Thousands of rough sleepers were housed during the first lockdown, thanks to the government’s ‘Everyone In’ scheme. But now experts are warning that homelessness is back to pre-pandemic levels. Emma Fowle speaks to the Christian charities on a mission to house everyone

Ever since the earliest days of William Booth and the Salvation Army, care of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the UK has often fallen to the Church. From grassroots projects, such as soup kitchens and night shelters, to the formation of some of the UK’s largest homelessness charities, Christians have been at the forefront of both political campaigning and practical relief. In fact, most of the UK’s main homelessness charities have Christian roots, however obscured from sight they may now be.

Over the past decade, debt centres, food banks and night shelters have exploded exponentially and the Christian organisations who run them, such as The Trussell Trust and Christians Against Poverty (CAP) have grown in visibility. According to a recent report from the all-party parliamentary group on faith and society, the relationship between faith based groups – the majority of them Christian – and local authorities has never been better.

UNPRECEDENTED

The story of Christian organisations working hard to tackle the seemingly intractable problem of homelessness has been ongoing for years. But last March, as the first wave of Covid-19 hit the UK and lockdown measures were introduced, something unprecedented happened.

“For the first time in living memory, all church-run night shelters were closed,” says Jacob Quagliozzi, director of Christian charity Housing Justice. In reality, that meant that nearly all night shelters were closed, as Christian organisations account for 98 per cent of this provision, Quagliozzi tells me.

According to the official figures, 4,266 people were sleeping rough when the pandemic began (although Housing Justice reckon the true number may be double that). The closure of night shelters should have been a disaster for them, but instead a window of opportunity emerged. Declaring rough sleeping a public health emergency, the government vowed to “take everyone in”. Extra funding was given to local authorities to repurpose empty hotels, bed and breakfasts and even student digs to provide emergency accommodation for anyone who needed it.

And it seemed to work. By November 2020, rough sleeping in England had dropped by 40 per cent. “‘The ‘Everyone In’ scheme housed 37,000 people during the pandemic”, said the Salvation Army in a recent press release, “and gave a tantalising glimpse of what could be achieved when we work together.” But one year on, the “gains are already being lost”, they warn. Figures released in September showed an increase of 39 per cent in rough sleeping numbers, a return to almost pre-pandemic levels.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

In Scotland, however, the director of homelessness prevention at Bethany Christian Trust, Paul Stevenson, believes that ‘Everyone In’ worked not just in the short term, but the long-term too. He says the scheme allowed them to “expand the old care shelter model of only being available at night” into 24/7 facilities that kept people off the streets and gave them access to further support services. Their Rapid Re-accommodation Welcome Centre in Edinburgh, funded by ‘Everyone In’, housed 860 people over the course of the pandemic. What’s more, the charity reports that more than 75 per cent moved on to more permanent accommodation. But without the time, attention and friendship offered by the 1,000 volunteers (many from local churches) working alongside professional services, it would have been a very different story.

Phil Conn, of Christian homelessness charity Oasis Community Housing, agrees. “Just putting people in accommodation only solves one problem,” he says. Many statutory services closed overnight, leaving many (highly vulnerable) people feeling isolated and alone. It was, he says, “a really big gap” that churches and Christian organisations stepped in to close. “We worked with local churches to provide hot meals, and that was a really good opportunity to get eyes on people,” he says. In Scotland, when supported housing units closed communal areas, Bethany transported residents to local churches for lunch. And their Connect to Community scheme, which meets ex-offenders at the prison gate and supports them with accessing housing (among other things) was the only service of its kind in Scotland to continue through lockdown. “It came down to the definition of what was ‘essential’,” says Stevenson.

KEEPING THE FAITH

The “agility and flexibility” shown by faith groups during the pandemic was highlighted in a report by the all-party parliamentary group on faith and society in November 2020. Keeping the Faith highlighted a “new appreciation” of faith groups by local councils, calling them “vital resources which are crucial for community wellbeing, and which cannot be found anywhere else”.

Jon Kuhrt, who was subsequently appointed as the government’s first faith-based rough sleeping adviser, says it’s a huge endorsement of what churches and Christian organisations can do – and an opportunity to reflect on how they can best serve moving forwards. “Local authorities are good at some things but they can’t do a lot of things that churches can do,” says Kuhrt. “They can commission services, but they can’t really commission community.”

