As the unique Christian festival celebrates its 50th birthday, Derek Walker looks back at the event’s most memorable moments

Groundbreaking, controversial, distinctive, inclusive, faith-based, life-giving. These are just some of the phrases that have been used to describe Greenbelt.

Over the five decades since the festival began, it has carved out a unique slot in the Christian summer festival landscape, one that is alternately seen as a welcome refuge and inspiration for some, but unsettingly provocative by others. But one thing that both fans and critics can agree on is that the event has evolved considerably, and is now barely recognisable from its humble beginnings.

The early years

From V Festival to Creation Fest, today’s festival-goer is spoilt for choice, with a litany of both Christian and secular options available. But when Greenbelt began in the 1970s, there were very few models to follow. Rt Rev Graham Cray, former Bishop of Maidstone, a festival speaker and former board member, remarks: “I’m glad that we didn’t know how much we didn’t know!”

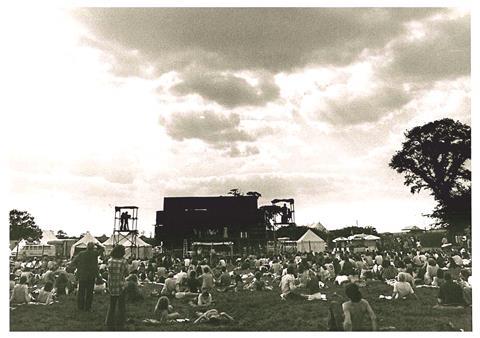

With police leave in Suffolk cancelled and reports of locals barricading themselves into their houses, the first Greenbelt Festival took place on Prospect Farm in Charsfield, Suffolk in August 1974. As it turned out, the police left just one of their force on site, as the crowd was so well behaved.

Greenbelt’s founding figurehead, James Holloway, was a bricklayer and theologian – which may explain his insistence on Greenbelt’s holistic ethos, rather than endorsing a sacred-secular divide. So while their businessman sponsor Kenneth Frampton wanted a mainstage altar call every night, Holloway – along with singer-songwriter Rev Garth Hewitt and fellow theologian John Peck – refused, insisting on a programme that celebrated its faith through the arts and social justice.

According to Cray: “There was a clear – if embryonic – vision from the beginning of an arts festival that was distinctive, if not unique, in the evangelical scene at the time; a sense of something that expanded Christian vision.”

It is easy to forget, in today’s era of Portaloos and field showers, how basic the facilities were. Wooden planks over deep trenches held plywood boxes with toilet seats mounted on them. Apparently one mischievous festivalgoer developed a specially shaped coathanger with a feather on the end that could reach an adjacent bottom. Shrieks ensued.

We are not seeking to reinforce what our audience already believe, but to bring their beliefs into encounter with the ideas and artistry of the wider world

By 1979, Greenbelt’s attendance had grown to some 20,000 people. Sir Cliff Richard headed a line-up that also featured Randy Stonehill, Bryn Haworth and After the Fire. After the morning Bible study (which covered topics similar to events like Spring Harvest - George Carey on ‘The Holy Spirit’; Graham Cray on ‘Gifts of the Spirit’) Greenbelt also showed its earthier, edgier side, with talks entitled ‘Politics in Thatcher’s Britain’, ‘Dealing with delinquency’ and ‘Living simply’, alongside pioneering discussions on racial justice and sexuality, which would still be the focus of attention decades later in the Christian world.

In 1979, the entire listing fitted comfortably onto two sides of A4. Just over ten years later, the 1990 festival programme was a glossy 84-page magazine. Its punchier, flashier and more culturally aware line-up was both seminal and celebratory, showing the confidence that Christians musicians felt in taking on a secular marketplace.

Poet and author Steve Turner’s piece in the physical programme, suggesting that Christians should address questions that the world is actually asking, captured the Greenbelt approach. He called it: “an ongoing attempt to locate the heart of the discussion in our world. That’s why it [the festival] brings in those questionable films and…those dubious liberal speakers in dog collars. It wants to make sense of our age with a Bible in one hand and a…play script, political manifesto or foreign news report in the other.”

Controversies

In that same programme, Graham Cray took the unusual step of addressing the absence of one particular church group from that year’s event. The Nine O’Clock Service (NOS) from St Thomas Crookes, Sheffield, featured culturally appropriate worship with video, candles and incense. Its values were spot-on and its mentors highly respected names. Members of NOS had previously participated in Greenbelt in various roles.

