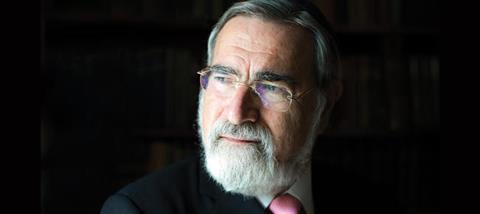

I have recently been listening to a series on Radio 4 called Morality in the 21st Century, presented by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks.

The programmes do an excellent job of highlighting the contemporary collapse of a shared moral purpose, especially in the West. They show that left to the market (capitalism) or to the mob (cultural Marxism) there is no absolute morality and careful thinkers realise that the trajectory we are now on as a result of this is terrifying.

Regaining a sense of responsibility

Lord Sacks interviews many experts in social science, economics and psychology. One of these is Jordan Peterson. He has become immensely popular in the last year, including among many Christians, for his passionate plea that everybody, especially men, needs to take more responsibility for themselves and through that find meaning and purpose in life.

Much of what Peterson says shows a healthy respect for biblical narrative and values. He has been great at pointing out the bankruptcy of a philosophy that claims that individual happiness is the goal of life. He shows that this does not work; it sets unachievable goals, is destructive to society and stifles progress. Peterson thinks that purpose is more important than happiness. But ultimately his god is one of individual satisfaction through finding meaning and purpose. It is basically a utilitarian argument for morality. This won’t work either because there is no agreement about what constitutes good, responsible behaviour.

Fair Trade

Later in the series the economist Noreena Hertz predicts that ultimately the owners of the means of production will use artificial intelligence to do most of our work. And when that happens, what will remain for the rest of us? Her best hope is that the market might act morally and purchase things that are made in ways that are morally good. She takes some encouragement from the growth of ethical investments. But who defines good ethics? What philosophy out there values human life over market forces or mob rule?

Humanism

In another episode Sacks speaks with scientist and philosopher Steven Pinker. He agrees with the Rabbi that religion has some benefit in giving us stories and a sense of community. But in his view we have to evaluate the value of any religious teaching by the higher authority of humanism. He cheerfully believes that things can be shown to be right or wrong. The humanist definition of goodness is about what makes humans prosper, treating other people as we would expect to be treated and using power and knowledge for the benefit of the community to improve the human condition. But amazingly for such an intelligent man, he has no realisation that he might have inherited those values from some higher authority. He gives no basis to prove that those are, in fact, good values, assuming it to be self-evident. Nor does he engage with the reality that most of us do not live up to these things; yet another bankrupt philosophy.

The author with the authority

Love and morality must have a source – an outside authority – or they are arbitrary and meaningless. A philosophy that says we should be loving and do the least harm to the least number of people, but includes no authoritative definition of love and harm, carries no weight.

And so, throughout the series the experts mourn the loss of morality and express their desperate desire that somehow there could be more of it. It is a thoroughly depressing series unless the listener has gospel hope.

We do have such a hope because the very concept of morality shows us that God exists. The general desire for morality is evidence of a higher authority. If morality is transcendental (something solid and real but beyond and outside of us) it points us to the reality of God. He made people in his image and our concept of morality reflects something of his nature. If God does not exist, then objective moral values do not exist either. But we instinctively know that objective values do exist and thus we must conclude that God exists.

Therefore we can have hope, because we can introduce people to the author of morality, the one with authority to define what is good. He is the Saviour who will take away the guilt of our failure to act morally and give our lives true meaning and purpose.

Now why won’t the BBC give us a 15-part series on that?

Graham Nicholls is the Director of Affinity. This article first appeared on affinity.org.uk and is used by permission