It might look like an irreverent comedy, but this film asks some big questions – and paints a picture of Jesus that’s beautifully beguiling, says Martin Saunders

There’s a difference between causing trouble, and making trouble. When it comes to Christian-baiting movies, Monty Python’s infamous Life of Brian falls very squarely in the latter category. The Pythons wanted Mary Whitehouse and friends to choke on their non-alcoholic drinks; they positively thrived on the controversy. But not all mischievous movies set in first-century Judea are alike, as the latest entry in this strange little genre proves. One thing does seem to unite every attempt to create comedy within the context of the Gospel stories, however: some people are bound to get upset. The question is: should they?

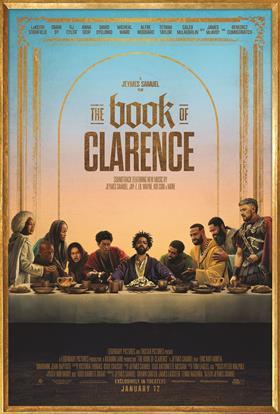

Jeymes Samuel’s The Book of Clarence, now showing in UK cinemas, appears at first to be a frivolity. Set alongside the latter events of the Christian Gospels, it’s more a light-hearted drama than a side-splitting comedy – although it does feature a few moments of striking and unsettling brutality. Samuel has attempted a fascinating piece of genre alchemy, placing a classic ‘hood’ story against a New Testament backdrop. And if that sounds like it shouldn’t work, think again.

A new messiah

The plot follows the three-step journey of Clarence, a small-time ‘herb’ dealer and opium-pipe enthusiast who just happens to be the twin brother of the disciple Thomas (both characters are played by the superb LaKeith Stanfield). Thomas gives the down-on-his-luck Clarence a glimpse into the hottest show in town: Jesus Christ and his band of disciples, all of whom are played by Black actors. But while Clarence is keen to become the “13th Apostle”, Thomas and the rest of the disciples are unconvinced by his claims to have found faith, as is John the Baptist (a brilliant cameo performance from Christian actor David Oyelowo). Spurned by the disciples, Clarence comes up with another, more outrageous plan.

In the second act, Clarence decides that he’ll proclaim himself “The New Messiah”, after seeing how much fame and apparent financial support Jesus has attracted. Gathering his own small band of disciples, he begins to perform fake miracles and give subtly humanist versions of Jesus-style sermons. His key message, that “knowledge is stronger than belief” begins to attract interest and support. His plan works and he quickly becomes wealthy from the donations his bogus ‘ministry’ hoovers up. But Clarence unexpectedly discovers that he has a conscience. He tries to assuage this by buying the freedom of a group of slaves, but he still feels unsatisfied. Then, the film – and Clarence’s life – take a grave twist: his messianic claims land him in trouble with the Romans and, through a slightly convoluted route, earns him the sentence of an agonising death by crucifixion.

In the third and final act, Clarence journeys towards and beyond his cross by way of encounters with Pontius Pilate and even God himself. At last, the humanist begins to look beyond himself; the atheist finds that knowledge and belief can be the same thing. Clarence is redeemed, and eventually – although the final scene includes some ambiguity – resurrected.

Politics and blasphemy

It’s easy to imagine how the film might cause offence. Aside from its depiction of Jesus himself – which we’ll get to – The Book of Clarence reuses important and sacred moments from the Gospel narratives to tell a fictional story. We see a character being whipped while he carries a cross through a baiting crowd; we watch a man being nailed and hoisted on to a cross in an image that is clearly meant to evoke the central moment of the Christian faith. At one point he walks on water; at others he subverts the cherished sermons of Christ. It could appear that this film is not only poking fun at the Christian story, but ridiculing it by placing a petty swindler in Jesus’ place.