Some in the Anglican hierarchy saw NOS as the way forward but, in 1995, the group was disbanded after its leader, Chris Brain, was found to have been grooming young women in the congregation. Investigative reporters from the Daily Express found connections between NOS and Greenbelt, although Cray says the mainstream press “had no idea” what either was truly about. Nevertheless, Cray felt “hounded” by the press over the issue.

“I think that, rather like Glastonbury on a much smaller scale, the Greenbelt audience trusts the festival,” he adds. “Controversies like NOS – and in particular the ‘post evangelical’ period and the change of stance on sexuality – led to a loss of a part of the evangelical constituency [which is] where we began. The main consequence being the loss of some youth groups – although the festival was properly developing into a more all-age event.”

And there were other controversies. In 1991, Greenbelt invited a white witch to explain his beliefs in The Hothouse, a venue created to specifically explore more contentious issues. Concerned festivalgoers surrounded the marquee, singing ‘Majesty’ to ward off any spiritual threat. In the Q&A session afterwards, a woman stood to criticise Greenbelt for the satanic effigies around the site, referring to birds strung up in the Castle Ashby woods – unaware that they were actually game hung to mature after grouse shooting.

But breaking down the barriers between certain groups is part of what Greenbelt does, providing a listening ear to many who – despite the ubiquitous ‘Everyone Welcome’ signs regularly seen in our churches – don’t actually always feel welcome.

“For a gay teenager, 1970s Yorkshire was a barren place, as was practically the whole of 1970s Britain,” noted Willie Williams. He first attended Greenbelt as a teenager, volunteering on a work party, and later DJ’d and compèred mainstage, before going on to become U2’s show designer.

“I did manage to find a few like-minded people around whom my church life revolved, but it was not something I was public about outside that context. I found the whole Greenbelt community fascinating, especially how fearlessly the festival would engage with people who might be persona non grata in other Christian circles. Greenbelt has moved on from being willing to face ‘controversial’ subjects bravely, to become a place where all subjects are just viewed as a part of life.”

Before they were famous

Milton Jones was almost unrecognisable in his 1990 programme photo without the wild hair. Several years before he found fame, he spoke to Greenbelt about experimenting with playing characters in his comedy, and was still camping there after he was firmly established as one of England’s favourite comedians.

Greenbelt was granted the first Special Events Licence for its own radio station on-site in 1983. Simon Mayo – along with other BBC staff – DJ’ed there before he joined Radio 1 in 1986.

Daniel and Natasha Bedingfield had a family band called The DNA Algorithm that reportedly played Greenbelt’s fringe. The siblings later went on to successful mainstream careers, with Daniel topping the UK singles chart in 2002 with ‘Gotta get thru this’ and Natasha’s debut album Unwritten selling more than 2.3 million copies worldwide.

Neo-Soul sensation Corinne Bailey Rae was part of the Leeds-based Revive Collective who once led worship at the event.

Singer-songwriter Kate Rusby attended the festival as a teenager to see Deacon Blue. She recalls: “I had no idea what to expect as we’d been brought up going to much smaller folk festivals, but it was totally brilliant. I’d never watched a gig as big as that before. We sang and danced all the way through. I still have my Greenbelt 90 mug.” She didn’t perform there until she was established, but when she did, Deacon Blue bass player Ewen Vernal was in her band.

Highlights

The performance of one of the biggest bands in the world at the 1981 festival is a particular highlight in the history of Greenbelt. When festival organisers first approached U2 about a headline slot, the band declined, citing a date clash with their tour schedule. But after praying about it, U2 phoned back to ask: “If we just come down with our guitars can you find us a floor to sleep on?”

As not all of the band were Christians, they added: “But you’ll have to say quickly, as we have to persuade [bassist] Adam.” For Cray, the answer was a “no-brainer”: “I said ‘Yes!’ immediately. They were great.”