And it is here, he says, that the Church has something unique to offer. In the first-ever study of its kind, Lost and Found (Lemos&Crane) interviewed 75 long-term homeless people about their attitudes to spirituality and religion. It found that, for many, “religious belief and spiritual practice can help them come to terms with a past characterised by profound loss…and create a meaningful future built on hope, fellowship and purpose.” Despite this, organisations hardly ever asked homeless people about faith or encouraged them to attend places of worship. But by working with those organisations, Christians can help bridge that gap.

“Even at the height of ‘Everyone In’, there were still 2,000 people on the streets,” says Kuhrt, and not because there was a shortage of beds. “That shows how this is beyond just a material problem. It’s to do with trust, building up a relationship where people are willing to take that step to come indoors.” At the church-run night shelter where he volunteers, 14 of the 15 men put into hotel accommodation at the start of Covid-19 are now housed. Removed from the acute stress and anxiety of rough sleeping and supported by a loving church community, they were assisted to access benefits and apply for housing, hopefully changing their lives for good.

“If housing isn’t the solution to homelessness, I’m pretty certain community is,” says Conn. Sustaining accommodation is often the real challenge, and the support of Christians to deal with underlying, long-term issues can really make a difference. Kuhrt would like to see the Church focus more on providing what money cannot buy or council services provide: time, friendship, support and understanding; a sense of identity and a hope for the future. “Churches bring people into places not just of transaction, but of community,” he says. “No one says ‘my life was changed when I walked into a church and people gave me a bag of free stuff’.” Instead, empowering individuals to take responsibility helps foster long-term change. It might seem ‘glamorous’ to do the soup run and post a picture on social media, he continues, but the harder path is investing in relationships for the long haul, looking out for new people, listening well and supporting those with debt, addiction or mental health problems. This tackles the complex problems that can otherwise lead to someone ending up on the streets.

HIDDEN FIGURES

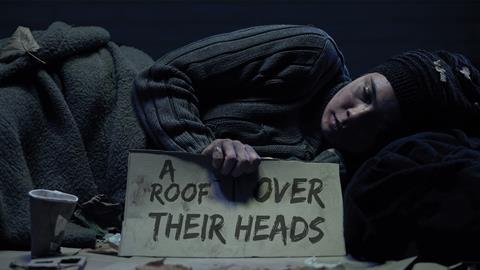

But homelessness is not just about rough sleeping. “The average person’s image of somebody who’s homeless is a white man with a beard in a beanie hat and a sleeping bag on the street,” says Quagliozzi. “But there’s probably about 10,000 people who sleep rough during the course of a year, and something like 100,000 people who will be in housing need at any one point. More than half of those people will be women. And you’re much more likely to be one of those people if you’re an ethnic minority and a woman.”

He goes on to explain that, often, it falls to churches to pick up those who fall through the gaps: the ‘hidden homeless’ sleeping on a friend’s sofa, victims of domestic violence or people with irregular immigration status and no recourse to public funds, such as housing benefit: “Without faith groups, the system would really struggle,” he says. “In some areas, there’s not enough capacity without a faith group. In other areas, faith groups are picking up people who would not be able to access the local authority-run services.”

As the world emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, Malcolm Page, assistant director of the Salvation Army’s homelessness services, describes the challenges facing the poorest and most vulnerable today as a “perfect storm”. Winter brings higher heating and lighting bills, and energy and food prices have risen rapidly. ‘Everyone In’ funding, the temporary uplift in Universal Credit and the government’s furlough scheme are all ending. Local Housing Benefit levels have been re-frozen, meaning that, as rents rise, the help some need to pay the bills does not. Many thousands more people may be at risk of losing their homes in the coming months.

Faced with huge need, Pete Cunningham, founder of Christian charity Green Pastures, gives a clarion call to the Church, encouraging us to remember the example of the good Samaritan in Luke 10 and not “abrogate our responsibility to care for the poor”. We have worked hard throughout the pandemic, but that does not mean we should “become weary in doing good” (Galatians 6:9).

