Twelve months ago, the Church entered the month of March in much the same state as it had been for years. The usual internal battles continued to unfold – Franklin Graham insisted his evangelistic tour would not be derailed by LGBT protests and a Catholic cardinal was forced to resign over an alleged abuse cover-up. The theological concerns were not new either – Premier Christianity’s March 2020 issue saw Louie Giglio reflecting on student mission while Glen Scrivener explored the ethics of abortion and Down’s syndrome. There was no indication that the Church, far from plodding along as normal, was about to enter the most seismic year it had seen for perhaps a century.

The coronavirus pandemic has upended everything. Church services mostly take place on the internet, but sometimes to congregations twice their regular size. International travel, conferences and festivals have all been cancelled. Urgent theological debate now centres on whether communion can take place virtually and if Christians should resist government-imposed restrictions on our services. One year into the Covid crisis, how exactly has it changed the Church? And, just as importantly, with the end of the pandemic beginning to creep into sight, how many of these sweeping transformations will last?

The digital explosion

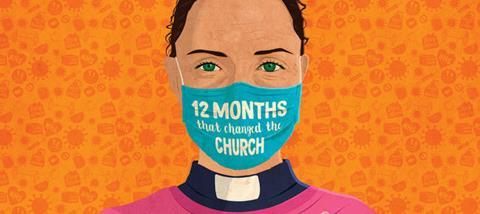

By far the most obvious shift in the Covid era has been churches of every shape, tribe and size moving their services online. Whether livestreaming on Facebook, uploading prerecorded videos to YouTube or hosting Zoom meetings, almost every church in the land will have broadcast in some manner via the internet. While it has been legal to resume some in-person worship since last summer, many churches are yet to return physically and almost all continue to offer services online even if they now also meet in the flesh.

It is this hybrid model that many leaders are convinced will become the new normal, even once all the restrictions are finally lifted. For while the move online was imposed at short notice by the first lockdown, it has born unexpected fruit. Many say the lockdown has opened their eyes to just how many people in their parishes, communities and congregations had been excluded from church before.

“It feels like the vast majority of churches have never really considered the people who simply cannot get to the building,” reflects Kate Wharton, a vicar in Liverpool and assistant national leader with New Wine. The disabled, unwell and housebound can now engage fully in the life of the church like never before, but so too can those with unusual shift patterns, or those who, because of mental health problems, find large groups of people difficult.

Rt Rev Dr Graham Tomlin, Bishop of Kensington, believes the story of Covid so far is about all kinds of widened access to Church. He comments that if he had launched a campaign to get all his clergy livestreaming services before the pandemic it would not have got very far at all. “What would have taken us ten years in normal times – catching up with the digital revolution – has happened in a year.”

Arun Arora, a vicar in Durham and the former head of communications for the Church of England, recalls how back in 2016 his team had run a pilot programme of broadcasting church services on Twitter for a year, only to shutter the scheme as there was so little take-up. But having been thrown in the deep end last March, many church leaders have discovered there is now a huge demand for weekly online worship.

In one survey by researchers from Manchester Metropolitan University, as many as 90 per cent of clergy said they would continue to use techniques picked up over the last year. Not least, because offering church online – especially for those utilising the livestream model – has seen hundreds of thousands of people take part for perhaps the very first time.

Almost every church leader you speak to has stories to tell of newcomers who, despite never darkening the doors of a church building prior to coronavirus, are now logging in – sometimes from hundreds or even thousands of miles away. “It takes quite a lot of courage to walk through the door of a church but you can very easily just watch somebody’s video service without anybody knowing from your pyjamas with your cup of coffee,” observes Right Rev Dr Emma Ineson, Bishop of Penrith.

Pete Phillips, a Methodist minister and theologian specialising in digital issues at Durham University, says his research has shown a phenomenal increase in people trying out church online since the pandemic began. In a professional survey last September, 28 per cent of those polled said they had engaged with some kind of online worship. “The potential increase in regular worship is four million in a week to 15.6 million,” he says. “That’s just unbelievable.” Some have been intrigued enough to attend online Alpha courses, join the church family formally, or even get baptised. When looking forward, many church leaders excited by these possibilities sketch out a future where non-Christians are first encouraged to try out church from home online, before gently being encouraged to come in person.

This hybrid model may also include keeping midweek meetings and home groups online permanently. The pioneer of the Alpha course, Nicky Gumbel, has admitted he was initially very reluctant to hold the courses online. In an email to Alpha leaders earlier this year, he wrote: “This is another occasion where I have been proved wrong. I didn’t think Alpha would work online, and I never thought I would be saying this, but I now think Alpha online works even better than Alpha in person.”