But of course, Clarence is not meant to be the Messiah. He’s just, to quote Python: “a very naughty boy” and, among other things, this film is actually about what happens when broken people like him meet the real Son of God. The film never tries to claim that anything written in the Gospels isn’t true, or that a different messiah could ever take Jesus’ place. It’s really just a kind of midrash, imagining the kind of culture that might have existed around Jesus, and diving into the life of one of his many imitators.

It’s this attempt to explore an angle on first-century Jewish culture which gives the film its other major point of controversy. I should say at this stage that as a white commentator, I only have limited ability to comment on the significant racial dimension to the film. I’m no authority on the ‘hood’ movie genre, or on the many cultural and political issues that Samuel is referencing.

The filmmaker believes that Jesus is who he says he is, but perhaps he doesn’t look like we’ve imagined

That said, the film’s agenda in this regard is not subtle. The Hebrew characters in the film are all played by Black actors; the Romans universally by white men. Amid the comedy, there are several fairly lengthy, serious encounters between the group which dive deep into the issue of racial discrimination and oppression. The whole thing seems to be a metaphor for modern-day police brutality, with sneering soldiers jacked-up on power and authority, and references to the kind of racial profiling which plagues the lives of innocent Black people.

Again, it might be argued that Samuel is hijacking the most important story ever told, in order to make his own political point. But of course, when we consider the casting of his most famous character, it’s hard to imagine how a conversation around race could have been avoided. As far as I’m aware, The Book of Clarence is the first film to cast a Black actor in the role of Jesus Christ. British actor Nicholas Pinnock plays him almost completely straight, treating the part with the utmost respect and delivering a performance with no shortage of gravitas.

This portrayal of Jesus made me love the real Jesus even more

Here’s the really interesting thing: for me, every time Pinnock’s Jesus appears on screen, he is instantly compelling and the movie transcends to a different level. One scene, a meticulous recreation of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting The Last Supper is, in itself, a work of art.

Black Jesus, white Jesus

The biggest compliment I can pay to Pinnock and his director is that this portrayal of Jesus made me love the real Jesus even more. We see him briefly early on, his face shrouded and covered, but his first significant appearance – during a reimagined stoning of the woman caught in adultery – marks a major turning point in the film as it shows its supernatural hand. As Jesus freezes a number of thrown stones in mid-air, we realise that The Book of Clarence believes in Jesus. In this moment there is a palpable rush of excitement – Clarence’s downtrodden world contains an unmistakable source of hope, and we too are asked to consider if we’re willing to exchange knowledge for belief.

Every time we meet Jesus from this point onwards, including in the film’s final remarkable scene, there is a sense of thrill. Again, there are moments when Samuel seems to be skirting close to blasphemy, but it’s a line that I don’t believe he ever crosses. The impression you’re left with is that the filmmaker believes that Jesus is who he says he is…but that perhaps he doesn’t look like we’ve always imagined him.

That point is made beautifully by a late twist, a comic attempt to explain how we ended up with our classical depictions of ‘white Jesus’ in the first place. It’s the one part of the film that I’m loath to spoil, but suffice to say it includes a truly scurrilous cameo by Benedict Cumberbatch which, while played firmly for laughs, still manages to offer one of Clarence’s most thought-provoking moments.

A cultural rarity

If you can get past the apparent controversies of The Book of Clarence, thought-provoking is the operative phrase. It undoubtedly has something important to say about attitudes to race, including our cultural preoccupation with a blue-eyed, white-skinned Jesus. Yet there’s much more to it than that; despite appearing at first to be a slightly irreverent comedy, the film also has ambitions to get us thinking about the biggest questions of all.

For one: can a man find redemption, even when he’s stooped as low as imitating the Son of God? For another, is knowing really better than believing – and is it really possible to ‘know’ that your beliefs are true? But this film also manages – amid all the fun and politics – to pose the biggest question of all: who was this man Jesus who walked around Jerusalem in AD33?

