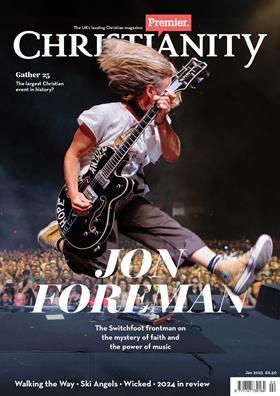

Switchfoot’s lead singer on why his Christian faith is still a mystery, music that breaks down barriers and throwing a worldwide 20th birthday party for his band’s biggest album

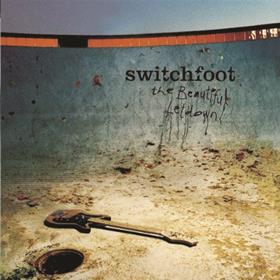

Switchfoot doesn’t make Christian music. But their breakthrough record The Beautiful Letdown is unquestionably one of the greatest Christian albums of all time.

This is the paradox at the heart of this hugely successful San Diego based band. On one hand, their frontman Jon Foreman is a pastor’s son who has written songs based on Psalms (‘The house of God forever’) and penned confessional lyrics such as “The day I lost myself / Was the day that I found God”. On the other, he is adamant that he doesn’t write songs for Christians and despises the sacred-secular divide, dismissing the entire category of ‘Christian music’ as a misnomer. He once memorably quipped: “Christ didn’t come and die for my songs.”

I catch Jon Foreman, 48, in a typically philosophical mood (he casually cites Kierkegaard and refers to his fellow human beings as “these embodied souls” during our conversation). We speak just a few days before the band’s sold-out show at Electric Brixton, London - part of the world tour which will see them play The Beautiful Letdown in its entirety.

It’s quite the 20th birthday party for the record, which sold 3 million copies and brought the band international fame during the early noughties. You don’t need to be a fan to have heard the iconic opening guitar riff from ‘Meant to live’ (it featured on the soundtrack for Spider Man 2), or their stunning, emotion-stirring pop ballad ‘Dare you to move’ (it was in the Mandy Moore movie A Walk to Remember).

Love is the power that changes us. Dogma rarely changes my mind

I was among those who gathered at Brixton to enjoy live performances of all eleven songs, plus a handful of extras, from a band which still oozes energy and charisma. At the end of the night I stuck around with a few others, standing on a street corner and eagerly awaiting a message from Foreman’s Instagram account. Eventually, it came: “London? What a night! Aftershow out back in a few?” Cue a frantic rush to the back of the venue, where Foreman emerged with just an acoustic guitar and harmonica. Fighting the noise of the London streets, he sang his heart out – fans visibly delighted to witness his talents at such close proximity.

I noticed a Pentecostal church just down the street with a sign out front saying: “Worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness”. It was then that I realised - peel away the rock show, stage diving and power chords and that’s exactly what Foreman had been doing all night.

Tell me about your childhood and where faith first came into your life.

My dad is a pastor, so I grew up in church. He was also the guy who taught me how to play ‘Stairway to heaven’ when I got really into Led Zeppelin. To people who might not have grown up in church, that doesn’t seem odd. But Zeppelin was one of those bands that you did not listen to, so when I started playing it in the youth group, all the kids freaked out like: “No, no, you can’t do that. You can play U2, but not Zepplin.”

I think that exemplifies the way I grew up - not really seeing a delineation between sacred and secular but seeing all of the earth as God’s sacred playground.

That kind of binary thinking is evident in lots of places, including US politics. But it happens in music too, when songs are labelled either ‘Christian’ or not.

Yeah, absolutely. And I find these labels are unhelpful. It turns faith into some sort of weird team sport.

I find Kierkegaard’s delineation between Christendom and the Church really helpful, because I feel like there’s the business of the Church - the things that we stamp as ‘Christian’ - and we sell them. The spirit of “they’re on our team” or “they’re not”. In many ways, it is unhelpful.

When I meet someone at a coffee shop, in a park, at a pub, these delineations of black or white, Republican or Democrat, Christian or atheist, are extremely unhelpful in connecting with the heart of who we really are.

I think that’s the beauty of a song - it doesn’t force you to declare your identity before you listen. It is agnostic in that regard. It allows you to take the song for what it is. It sneaks past the watchful dragons of religion - whatever your religion might be. That’s what I love about music; we can all find ourselves in a song, lose ourselves in a song and, maybe by the time the song’s over, we’ve become a different person.

Was there a moment when faith became real to you, not just something your parents believed?

That’s a great question. I do think the overarching story in Christian circles is often a ‘before and after’ story. “I was blind, but now I see.” And it is that, but it’s also a continuing process.

In every relationship there’s unfolding and growing. To think that I’ve ever completely figured out my wife would be a misnomer. Or, as a surfer, I think of the ocean. There’s never a moment where I can say: “I’ve got the ocean figured out.” The ocean will ever be a mystery, as it is with my faith.

How has your faith changed over time?

This particular season has been a season of wanting to reconnect with the simple truths of being loved by my maker. I look around at so much beauty that can’t be accounted for without the presence of some deity. I think that the faith leap for me is usually: Can this deity love and interact with myself? That’s where the faith journey begins for me most days.

What does church look like for you?

I grew up in Calvary Chapel and my parents were in the Jesus Movement. But now, it is a challenge, certainly, to stay connected when my job requires me to be gone most weekends of the year.

But church can happen anywhere - it’s not the building. We’ve had some incredible moments on the road. A Bible study with folks that come from a totally different understanding and have insights of their own - they’ve been some of my favourite moments of church in the past few years.