Phillips agrees it has proven much easier to invite non-believers to evangelistic courses that are held online rather than in person. And others note how evening events on weekdays are much more accessible when done on Zoom – particularly for parents who cannot leave the house because of childcare needs.

But not everyone is excited by the sudden quantum leap in digital church. Several leaders have expressed concerns that current church members will be tempted to stay tucked up in bed on Sunday mornings and watch church online rather than make the effort to commit to physical community and fellowship. Others are worried larger churches with higher production values will suck away congregants from smaller and less tech-proficient parishes.

Other leaders have deeper concerns, especially around communion. “We are unintentionally gnosticising the Church,” warns Andrew Wilson, a teaching pastor at King’s Church, London. “The medium is the message; you intentionally communicate that this is a thing you can do at a distance without sharing a cup or a loaf with anyone.” Online church is like a marriage conducted on Skype between two people in separate continents, he argues: it might be able to limp on for a while but real church, much like true marriage, can only happen when people come back together in person.

Phillips’ concern is different. He worries that broadcasting church services to anyone who wants to watch will turn denominations into a religious version of the BBC and could represent a form of “selling out [and] merging with contemporary culture”. Instead, he believes churches must focus on how to use digital tools to ‘narrowcast’, blending physical and online communities together and remaining laser-focused on how to connect interactively with people, not simply churn out ‘content’ to the anonymous masses.

Yet, despite significant technical and theological hurdles to overcome, most leaders seem confident the hybrid digital-physical future of church will turn out OK in the end. As the pandemic enters its second year, Christians seem to be as desperate as anyone to rekindle in-person relationships. Theologian and writer Krish Kandiah says any initial worries about a permanent end to physical church has been wiped out as the coronavirus crisis grinds on and on: “We miss it like crazy. As soon as it’s possible, people will be itching to be together again,” he predicts.

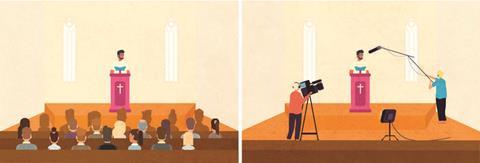

The fragility of youth ministry

If the digital transformation story is one of innovation and excitement, the second major change felt by Christians over the past year is mostly the opposite. While it has turned out more possible than almost anyone thought to persuade adults – both believers and seekers – to do digital church, it has proven extraordinarily difficult with children and teenagers. “One thing that’s happened throughout lockdown is that we as a church realised, devastatingly, how fragile a lot of youth ministry and relationships with children and young people have been,” comments Rachel Gardner, director of national work at the charity Youthscape. “If you’re in a church where you have kept in touch with your young people, that’s absolutely brilliant, but that’s not the national picture.”

According to figures gathered by the Evangelical Alliance, about 35 per cent of churches surveyed last year were doing no kids’ work, either in person or online. Youthscape research suggests on average churches have lost contact with about two-thirds of the young people they were working with before the pandemic struck. Teenagers in particular are understandably not enthused about joining tepid Zoom calls instead of their usual Friday night youth group with pizza and PlayStation.

“It is massively worrying,” says Wharton. “Teenage years are already the time we lost most people.” If an entire cohort of children fall out of youth work and thus never become Christians at all, the Church could have a permanent lost generation, long after the pandemic ends. David Voas, a leading sociologist of religion from University College London, says the pandemic could be a “critical moment” for this very reason. Most religious decline in the West had largely been the result of young people not following in the faith of their parents and grandparents, so a large drop-off in adolescents engaging with church would only exacerbate plummeting church attendance figures.

To avoid the British Church coming out of Covid as an even older and staler institution than it already was, Gardner says there has to be a “whole-church, big-hearted, audacious vision” to reorientate mission around emerging generations. “This doesn’t mean other age groups don’t matter, but this is the moment for the Church to say: ‘We want to be a church which is growing into the future’. I think it is as stark as that.” And for a cohort of young people emotionally scarred and anxious after a year or more without much human contact, perhaps that needs to be a simplified, more authentic kind of youth work, which abandons efforts to be cool and instead focuses on relationship. After all, once life returns to normal there will be countless other places where teens can be entertained far better than church could do, Gardner concludes. “But what we do far better than anybody else is walk young people in the path of life.”

The social action surge

The final significant shift prompted by coronavirus is the surge in community engagement and social action. Rather poetically, as church buildings emptied on Sundays under lockdown, the streets around them began to fill up with Christians Monday to Saturday. Church leaders have been encouraged and inspired by how wholeheartedly their congregations have risen to the challenge: starting foodbanks, delivering prescriptions and groceries, staying in touch with the isolated and lonely, volunteering to help deliver vaccinations.

