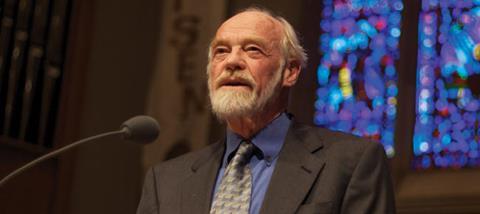

Eugene Peterson’s name has long been synonymous with one of the most famous modern translations of scripture. The Message was born after Dr Peterson was inspired to craft a translation to make the Bible come alive for his Presbyterian congregation. As a scholar of the biblical languages, Peterson was frustrated that his parishioners in Maryland couldn’t see how revolutionary the text was, during their Bible study classes. His answer was to translate the Bible with one question in mind: “If Isaiah or John were writing what they wrote for these people I am living with, how would they say it?"

Fifteen years later, The Message was completed and found its way into thousands of homes and churches across the Western world. One of those early readers was Bono – the lead singer of U2. The biggest rock star in the world heaped praise on Peterson’s work, describing it as “a great strength to me” in an interview with Rolling Stone back in 2002. At that point, Peterson had never heard of U2 or Bono. But the rock star and the poet have since formed an unlikely friendship. This was documented in a short film released last year by Fuller Studio. The 20-minute video sees the two friends in conversation about their shared love of the Psalms. For Peterson, it was the first book of scripture he fell in love with. For Bono, it’s the book that has inspired so many U2 songs (most notably ‘40’, which is based on Psalm 40).

During our wide-ranging interview, 85-year-old Peterson chooses his words carefully. He speaks slowly, thoughtfully and briefly – never mincing his words. Not only does he tell me that megachurches aren’t real churches, but when I ask, “Do you have any tips for marriage?” he lambasts me: “Tips is the offensive word in the question! Marriage is not about ‘tips’ but a way of life that gathers everything of both yourself and your spouse into something integrated and honoured.” He’s right, of course.

Peterson has spent his life leading a small church, writing over 30 books and teaching theological students. Now in his latter years, he’s become a pastor to pastors, often gathering them to his stunning lakeside property in rural Montana for times of fellowship. It’s there that he passes on his wealth of wisdom and life experience.

At what point in life did you feel called to be a pastor?

I grew up in a Christian home and church but never knew a pastor that I trusted. I thought that I would never be a pastor. I was in my 20s, newly married in New York City when I said to my wife one day, “I think I am a pastor – I think I have always been a pastor.” It was the tawdry culture in which I was living that I was motivated to do something about it – and in a couple of years I had become a pastor.

You’re also known as a contemplative. Where did that come from?

When I was 12, my parents had moved us across town where I had no friends. I bought with my own money a Scofield Bible and started reading it. I didn’t understand it.

Someone told me to read the Psalms, which I did, but that was worse! I didn’t know what a metaphor was and insisted on being literal with every word. I stubbornly kept at it under the conviction that if I just read long enough and stubbornly enough, I would get it. And then I got it – poetry. The psalmists were poets and I began to absorb beauty, the sounds and repetitions, and became a contemplative – realising that language was not just telling me something but inviting me into a world of language that was more about what you couldn’t see than what you could.

How would you encourage Christians to engage more with the Psalms?

There are many ways to encourage an attraction. My own way was to memorise a psalm. All the Psalms are prayers of one kind or another. If you are in a hurry, you’ll never make it. I usually ask people who are interested to print out a prayer or poem and carry it through the day and memorise portions of it whenever there’s a chance of privacy. Patience is required. And also curiosity for poetry in contrast to prose insists on assimilating sounds and meanings that take some time to take in.

What was it like filming the documentary on the Psalms with Bono?

It was very refreshing. I think Bono is the most unpretentious person I’ve ever met. I’ve been with him several times and I feel friendly with him. He’s not critical of anybody. He’s very gracious.

He knows the Psalms as well as I do. I was totally relaxed in his presence. He was not trying to teach me anything and I was not trying to teach him anything. We just fit. We both love the Bible and love the Psalms. He has his own way of translating that to the people he’s writing music for.