It’s 20 years since The Beautiful Letdown was released. Why did it resonate with so many people around the world?

It’s ironic that a song you write at three in the morning, when you’re wrestling with something and you feel like you’re alone in singing it, that’s the song somebody halfway across the planet [listens to and] says: “I know exactly what you mean.” That’s what I love about music - the connection that it affords us. I still don’t understand how it works, but I’m thankful for it.

Is there an overarching theme to the record?

There are layers to the title The Beautiful Letdown. As a band, it was a “beautiful letdown” to be signed to a major label and then subsequently dropped before the record ever came out. I think the Church is a beautiful letdown. I think I’m a beautiful letdown. I think that’s what confession is. It’s confessing the beauty, the pain, the heartache, and then moving forward.

The album encapsulates a lot of what we were dealing with at the time as a band. We were thinking: This is our last album. Let’s go out and make one more beautiful, honest record, and then we’ll go get day jobs.

When did you realise you were wrong, and that the band had suddenly become incredible successful?

It’s been a wild ride, because we have outlasted a lot of the musical trends that we never seemed to fit in with. I remember being on a radio show at Madison Square Garden alongside Destiny’s Child and Maroon 5. And there was a TV personality introducing the band before us - this guy named Donald Trump. I remember thinking that I didn’t belong. We played and everyone was singing along with their lighters out and cell phone lights on and I just felt gratitude. There’s been many moments like that over the years, where you feel like you’re part of something bigger than yourself.

A lot of your music has transcended the walls of the Church, and you have many non-Christian fans. As a songwriter, do your songs carry a spiritual message?

I went to a university where everyone was becoming doctors. There was an empirical mindset - materialist in the philosophical sense. I was one of the only Christians, and I loved it. Every night my roommate and I would have long conversations. He was a determinist. It’s a conversation you can have forever – determinist vs whether you have agency in the world. I think in many ways, I still write songs for my dormmates.

I was one of the only Christians at university. In many ways I still write songs for my dormmates

When I read the Gospels, I encounter this iconoclast who is so open with everyone, except for the religious establishment. He meets people where they’re at and loves them. Ultimately, love is the power that changes us. Dogma rarely changes minds. Statistics and rhetoric fall flat compared to helping me when I need it. Show up when I’m broken and hurt, give me your time and have an ear for me, and I’m ready to listen. There’s a binary spirit in our age where there’s no synthesis. There’s no ‘us’, there’s only you or me. That’s not the gospel.

Thousands of people who may have nothing in common come together at your shows and quite literally sing the same song. Do you recognise the power in that?

I do. Music is one of the last places where you can stand next to someone you completely disagree with, hold your hands in the air, hug, cry, weep, laugh together and leave with an understanding of how much we have in common. That’s a beautiful thing.

Most of your music isn’t designed for congregational worship, but occasionally you do write a song that can be used in that way. Have you ever thought about making a worship album?

Those songs exist because my wife asked for that album! I asked what she wanted for her birthday, and she said: “I want you to make a worship record.” So, I started figuring out Chris Tomlin songs, and she said: “No, not other people’s songs. I want you to write it.”

I think all music is worship. I think ‘worth-ship’ is what we do with our time, our energy, our thoughts. Music is an extension of that. Corporate church worship is something I grew up in, and because it felt so intrinsic, those are sometimes the hardest songs to write. Like: How do I enter into this from a place that feels real and genuine and also unique?

How would you describe your calling?

I think the embodied human rarely has one calling. I’m a father, a husband, a member of a community; I’m in a band. So, I think my calling is to be present to the multitude of places where I am.

Is that hard to do?

Exceptionally hard, especially with these devices and the ever-present omnipotence in our pocket. With a couple of clicks of a button, we can be anywhere and know anything. It’s really hard to be present to the particulars that are around us.

How do you counter that?

I really like books. I love feeling the paper, dog-earing and underlining. I love writing in journals. For any songwriters out there, I challenge you: instead of writing on an iPhone, write with pen and paper. I feel like it integrates a different portion of your brain. Shutting the phone off, putting it away, not having it out at dinner – these are all things that can help.

When I was coming up, the way we found out about music was magazines - NME or Rolling Stone. Now, every single music maker is their own advertising agency, for better and worse. You could call it a necessary evil, but the evil is right there! Many times, I’ll try and turn my phone off for the week and not feel like it’s a part of me.

There’s a culture of self-promotion on social media – you see people posting videos promoting themselves or their products. Is there a tension between needing to advertise your work to an audience, but also pursuing humility as a Christian?

I think this Insta-brag kind of culture is part of a larger question of who we are as humans, who we’re becoming and what we want to pass on to our children. I think about that all the time. I’ve got a little girl and a little boy. When I was growing up in the 90s, it was simpler. We got into trouble with skateboards - things that feel benign compared to the internet.

I don’t pretend to have everything figured out, but I think the struggle and wrestling is valid and needed.

You’ve said before that you write songs about things you don’t understand - God, girls and politics. Does the process help you better understand God?

Songwriting absolutely helps. Many times, my wife will say that the songs help her understand what’s been on my mind.

We moved around a lot when I was a kid. After one move, I had a really hard time making friends. It was a dark season. I started stuttering. Music, at that moment, was a place where I could communicate clearly. The song felt truer than something I could say in prose or conversation.

Songs, for me, have been a vehicle where I can begin with darkness and aim for the light.

Switchfoot’s The Beautiful Letdown (Our Version) and Jon Foreman’s In Bloom are available now.

To hear the full interview listen to ‘The Profile’ podcast premierchristianity.com/theprofile

No comments yet