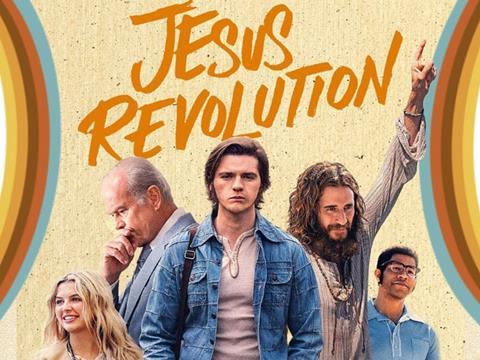

Jesus Revolution has taken $40m at the box office, making it highest-grossing film released by the studio Lionsgate since 2019. Andrew Whitman traces the history that inspired the movie

It was 1967, the year of the Summer of Love and the hippy movement was in full swing. Four years earlier, JFK had been assassinated. Protests were raging against the Vietnam War. The Beatles had just released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – the garish myriad of personalities of the album artwork a snapshot of the social upheaval of the era.

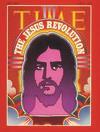

In the thick of this, the seed of the Jesus People Movement was beginning to germinate. The ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ counterculture was discovering a new way to live as many hippies began to embrace the gospel. Within four years ‘The Jesus Revolution’ would be Time magazine’s front cover.

Now that the Jesus Revolution movie, which stars Kelsey Grammer is taking the US box office by storm with its depiction of what happened on those Californian beaches, now seems a good time to reflect on a movement which leading scholar Larry Eskridge estimates saw at least 250,000 people become Christians. The Jesus People Movement has been dubbed the last great American revival, yet the UK also felt its impact in a variety of ways.

From the charismatic Church networks it birthed to contemporary worship styles, the story of the Jesus People has shaped the UK evangelical Church. Indeed, this very magazine had its first incarnation as Buzz, birthed as a response to the emerging youth and music culture of the 60s, and featuring the Jesus People Movement prominently.

Summer of love

1967 was also the year that Scott McKenzie’s ‘If you’re going to San Francisco’ had prominent radio airplay.

Ted and Liz Wise were early adopters of the hippy revival in San Francisco that year. Ted was an arty beatnik, grafting on yachts and tripping out on drug highs. Meanwhile, Liz was a regular at the conservative First Baptist Church of Mill Valley (alongside her dope lifestyle). Reading the New Testament Ted says, “Jesus knocked me off my metaphysical ass!” Then, following a bad trip on LSD in early 1965, he responded publicly to a gospel invitation at Liz’s church.

Ted and Liz were soon spreading the word to their contemporaries yet, despite their best efforts to evangelise hippies through their more traditional church, they eventually pioneered an independent Christian commune, The Living Room, in Haight-Ashbury in spring 1967. Located in a 20 foot by 40 foot storefront, they offered food, rest and gospel chat. By the following year they were seeing 20 or more people making commitments to Jesus each week.

The revival was spreading rapidly and spontaneously, and soon found its way to Britain.

Meanwhile, Hare Krishna devotee Dave Hoyt had a revelation of Jesus’ uniqueness. Mentored by theological student Kent Philpott, together they teamed up in evangelism and saw hundreds come to faith. Further down the coast in Costa Mesa, Chuck Smith’s Calvary Chapel exploded with growth. Five hundred new converts were baptised each month at Pirate’s Cove on the Pacific coast, as the church embraced a wave of hairy, hippy youth turning to Jesus.

Lonesome Stone

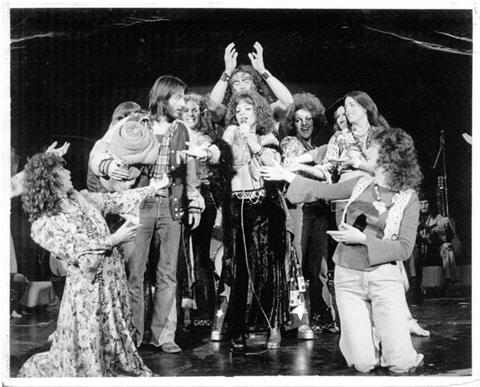

Six years later my own story intersected with the movement that first emerged from San Francisco. I was a 20-year-old farmer’s son and middle-of-the-road hippy, studying economics at University of Leeds. My younger brother and sister were brand-new Christians. They dragged me along to the penultimate performance of a Christian rock musical called Lonesome Stone on August Bank Holiday, 1973. I was utterly magnetised by Jesus and his death for me.

