Rev Jill Richardson shares a heartwarming tale of her decades long friendship with Wally

A blonde woman signalled through the window, gesturing me to come closer. She opened the door a crack.

“Are you Jill?”

“Yes,” I replied.

She opened the door further. “Hurry, get inside – if all those people find out who you are, you’ll be mobbed.”

“All those people” were the 25 or so guests waiting for the soup kitchen to open at the St Vincent de Paul centre in Watertown, Connecticut. I raised my eyebrows and gave her a curious glance. Why would I be mobbed by a crowd of homeless people, like they were the paparazzi and I a celebrity at an award ceremony?

“Walter spoke of you all the time. You’ve become a kind of legend around here.”

Becoming pen pals

I didn’t start out to be a legend. As a young newlywed teacher, I simply felt drawn towards prison ministry, so when the opportunity to sign up for a pen pal programme with a prisoner came up, I thought: Why not? I was matched with Wally, a 26-year-old man who had been in trouble most of his life. Wally’s drug habit led to a string of burglary and other charges that kept him spinning through the revolving door called the American prison system.

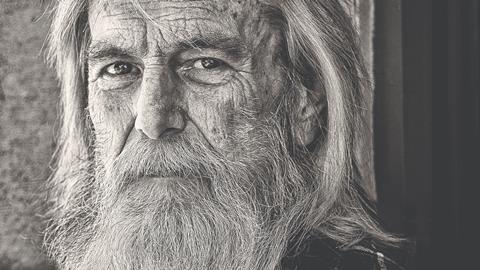

He sent me a Polaroid shortly after we began writing – a tall, big-framed man with lanky blond hair and a wizardly beard. “I promise to get a haircut”, he wrote, trying to live up to a standard he imagined I’d call “good”.

“Your hair looks great”, I wrote back. In the years to come we would talk more about what “good” meant and its location in the heart, not the hair.

Wally also sent artwork. He took up oil painting in prison and his work hangs all over our house. People often ask about the large painting over our piano – two little girls by a bright pink house, flanked by a river bathed in sunset. They never suspect its origin.

Neither of us knew what we were stepping into when we put the first stamp on that envelope

That one short application to write to a prisoner started a correspondence that spanned 35 years, four states and at least ten different prisons. When we began, I addressed my letters to Ossining, New York. I had no idea they were going to the infamous Sing Sing Correctional Facility. Maybe you’ve heard the phrase: “Send him up the river”? It was coined for Sing Sing, a dangerous, maximum-security institution 30 miles up the Hudson River from New York City. It’s synonymous with the worst kind of prison experience, and though Wally rarely told me what really went on there, he survived two decades of its horrors.

We learned to imitate the mechanical voice that announced each week: “You have a collect call from…Wally.” As we talked, I could hear the annoying ‘bing’ behind him that registered each minute of our timed and monitored conversations.

In those short telephone calls, Wally and I talked about forgiveness, the weather, salvation, animals, the all-encompassing love of God and fishing in his beloved Connecticut River. We shared a passion for Maine Coon cats and rolling rivers that met the ocean. When he talked about his dream of setting up camp by the river, I pictured it like the ones near my home – gentle, narrow and worth wading into on a hot July day.

All of our deeper conversations about theology and faith had practical meaning for Wally. His family had committed neglect and sexual abuse, which he struggled to forgive and heal from. He had given his life to Christ in prison before we met, but the contents of that life made him doubt God could or would love him.

I went to Bible college and got ordained while our friendship grew, and I’ve never had a parishioner who used all my roles of pastor, counsellor, comforter and priest like Wally. Neither of us knew what we were stepping into when we put that first stamp on an envelope addressed to Montana or New York. We grew up together, from our 20s to our 60s; through most of life’s stages we somehow hung onto the unlikely friendship. He closed every conversation and letter with the same words. “You’re in my love and prayers.” Later, as our family grew, he would add: “Say ‘hi’ to the girls for me.”

Wally was the far more reliable correspondent, and I grew to recognise the unique cadence of his writing. If I had not heard from him for a few weeks, I knew something was wrong.

In the last years, when he was out of prison at least as much as he was in, the letters faltered and we relied more on phone calls and texts. Things like stamps, paper and pens are hard to hold onto when you’re living under a bridge.

A hard life

It would take more wisdom than Solomon possessed to balance the contradictions that were Wally. When did I question his truthfulness and when did I trust? When did I offer assistance and when did I help him do things for himself? When did I push advice and when did I accept the dignity of free will? He had never navigated the adult world outside the prison; it was like befriending Rip Van Winkle after he’d awoken from two decades of sleep to a very changed world.

We met in person only twice. Once, briefly, when I visited Boston to teach some classes, and once when Wally came to live with one of our church members, looking for a fresh start. I picked him up from the train station and didn’t recognise the man standing before me with his tattered backpack. Far thinner and older than the photo he had sent years ago, Wally looked every year of his hard life.

