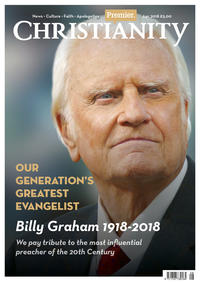

Billy Graham was one of the most important Christian leaders of the twentieth century, and possibly the most important evangelical leader in history.

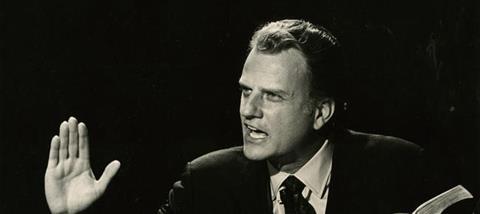

Graham preached to millions in a career that spanned over 60 years. The deep-voiced Southern Baptist preacher had talent and theatrical flair, yet his success was based on the simplicity of his gospel altar calls. His audiences were invited just to come forward, repent of their sins and invite Jesus into their life.

Millions responded across the globe, walking up to the strains of the hymn ‘Just as I Am’.

Billy Graham was born William Franklin Graham Junior in November 1918 in the town of Charlotte, North Carolina, and was baptised into the Reformed Presbyterian Church. In 1934, after hearing an address by the evangelist Mordecai Ham, the 16 year-old Graham made a personal commitment to Christ. Graham initially attended Bob Jones University, then Bob Jones College and by many accounts a grim, forbidding place. Bob Jones University was later to boycott Graham’s crusades, accusing him of welcoming ‘false teachers’ – Graham always strived for ecumenical support for his campaigns.

In 1937, Graham persuaded his parents that he should transfer to the Florida Bible Institute (FBI) where he graduated in 1940. It was here that Graham became a convinced Baptist, and was baptised by full immersion twice – once at the FBI, and again by the Southern Baptist leader Cecil Underwood. In 1940, Graham transferred to Wheaton College, Illinois, where he took a second BA, this time in anthropology.

It was while at Wheaton that Graham met Ruth Bell, the daughter of Presbyterian missionaries to China. Bell had no intention of marrying, and had imagined herself as an ‘old maid’ doing missions in China. But she was immediately drawn to Graham’s energy, charisma and humble devotion to God. They married in 1943, just after graduation. Ruth, who died in 2007 at the age of 87, was Graham’s soul mate and closest spiritual companion. She could be tough on him. Graham liked to joke that, when he had been considering running for the Presidency, Ruth had said that she didn’t think that the American public would take to a divorced President. The implication was clear. From 1945, the Grahams had settled in Montreat, North Carolina. They had five children: Virginia Leftwich, Anne Morrow, Ruth Bell, William Franklin, and Nelson Edman.

Crusades

One of the first positions Graham held after college was president of Youth for Christ. Traveling around America and Europe as the Youth for Christ representative gave Graham insights which would later serve him well in his ‘crusades’. In 1947, Graham began to plan his own evangelistic campaigns. At his first major crusade, in Los Angeles in 1949, figures such as the former gang member James Arthur Vaus Junior and the teenage delinquent and Olympic athlete Lou Zamperini came forward to receive Christ. Zamperini was impressed by the ‘clean-cut all-American type’ Graham.

The extraordinary response to the Los Angeles crusade famously led newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst to call on his editors to ‘puff Graham’ – ie build him up. The positive response of Hearst’s newspaper empire to the crusade meant it lasted five weeks longer than planned. Hearst’s sons even believed that Hearst – famously the model for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane – went to the crusades disguised in a wheelchair. Graham’s first major international crusade was in London in 1954, where he preached to thousands at the Harringey Arena in north London. Graham also had a private audience with Winston Churchill; according to Graham’s memoirs, Churchill had said: "I am a man without hope. Do you have any real hope?"

What was behind the success of the Billy Graham crusades? Many pointed to the ‘utter simplicity’ of Graham’s appeals, based on a number of carefully chosen biblical texts. Others were more suspicious of Graham’s methods, seeing them as overly emotive.

Some saw him as a salesman, using modern techniques of PR and publicity to create a buzz around the crusades. Graham defended the style of the rallies. "In every other area of life, we take for granted publicity, bigness, modern techniques", he told a reporter in 1956, "why should not the church employ some of these methods?" Still others within the fundamentalist community in America felt that Graham was too ‘liberal’ or ‘modernistic’.