A suitably named cast member called Christian prayed with me after the performance, and I felt like God had totally cleaned me up inside. Christian then posted me duplicated scripture sheets and handwritten letters to help me grow as a new disciple. I aspired to join his Jesus Family community after graduation.

The Lonesome Stone musical which changed the course of my life had its roots in another branch of the Jesus People Movement on the west coast of the USA. Disaffected hippies Jim and Sue Palosaari had been powerfully converted at a tent revival, Jim visibly shook and clung to a tent pole as preacher Russell Griggs made his appeal.

They eventually ended up in Jim’s native Milwaukee, where they pioneered the Jesus Christ Power House with five new believers, and launched rock band The Sheep. By late 1971 the community had more than 150 members, but the following year Jim and Sue, along with two dozen others, travelled to Europe.

While roaming around Germany famished, cash-poor, and trying to sell a drum kit at Lautzenhausen’s US Air Force base, they received a surprise telegram. Christian businessman Kenneth Frampton wrote: “Come to England. Posthaste. Money no object.” He provided two communal houses and a coffeehouse for them in south London. With his backing they launched Lonesome Stone at the Rainbow Theatre in London in 1973. A parable of their combined experiences, it was the story of a hippy coming to know Jesus.

The Jesus People Movement in the UK was diverse, decentralised and often controversial. Early on there were three separate incarnations where Jesus’ name featured prominently, the first one imported, the latter two home-grown.

The Jesus Family

Radical American group the Children of God made their base in Bromley in July 1971 at Kenneth Frampton’s invitation. Frampton quickly severed ties, however, after realising they were a cult, subsequently alleged to practise mind control, religious prostitution, open marriages and child abuse.

Successors of Frampton’s backing, Jim and Sue Palosaari came to Britain in November 1972 with the Jesus Family. They were hot on street witnessing but Lonesome Stone was their main outreach vehicle.

Following London, the show played in Manchester’s rough Wythenshawe estate for four weeks. Afterwards, the only Jesus Family commune outside London was established in an abandoned rectory in Stockport. In September 1974 the American contingent returned home, and the remnant morphed into a Newfrontiers fellowship, eventually called Beulah Family Church.

The Jesus Family shared most marks of the Jesus People Movement, but tried to get new Jesus-followers to settle in local churches rather than forming separate communities.

The Jesus Army

The Bugbrooke (Baptist) Fellowship in Northamptonshire, founded in 1805, was led into renewal in the 1960s by eccentric pastor Noel Stanton. Soon afterwards, in 1971, they were inspired by the American Jesus People phenomena when cross-carrying evangelist Arthur Blessitt hit town, witnessing and offering Jesus stickers. They renamed themselves the Jesus Army in April 1987, with 800 people involved locally.

The hairy, bell bottom-wearing believers of Bugbrooke were aiming to model the first-century Church as they lived together in communal houses across Northamptonshire. Latterly the church became part of the Evangelical Alliance, though they were often perceived as cult-like in the 70s and 80s for their insistence on separation from the world.

Jesus Liberation Front

The third spin off from the Jesus People was the Hemel Hempsteadbased Jesus Liberation Front, launched in the summer of 1971 by Geoff Bone and Chris Boxall.

Street evangelism and an open home quickly meant 40 young people gathering regularly. An advert in Buzz magazine drew 600 replies. A team also joined Youth With A Mission (YWAM) in reaching out at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Again, the 3,000 nationwide members modelled themselves intentionally on the firstcentury Church. The group displayed many of the Californian Jesus Movement’s marks, experimenting unsuccessfully with community living, but also encouraging members to commit to local churches.

In July 1972, Geoff Bone was asked by Arthur Blesssitt to fly to Belfast to discuss new believers’ follow-up. At Watford Junction, hurrying for the appropriate Gatwick train, he fell between the platform and carriage, subsequently having both legs amputated. Amazingly, he was discharged from hospital five weeks later.

He finally left the Jesus Liberation Front in the mid 1970s due to domestic difficulties. Geoff’s current home-based mission is providing wheelchairs for amputees and resourcing his Facebook community.

Music and evangelism

Elsewhere in Britain, the Jesus People Movement was birthing other youth initiatives.

Musical Gospel Outreach was formed by three friends, Peter Meadows, David Payne and Geoff Shearn in 1965 to utilise contemporary music evangelistically, its newsletter soon becoming Buzz. Later, Christian bands such as the country-rock Mighty Flyers (part of the Manchester Jesus Family) gained strong followings.