Since their inception in 1997, Green Pastures has helped churches purchase property to house the homeless with one clear aim: “The reason we house the homeless is Jesus”, it says on their website, and Cunningham is passionate about the opportunities that providing stable homes – and the support that goes with it – creates for changing someone’s life.

“We have seen some amazing changes in people simply from giving them a key to their own home. Alcoholics are now free from their alcohol addiction, drug addicts are now free from their drug addiction, unemployed young people with life skills problems are now working, mothers who had been brutally beaten are now housed with their children, and so much more. But most wonderful of all is the number of people who have come to Christ, not through our preaching of the gospel, but by our doing the gospel.”

Local authorities are good at some things but they can’t do a lot of things that churches can do. They can’t really commission community

Cunningham quotes Galatians 2:10, when Paul visited the church elders at Jerusalem and was extended the hand of fellowship: “All they asked was that we should continue to remember the poor, the very thing I had been eager to do all along.”

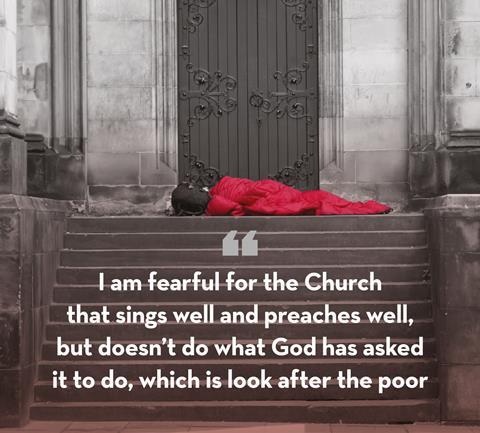

“Are you eager to look after the poor?” he asks me pointedly. “Because I am fearful for the Church that sings well and preaches well, but doesn’t do what God has asked it to do, which is look after the poor.” We might think that we are doing well, he continues, but we’re not. If every church in the UK invested just £100, he says, Green Pastures could create an additional 25,000 bed spaces, moving a long way towards ending homelessness for good.

As the interview draws to a close, he offers to pray: “Father, I want to thank you for this conversation we’ve had. Because our heart is to build your kingdom. You know, when you taught us to pray you said ‘thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven’ and you want your kingdom to be seen here. It’s not being seen at the moment, Father. Help us to bring it about for Jesus’ sake.” Feeling suitably inspired, and challenged, I rejoin with a hearty “Amen”.

Click here to read Chaz’s story of finding Jesus at a Christian housing project and leaving a life of drugs and crime behind to help others make a fresh start.

5 ways to show support

Many churches will encounter people experiencing homelessness, even if not directly involved in homelessness programmes.

These five basic principles from Housing Justice can help you offer the right support:

1. People before problems

It takes time to build trust. Be kind and friendly; if someone shares issues around their housing situation, listening is often the best initial course of action. You do not need to offer solutions. If you do take action, make sure they consent and take care not to raise expectations or overpromise.

2. Preparation

While you will not be able to prepare for every eventuality, you can ensure a basic level of preparation. Find the telephone numbers of your local council housing team (including out of hours), local homelessness service and StreetLink. Place them somewhere they can be easily accessed. Consider providing training (Housing Justice can help with this) and nominate one person as a lead for enquiries.

3. Partnership

No single organisation or person is ever responsible for resolving a person’s housing needs. It requires partnership working and the consent and willingness of the person concerned. Helping people engage with the agencies who have the resources and expertise to support their (often complex) needs is one of the most effective ways churches can help. Your local council is legally responsible for supporting people experiencing homelessness. Regularly speak to them to ensure you are aware of local issues and the level of need.

4. Protection

Apply the same safeguarding practices to working with people experiencing homeless as other areas of church life. Avoid situations that could put you, or them, at risk. Where possible, don’t work alone and meet in church or public spaces. Be clear about boundaries and acceptable behaviour. If you are concerned for someone’s safety or wellbeing, you don’t need their permission to contact your local safeguarding team or NHS mental health helpline. If you believe someone is in imminent danger, call 999.

5. Prayer

Prayer should underpin everything we do. Christians should be confident in offering prayer, but support or services should never be conditional on the person receiving it. The charter for Christian homelessness agencies, available from the Housing Justice website, sets out how this can be done well.

For more information and resources visit: housingjustice.org.uk