Graham was clear on his position; if ‘fundamentalist’ meant an orthodox belief in Scripture, the atoning work of Christ, and his physical resurrection, then Graham was a fundamentalist. If ‘fundamentalism’ referred to what he called ‘a series of reactionary positions’ defined against liberalism, however, then Graham would have no part of it.

Politics

Politically, Graham avoided controversies, and regretted some of his earlier involvement in political questions. He had been outspoken as a young man against communism and socialism. Graham came to believe that Christian ministry was strongest when it was identified with neither Left nor Right.

Although he was firm friends with Republican Presidents Richard Nixon and both Presidents Bush, Graham was actually a card-carrying member of the Democratic party. Graham met every American President from Harry Truman to Barack Obama. But Graham felt that political questions were essentially a distraction for the church, although he encouraged Christians to enter politics. Graham never courted the powerful for reward; as the academic Stephen Winzenburg has said, ‘Graham made a conscious effort to befriend people in power so he could gain access to bigger crowds’.

Graham came to believe that Christian ministry was strongest when it was identified with neither Left nor Right

Graham soon became a celebrity, and was well-suited to the world of film and television, with his tall, striking frame and his clean-cut good looks. His distinctive voice – fiery and dramatic as a younger man – mellowed with age. Yet even well into his eighties, Graham would practice his vocal exercises every day like an opera singer. Prayer was the engine of Billy Graham’s ministry – prayer each day, every day, morning and evening.

Every morning began the same way, with Graham praying for the strength to complete the work God had given him. It could be said that Graham was simply an old-style evangelist, in the mould of Dwight L. Moody, John Wesley and George Whitefield. It was the world that had changed – a world of mass-media and global communication. Harold Bloom called Graham ‘the Pope of Protestant America’, and although one could argue the point, one could see what he was getting at. In terms of reach and influence, Graham’s peers were John Paul II and Mother Theresa.

Graham went behind what was then the Iron Curtain to preach the gospel in Communist Russia, Poland and Hungary. He met Gorbachev and Yeltsin, and in 1978 was invited to Krakow by the Polish bishop Karol Woytyla, later to be Pope John Paul II. Woytyla was the only Catholic figure to welcome Graham, and the two men had planned to have tea together, but by the time Graham’s plane landed, Woytyla had gone to Rome to accept the pontificate.

Graham’s 1982 visit to the Soviet Union was widely criticised in the United States, the New York Times among others accusing him of denying Soviet repression. Graham was outspoken in favour of peace – the visit took place at the height of the Cold War – and he also met with Russian Christian leaders.

The culmination of Graham’s groundwork behind the Iron Curtain was his extraordinary Moscow crusade in 1992. On the first night in Moscow almost 11,000 people had pledged commitment, on the second night, almost 13,000. The national and international crusades took it out of him; preaching at Madison Square Gardens in New York City in the 1950s, he lost 30 pounds in weight.

Everyone who met Graham talked of his humility, and he always tried to deflect attention from himself and onto Christ. When the million-dollar Billy Graham Library opened in 2007, Graham said that its purpose was ‘to please the Lord and to honor Jesus, not to see me or to think of me’. At its opening, the preacher complained that the ceremony gave the public ‘too much Billy Graham’.

Graham always worried that too much focus on him as a personality would weaken his message, compromise his integrity. It was an integrity he worked hard to maintain. Graham and his senior advisers pledged to avoid any situation where they might be accused of financial impropriety or other scandalous behaviour. Graham famously never met with any woman alone other than his wife. He also founded the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability, and was ultra-scrupulous about the way he raised funds.

Controversy

But Graham’s life and legacy were not without controversy. Some, for example, accused him of not taking a firm enough stand against segregation during the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. Although Graham was critical of the Jim Crow laws that existed in the South from the early 1950s, many thought his stance was not provocative enough. ‘He stressed individual conversion over political change,’ wrote the New York Times, ‘supporting legal reforms in lukewarm terms while insisting that only the Gospel could really improve race relations’.

Certainly, Graham’s emphasis was on the coming kingdom, but it is hard to argue that he was a reactionary figure. He staged desegregated rallies, and got to know Martin Luther King as a personal friend, inviting him to preach at one of his rallies. Dr King said that Graham’s help had been instrumental in the success of his campaigns: ‘Had it not been for the ministry of my good friend, Dr. Billy Graham, my work in the civil rights movement would not have been as successful as it has been’.