Parachurch groups including Youth For Christ and Operation Mobilisation empowered many young people for mission, while Campus Crusade for Christ built on the Jesus People momentum by training a massive 30,000 people in evangelism at Spree 73. The Greenbelt Festival, encouraging creative Christian engagement with the world, was pioneered by Jim Palosaari and musician James Holloway in 1974: the former famously saying to the latter, “If you find yourself a field, you’ve got yourself a festival!”

Calvary Chapel, Costa Mesa was at the epicenter of the hippy revival

The UK also received huge inspiration from the American movement. Three successive and connected generations of ‘new paradigm churches’ have made significant waves here in Britain.

Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa was at the epicentre of the west coast revival, mainly due to the combination of Chuck Smith’s Bible teaching with Lonnie Frisbee’s signs-and-wonders evangelism. Surfers, dropouts and hippies would become future leaders in hundreds of other Calvary chapel church plants. The first of 38 presentday British Calvary churches – Church on the Way – was planted in a Bradford living room in 1978.

The Vineyard churches, led by John Wimber, also owed much to the Jesus People Movement. They had a formative moment on Mother’s Day 1980, when Lonnie Frisbee famously concluded his message by calling out, “Come Holy Spirit!” with dramatic effect. In the mid-80s, John and Ellie Mumford trained at Wimber’s Anaheim church, coming home in 1987 to plant the first British Vineyard in Richmond, Surrey.

More recently, Bill Johnson, who pastors Bethel Church in Redding, California, has had a strong influence on the charismatic wing of the British Church, through his Global Legacy movement and the European Leaders Advance conference in Harrogate. Three senior leaders, Kris Vallotton and Steve and Wendy Backlund all trace their spiritual lineage back to the Jesus People days.

The UK’s Jesus Liberation Front was largely inspired by the articulate Jack Sparks’ Christian Liberation Front in Berkeley, California. Enigmatic musical troubadour Larry Norman, famous for his anthem ‘I wish we’d all been ready’, was based in Britain after 1971, recording Only Visiting This Planet with legendary Beatles producer George Martin in London the following year.

Jimmy and Carol Owens’ Jesus People Movement-inspired musicals Come Together and If My People performed to full houses at the Royal Albert Hall. Bible teacher Hal Lindsey’s end-times book The Late Great Planet Earth and David Wilkerson’s story The Cross and the Switchblade were read voraciously and widely. Moishe Rosen’s evangelistic Jews for Jesus emerged from the Jesus People Movement in San Francisco in 1973, their current British base being in north London.

Last but not least, Sunset Strip minister Arthur Blessitt “turned people on to Jesus”, while carrying his cross the length and breadth of Britain, having particular evangelistic impact upon London’s historic Westminster Chapel.

The birth of modern worship

Whatever its localised expressions, the Jesus People Movement eventually permeated Christian culture in Britain through the music it brought with it.

Pete Ward, professor of ecclesiology and ethnography at Durham University, claims that the primary influence of the Jesus People Movement in the UK was a change of style: “The effect of the Jesus Movement was to breathe new life into the Church based on the appropriation of aspects of youth culture.” Such culture involved widespread changes in worship style. Out with the hymn-sandwich and in with the (previously sinful) guitar. This was largely the product of the movement’s informal style and the contemporary Christian music it generated.

Recently, the original editor of Buzz, Peter Meadows, spoke encouragingly about a three-fold impact the Californian movement had on Britain: Firstly, it shaped the lives of influential British Christians who went to the States to “look, see” (bringing back musicians like Larry Norman). Secondly, its Pentecostal roots, Californian laid-backness, and lack of religiosity poured more fuel on the charismatic renewal. And thirdly, Meadows says, “It lifted the morale and enthusiasm of the younger generation in the UK churches who, at last, had vivid examples of God at work in the world beyond the Church and in their own culture”.

The young radicals who found faith in the Jesus People Movement are now old enough to be entitled to free bus passes (and probably sport a lot less hair, too). And the movement itself only really burned brightly for as long as the hippy culture was with us. Yet its influence, like the youth counterculture it was part of, has shaped much of the evangelical Church today. Something special was birthed in 1967. It was the Summer of Love that turned into a lifetime of love for so many.

Andrew Whitman is currently engaged in writing a book on the impact of the Jesus People Movement on us here in the UK, and its revival legacy today. To find out more, see his dedicated website jesuspeoplerevivaluk.com

No comments yet