By being ordered to stay at home, many Christians – like the rest of society – have found themselves reorientated to their local community. The HTB-organised network Love Your Neighbour has seen thousands of Christians from dozens of churches form hubs in their cities and towns, partnering with foodbanks, charities, schools, hospitals and businesses to send willing Christian volunteers to wherever the need is greatest. Bishop Emma says one of her vicars has even taken up a job in the local fish and chip shop – one of the few things still open in lockdown – in an effort to reach her community in the absence of Sunday services.

For Bishop Graham, the flourishing of social action is part and parcel of the widening of access to Church through digital means. “I can think of a couple of our churches whose foodbanks have tripled in size this last year, compared to the year before,” he says. “And they’ve become real community hubs for their neighbourhoods, linking in with social services, becoming a prime frontline provision of support.”

Gardner, who is also one of the leaders at a church plant in Preston, says it was unlikely her congregation would have thrown itself into social action if their lively, charismatic worship services had not been forcibly shut down by the pandemic. “I think on the whole we would have waited for people to come to us,” she reflects. But by getting “boots on the ground”, it has transformed her still nascent congregation. “We saw people grow because they were doing stuff. It changed how we pray on a Sunday, it changed how we worship, how we preach. If we know that they’re afraid of losing jobs and health and fearful of domestic violence then that suddenly transforms how you preach on a Sunday morning. So yes, that’s been extraordinary.”

These efforts not only show God’s love in the here and now, but could bear fruit long into the future too. Kandiah recounts a story of how decades ago he had been part of a Salvation Army band playing music on a beach. A stranger came to talk with them and ultimately hear the gospel explained, simply because he remembered how, 50 years earlier, the Salvation Army had helped him practically during the Second World War. “If the Church continues to pour love and mercy and care into the most vulnerable people, that will linger long in the memory, even longer than the memory of the pandemic itself,” he says.

And many hope that this will not be short-term emergency action during a national crisis, but instead a permanent shift in emphasis for the Church. Lockdown has made everyone re-examine their priorities, Arora notes – whether that is how much time they spent at work or what they truly want to get out of life. “Friendship is being rediscovered, voluntary kindness and service being celebrated,” he says. The same must happen in the Church too, he and others conclude. “If nothing else, everybody’s got to know the names of the people who live to the right and the left, if they didn’t know them before,” laughs Wharton. “And maybe even that’s a bit of a step in the right direction.”

Revival or survival?

At the start of the first lockdown, many Christians became excited that God might be kicking off a revival. There were anecdotal reports of churches seeing hundreds of newcomers log in online, sales of Bibles surged and even Google searches for “God” and “prayer” went through the roof. After ‘The UK Blessing’ worship video went viral, Pete Greig seemed cautiously optimistic. “Is something stirring?” he wrote. “Prayers that some of us have been praying for decades, suddenly seem to be finding answers in the most unexpected ways.” Others feared the opposite: a collapse of Christianity in Britain, as believers locked out of their church buildings and struggling to see where God was in the crisis lost their faith for good.

One year on, it remains unclear if either of these scenarios has unfolded. Some surveys do show staggeringly high numbers of people claiming to engage in online worship. But YouGov research in November concluded the pandemic had had a negligible net impact on faith: five per cent of those polled said they had found faith or seen it strengthened during the crisis, almost entirely offset by four per cent saying they had lost their faith during Covid-19. Peter Lynas, the national director of the Evangelical Alliance, says their research tallies with this: definite increases in numbers but also clear signs of less engaged and more nominal Christians drifting away. The death of nominalism has been a trend in the UK Church for years. Perhaps this is the death knell? As Lynas comments: “This kind of cultural Christianity; I do wonder how that that will survive or come through this.”

As we enter the second year of Covid, the picture remains decidedly murky. “Is this the beginning of a great growth of the Church or is it actually a winnowing of the Church? We don’t know at this stage,” remarks Bishop Graham. What is needed now is “perspective and prophets”, to discern what God has been saying through coronavirus. Arora, who says one of the greatest changes in his congregation has been a renewed commitment to prayer, agrees and urges churches to take time to discern even in the midst of financial headaches and technical challenges. Quoting Jesus’ words to Nicodemus, he says believers must remember that the Spirit of God is like the wind – not controllable or even predictable, but always on the move. “What is the new normal? It’s about discerning where God is on the move throughout this and recognising there is no going back.”