The Book of Clarence is the first film to cast a Black actor in the role of Jesus Christ

Ultimately, Christians should welcome any movie or cultural event that manages to do that. Sixty years ago, biblical cinema was a Hollywood staple; today films that portray Jesus in such a favourable light are a rarity. The challenge The Book of Clarence has to overcome is that it appears to be something that it ultimately isn’t: an attempt to poke fun at Jesus and those who follow him. It’s actually quite reverent. The question is: will movie-goers see through the smokescreen of marijuana and apparent heresy, and realise that?

The Book of Clarence is now showing in UK cinemas

Jesus (don’t) be the centre

More movies that include Jesus as a minor character

There’s a small but significant micro-genre of movies set alongside the gospel story, which feature Jesus as a minor or even unseen character.

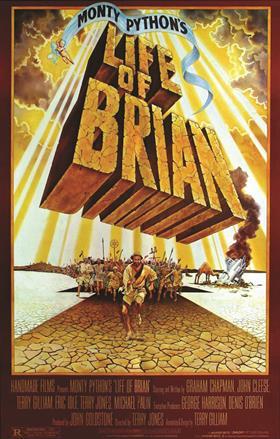

The Life of Brian

The original evangelical-baiter; Monty Python’s 1979 anti-epic about a man who keeps being mistaken for the Messiah still raises eyebrows in certain quarters. After Brian Cohen is born on the same evening as Jesus, he’s repeatedly confused with him, eventually meaning that Brian ends up being crucified. Jesus, meanwhile, is only portrayed briefly, and played with an unexpected degree of respect. John Cleese, who co-wrote the film, once said: “I don’t think it’s a heresy. It’s making fun of the way that people misunderstand the [Christian] teaching.”

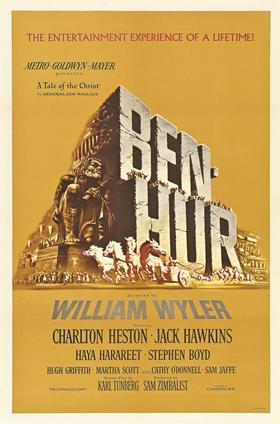

Ben-Hur

Perhaps the most famous story of all to be set alongside the Christ narrative has actually been filmed six times. There were two silent versions in 1907 and 1925, the famous Charlton Heston epic in 1959, a cartoon featuring Heston’s voice in 2003, and a more recent TV mini-series and movie remake. The titular character has his life turned upside down in various encounters with Jesus, eventually witnessing his crucifixion.

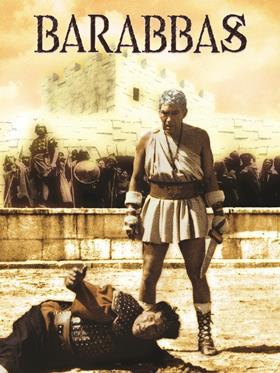

Barabbas

The success of Charlton Heston’s 1959 masterpiece meant another side-character epic was bound to follow quickly behind. A story about the criminal released in Jesus’ place, it imagines Anthony Quinn’s Barabbas returning to a life of crime and spending 20 years in hard labour, all while he’s chained to a Christian. Even the world’s worst evangelist couldn’t lose in that situation, and so it proves; Barabbas finds redemption through martyrdom on a cross, like a sort of biblical version of Final Destination.

Risen

A film possibly unique in that it begins with Jesus’ crucifixion; Risen follows Joseph Fiennes as the Roman soldier tasked with finding his allegedly resurrected body. Although initially convinced he’ll uncover a plot, Fiennes’ character witnesses the risen Christ’s ascension, and realises his whole mission is destined to end in failure.

See also…The Robe – a film about the Roman legion responsible for the crucifixion which is bizarrely a prequel to Demetrius and the Gladiators; Mary Magdalene, the 2018 biopic which seeks to correct harsher readings of the character, and Mel Brooks’ History of the World, Part 1, where Jesus and his disciples are served by Brooks’ pushy waiter at the Last Supper.

No comments yet