Poet-broadcaster and mainstage compère Stewart Henderson remembers hatching a cheeky plan with Williams. Henderson explains: “[Bono] was to be decked out in a high-vis steward’s jacket, complete with hat and shades – at eleven o’clock at night, mind – to conceal his obvious identity. Off we ventured on to the site and voilà, Greenbelt’s incognito car park attendant was put to work. Our bordering-on-the-officious functionary asked punters to move their cars, whether they wanted to or not. As an exercise in traffic management, I can faithfully report that no youth leaders were harmed by these confrontations, but we do apologise if your unknowing encounter with a diminutive Irishman all those years ago has caused you to ceaselessly ponder since what you’d actually done wrong.”

Legacy

When Greenbelt began, many churches simply didn’t understand the value of the arts. Greenbelt inspired and released many Christians to feel more confident in their gifting and calling, but often bore the brunt of the Church’s lack of understanding.

Henderson asserts: “Greenbelt made it possible for a baby boomer generation of artists to pursue their God-given inclinations to go into the cultural marketplace and, through trial and error, become lights in their field.”

Cray believes that it has had “a huge influence on the expansion of many Christians’ vision of their faith, life and discipleship. It has also created an environment in which it is safe to ask questions, and to meet people with different views, traditions and stories. It’s very different from when we started, but it is an appropriate development of the original vision.”

A consistent thread throughout this story is that Greenbelt has become a home to many who feel spiritually disenfranchised and misunderstood by the mainstream Church.

As Henderson notes: “Greenbelt has excelled in foreseeing cultural shifts; although it didn’t feel like it at the time, because of the flak we attracted from sections of the evangelical wing. Greenbelt, innovatively, allowed space for compassionate theology to be applied to what has become known latterly as ‘the LGBTQIA+ issue’.”

Henderson’s songwriting partner Martyn Joseph says: “It’s been my ‘church’ for a long time. I don’t attend church regularly these days, but that gathering in a field never fails to touch my nerve ends and whisper belief to me. It’s enough for me to walk on. My understanding, from talking to many others, is they feel the same way.”

As the 21st century creeps forwards, the pool of credible Christian musicians has shrunk drastically – largely due to the Christian music industry’s inability to market anything beyond cookie-cutter worship music and the draining influence that this has had on musical talent in our churches. As a result, the mainstage billings that once drew the crowds to Greenbelt have lost their Christian edge, replaced by more secular acts with an ethical stance. But even here, the brave selection of Russian feminist protest band Pussy Riot in 2018 has proved almost prophetic, following Putin’s land grab in Ukraine.

Ethos

Greenbelt’s strapline reads: ‘Artistry, Activism, Belief’. But critics have lamented the inclusion of secular ideas in the growing seminar and arts programme, and asked whether Christian belief is the least addressed of the three threads.

Creative director Paul Northup insists not. Referring to 2017’s standalone Muslim venue Amal (hope), and speakers like this year’s Andrew Copson, CEO of Humanists UK, he insists: “We are not seeking to reinforce what our audience already believe, but to bring their beliefs and practices into encounter with the ideas and artistry of the wider world in which we all live. We do this because we’re Christian. Our Christian worldview seeks to embrace and dialogue, rather than to divide and conquer.

“Belief isn’t the least addressed, but it is the most ‘assumed’. From a Christian understanding, we look outward. We don’t then necessarily shout about it all the time. We seek to engage, explore, create and imagine together how we can find and make common cause with others who perhaps do not share our faith commitments; thinking about how we, as people of faith, live with integrity in a pluralistic culture.”

GREENBELT HAS BECOME A HOME TO MANY WHO FEEL SPIRITUALLY DISENFRANCHISED

Rev Molly Boot, a trustee of Greenbelt, also sees “belief as a vibrant and essential strand binding together all that Greenbelt is and does,” expressing itself in hospitality to others in a “holy generosity” that enriches the faith of all.

Boot adds: “If people see Greenbelt as ‘non-Christian’, then I can only think they’ve never been in the field; never celebrated communion with thousands; never traipsed across a floating bridge by torchlight to the Shelter for Taizé prayers; never raised a pint in worship at Beer and Hymns; never prayed the offices with the Franciscans; never sipped a non-alcoholic beverage in Hope and Anchor with the Methodists and watched the Spirit stir up beautiful, brave, difficult conversations about our faith…you get the idea!

“It is also the only Christian festival I would ever confidently invite my glorious, totally atheist parents to, knowing that they would love it, that they’d be embraced with open arms, and that they might sense something of the divine there.”

No comments yet