boundaries for sex and sexuality in order for humans to flourish.

Good faith Christians

So how do we live in a world where our faith is increasingly categorised as extreme?

Our response must be grounded in an understanding of the Bible as the word of God with authority for our lives. If we truly believe this is the case, Christians can have confidence to live our convictions – even at the risk of standing out from the crowd. Our identity is not based on the perspectives of those around us, but rather on who the Bible says we are.

If we are confident in our faith, we can engage thoughtfully in some of the most divisive issues of our time. Rather than retreating, we can graciously provide a biblical response to those issues.

We define good faith Christians as people who are counter cultural in the following ways. Firstly, they make space for people who disagree: as religious conflicts spiral out of control and true extremists win converts and the news cycle, we must be ‘confident pluralists’. This requires that we concern ourselves with defending everyone’s religious liberty – which may feel uncomfortable for those who are used to Christianity holding a privileged place in society. But living at peace in a pluralist society – and, more importantly, Christ’s command to love our neighbours – demands that we defend each person’s right to live according to his or her conscience.

Good faith Christians admit their biases, see the image of God in others and build diverse friendships. How we engage in relationships says more about the truth of what we believe than all our well-argued apologetics, or carefully worded doctrinal statements.

The grafting of cultural dogma onto Christian theology must stop

Good faith Christians believe every human life – in every form, at every stage – matters. We must give voice to those yet to be born, respect and defend the dignity of people who are disabled and ensure life extends to its natural end.

Good faith Christians understand the relational consequences of sexual freedom and offer a better way. We believe Christian community – the household of God – is the only remedy for the relational and sexual sickness that has infected the culture. We must articulate a biblical vision of healthy sex and sexuality. And we must be willing to live out our love and belief in community with real people.

Good faith churches make disciples who bless the world. Growing inwardly with Christ and facing outward as his body is a powerful combination, as we found in a study of churches in Scotland. Barna identified nine factors that make a statistically significant difference between baseline (that is, maintaining or declining churches) and growing churches. Of the nine factors, four related to growing inward and four to facing outward. The ninth, praying, is both an inward and outward activity:

1. Teaching the Bible thoroughly

2. Fostering close Christian community.

3. Developing new leaders.

4. Leading with a team that has diverse skills and spiritual gifts.

5. Prioritising outreach by serving the poor and sharing faith.

6. Partnering with other churches and causes.

7. Being innovative for the sake of the gospel. 8. Focusing on receptive teenagers and young adults.

9. Praying specifically for living faithfully in a post-Christian culture.

An old problem

There’s no doubt we are living in a contested culture in unstable times. It is a real and present challenge to follow Jesus and live well in society. And, for a season, it may not be possible to do both. It may be that no matter how winsome and charitable Christians try to be, we may be met with derision and even exclusion from the public square.

But this is not new. It would have been familiar to God’s people living in exile under Babylonian rule 600 years before Christ, and to those under Roman rule in the earliest decades after his resurrection. They understood what it meant to live as the people of God in a culture that perceived their way of life to be extreme. What it took for them to be faithful was not a spasm of passion, but rather a long obedience in the same direction. Obedience to truth, obedience to holiness and obedience to love.

In many ways it was extreme. Loving those who don’t love you back is a radical act. But it is also the high and holy calling of the people of God. Good faith Christians love our neighbours, believe in the Holy Spirit’s power at work in God’s people and are faithful to his call to be agents of reconciliation.

David Kinnaman is author of UnChristian, You Lost Me and Good Faith (Baker). He is president of Barna Group, a leading research and communications company based in California

Gareth Russell is vice president for UK and Europe of Barna Global, based in London

Click here for a free sample copy of Premier Christianity magazine