Investments of love grow in startling ways

We helped him arrange doctors’ and social service appointments. We shopped for new clothes and a haircut. Wally pitched in generously at church, helping stack chairs, serve coffee and whatever else needed doing. He loved it there, and people loved him.

Eventually, I grew confused by his lack of momentum – he had little sense of urgency about sorting out the identification documents he needed to access healthcare and employment. That’s when he told us he had to move back to Connecticut. His parole officer was threatening to put him back in prison unless he remained in state. As he boarded his first airplane, he insisted: “This will always be home – here with you all.”

I don’t think it was the parole officer that worried Wally away. I know now that Wally found it hard to fit in with Middle American suburban life. He didn’t know the ‘language’ or understand the expectations. He didn’t like being dependent on us to get to places. However difficult street life was, it was familiar; he knew how it worked. It wasn’t easy, but it was home, even if his heart yearned for friends halfway across the country.

A terminal diagnosis

Wally started mentioning more doctors’ visits in 2021. He texted about visiting specialists. He began talking to my husband, who was a doctor, more than to me, discussing his symptoms and treatment in detail. I knew he’d gone for lung scans, and I knew what he wasn’t telling me. As always, Wally didn’t want to worry “the only friend who has cared for me through everything”.

“I’m fine,” he’d assure me. “This is what happens when you get old and haven’t lived right.” He’d laugh, trying to throw me off. I wasn’t thrown off, but there was the dilemma again. Allow him the dignity of privacy and independence, or demand he be honest? Dignity always won.

I knew he was dying. I just didn’t know how fast, and he was determined that I wouldn’t. When the hospital called me, the nurse hesitated. “You’re listed as Walter’s next of kin. He says you’re his sister?”

I didn’t know what to say. I couldn’t lie, but I also couldn’t deny Wally the chance to have me there for him. “Um, not…exactly,” I mumbled.

“Well, it doesn’t matter. If Walter says you are, then you are. Everyone deserves the dignity of having their person with them when they’re dying.” I’ll never forget the kindness of that nurse.

I got on a plane.

While I was in the air between Chicago and Hartford, Wally passed into eternity. He would never be neglected or conflicted again. Wally was free and with Jesus. I, on the other hand, was sobbing in the airport, wishing I had arrived just a few hours earlier. I got to the hospital, touched his hand and whispered a prayer. Then I said goodbye to one of my oldest friends.

Wally taught me to see God’s face in drug addicts and homeless people

But our friendship wasn’t quite over.

The nurse handed me a Post-it note with a phone number. “This woman from a soup kitchen asked if you’d call.” I agreed to meet her and thus the strange scene unfolded, with her practically yanking me through the door and locking it against the early lunch crowd.

I sat at a table with two other people, crying and laughing as we remembered Wally, or Walter, as he was known to them.

“He was so loved by the other clients here. He always had a positive thing to say,” the manager said. “Walter made people feel good just by being around them.”

“He was my best friend,” the man across from me added. “He made me want to keep living.”

“He talked about you all the time. He told everyone about his friend from Chicago. They all want to meet you. You’re a celebrity here – you’re the person Walter said taught him how to care about all of them.”

Meeting Jesus

As a pastor, I’ve officiated at many memorial services, but I’ve never led one in a soup kitchen. But I can recommend it. The volunteers and staff put together a programme. I sent them photos of Wally’s paintings, which they copied and set in frames on the tables. Word got out. People came and told stories about Wally, quite colourful ones. I gave a short meditation and blessing, telling them what Wally, and they, had taught me.

From my friendship with Wally, I learned to see God’s face in drug addicts and homeless people. I discovered how to love people where they are and recognise how much of our lives are just about doing the best we can with what we have. That week, though, I learned the greatest lesson of all our 35 years together.

Wally lived a life that most people would call pointless. He was homeless, destitute, a criminal; a ‘non-contributor’ to society. Yet when I stood in that soup kitchen, I was surrounded by people whose lives he had touched in a profound way. They wept openly as they talked about him. Wally had loved and been loved by other humans who needed it. In that, he had lived a life that was far from pointless.

I may have begun writing to one prisoner, but that consistent love helped him learn to love others who didn’t have that consistency. Investments of love grow in startling ways; I had no idea how much my investment would return until I sat with 30 strangers in a soup kitchen, 900 miles from home.

As I stood looking at the river near the soup kitchen mission, I told them he would probably like his ashes scattered over it. They said they would make arrangements.

I was a celebrity in a soup kitchen for one day. For more than three decades, I was a friend to a man who had few steady friends. He got to greet Jesus before me. I imagine Jesus shaking his head at Wally, a wry grin on his face, then giving an enormous bear hug to a man who was never sure he could be loved. I imagine Wally saying to Jesus: “Send them my love and prayers.”

No comments yet