You’re best known for translating the Bible. Do you view The Message as your legacy?

Not really. My writing is shaped to convince pastors to be real pastors – to embrace a congregation as a spiritual father or mother. The Message had its origin in my preaching, developing a pastoral imagination and not just a spiritual task here and there. It was something comprehensive.

Could you outline some of the reasons why you chose to translate The Message in the way you did? You’ve talked before about there being a distinction between translating “What did she say” and “What did she mean”.

The difference has to do with listening. And listening requires patience, sometimes much patience. It requires curiosity, wanting to get at the heart of what is said. We can’t be in a hurry if we are really interested in what is being said.

I was trying to translate The Message into the vernacular I heard around me in English. I know English really well and I know Hebrew and Greek narratives well. So I was just trying to translate into the language my parishioners used. To tell you the truth, I’m just absolutely surprised at the reception that it’s had. People are saying, “I never understood the Bible until I read this.” That’s the most common response that I get.

Psalm 23 The Message translation

God, my shepherd! I don’t need a thing. You have bedded me down in lush meadows, you find me quiet pools to drink from. True to your word, you let me catch my breath and send me in the right direction. Even when the way goes through Death Valley, I’m not afraid when you walk at my side. Your trusty shepherd’s crook makes me feel secure. You serve me a six course dinner right in front of my enemies. You revive my drooping head; my cup brims with blessing. Your beauty and love chase after me every day of my life. I’m back home in the house of God for the rest of my life.

Have you encountered any criticisms of The Message?

A few years ago I would get nasty letters about how I was twisting the Bible to my own agenda. I wrote a thing for my publisher to send to them. I said every language is different. You can’t translate the Bible literally from one language to another. If you’re willing to learn Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic, then we can talk about this. But if you’re not willing to learn the language as it’s given in the scriptures, we’re just talking blind. I’ve never got an answer from people like that!

Are there common pitfalls that Christians are susceptible to when it comes to how they read scripture?

Having an agenda. If we have an idea of what God is saying we’re not paying attention to it, we’re imposing our own agenda on it.

So much of evangelical culture is built around loud, large-scale events. Quiet memorisation of scripture, which you mentioned earlier, isn’t always encouraged. You’ve been critical of the megachurch model in the past. Why is that?

A megachurch is no church at all. It’s all mega and no church. It is entertainment, pure and simple. No matter how good the preacher is, it is not preaching – there is no participation. Everything that the church has as its core values – names and relationships, quietness and listening and prayer is essentially eliminated.

What do you find encouraging about the state of the Church today?

Much. Very much. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t get a letter from at least one and often several letters of someone saved from ambition and success.

We live in a media-saturated society. But I understand you’ve resisted this by limiting your use of the internet and not having a TV. Would you encourage other Christians to take these steps?

Yes, I do resist a media-saturated society. If you have children, gather them after a meal and read them Tolkien or Lewis or Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Take them on walks through the woods, get them interested in identifying birds. Every family is different. Use your imagination.

We never had a television until my wife got pregnant, and then as the children grew, it was controlled.

What does life look like for you now?

I’m not retired. But I am 85 years old. I think I’ve completed my last book, it was just published – As Kingfishers Catch Fire. The title comes from ‘Dragonflies Draw Flame’ – a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins. One of the things that pastors deal with is you’ve got to read the whole Bible to understand any one part of the Bible. When people start interposing their own judgements of other places in the Bible onto the text without the context of the text – that’s when they fall into difficulty. I’ve read the Bible all my life in its original languages and I think I do understand the whole Bible and interpret parts of it in the light of everything else.

So if you’re not writing anymore, how are you spending your time?

I listen to people a lot. I do a lot more listening. I’ve always felt my task as a pastor was to listen to these people as carefully as I could and understand what they’re saying. Then if necessary help them understand what the Bible says and what the Spirit says. It’s not that difficult, actually.

As Kingfishers Catch Fire (Hodder & Stoughton) is out now