Graham was also criticised as apparently anti-semitic remarks he made in conversation with President Nixon in 1972 were found on tape. When confronted with the remarks, Graham was contrite. ‘I deeply regret comments I apparently made in an Oval Office conversation with President Nixon and H.R. Haldeman some 30 years ago’, he said. ‘They do not reflect my views and I sincerely apologize for any offense caused by the remarks.’ He added: ‘I realise that much of my life has been a pilgrimage - constantly learning, changing, growing and maturing. I have come to see in deeper ways some of the implications of my faith and message, not the least of which is in the area of human rights and racial and ethnic understanding.’

Legacy

Graham’s son Franklin Graham gradually took over the running of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (he was made CEO in 2000). Franklin Graham has proved readier to be involved in politics than his father, and at times has been roundly criticised for his controversial statements on Islam. His description of Islam as ‘a very evil and wicked religion’ were ‘lovingly rebuked’ by other evangelical leaders. He also found himself in hot water when he appeared to give credence to ‘birther’ theories about President Obama’s parentage, hinting that Obama might not be a Christian.

Other projects that Billy Graham was involved in included the founding of Christianity Today magazine in 1955. The magazine was intended as a focus for the evangelical community within the United States. Graham was also instrumental in the founding of the Lausanne Movement, which helped to unite evangelical Christians across the world. The first International Congress on World Evangelisation was convened by Graham in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1974. Many evangelicals consider the Lausanne movement, and the accompanying Lausanne covenant, as re-emphasising the need for social justice and care for the poor within evangelical Protestantism.

"I have never converted anybody. Only Christ can change the course of a man’s life" - Billy Graham

Along with other leading Christian figures such as John Stott, Francis Shaeffer and Carl Henry, Graham stressed the need for the Lausanne movement to understand the contemporary world. Lausanne attempted to weld together a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of different cultures and an emphasis on social action, with an unflinching commitment to historic, biblical Christianity. In the covenant’s own words: ‘We affirm that God is both the Creator and the Judge of all people. We therefore should share his concern for justice and reconciliation throughout human society and for the liberation of men and women from every kind of oppression.’

Final years

In 1992, Graham announced that he had Parkinson’s disease, and he began to cut back on his full schedule. In 2006, Graham preached at his last crusade in New York City. The old showmanship was still in force; Jon Meacham, former managing editor of the US magazine Newsweek, who was watching the crusade, talked of the ‘great stagecraft’ of the event. Meacham was impressed by the then 87-year old preacher’s ability to ‘convince an audience of a reality we cannot see ourselves’.

Meacher commented that, although Graham’s message might seem ‘sectarian’, it was nonetheless a message that ‘opens up the possibility of grace for everyone’. It was the universality of Graham’s appeal that made him so successful: white and black, Democrat or Republican, all could relate to his simple, gentle charisma.

In more recent years, Graham retired from public ministry and has battled Parkinson's, cancer and pneumonia. His son Franklin told Premier last month, "He’s just tired; he doesn’t say much anymore – he’s gone very quiet. We’re planning to celebrate his birthday but I’m not sure he’ll care. He told us when he was 90 he was going to live to be 95 – I didn’t believe him."

Graham has lived a long and fruitful life. He died today, age 99 - just seven months shy of his one hundredth birthday. He will be remembered primarily for influencing millions of people across the world. Hundreds of thousands of people will today mourn a man who played a significant role in their coming to Christ.

Yet for Graham it was always God’s work, not his. "I have never converted anybody," he said in 1956. "Only Christ can change the course of a man’s life". His daily prayers were simple: ‘Help me, Lord’. Once, when asked what he thought when he saw a videotape of himself preaching, he replied: ‘I think of him as another person speaking, because the spirit of God begins to speak to me through him.’ That was classic Graham – he longed that he might disappear so that only God would be praised. He didn’t have his wish – he became a celebrity. But in terms of the advancement of Christianity, he is surely one of the key figures of our age.

David Barnes is a writer, critic and lecturer whose work has appeared in The Times and The Guardian. He studied for a Masters’ and then a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London and currently resides in north London.