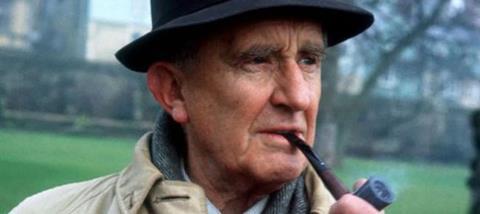

With a twinkle in his eyes J.R.R. Tolkien saw himself very much as a Hobbit, and more seriously as a Christian.

His Roman Catholic faith was orthodox, which he felt gave him immense common ground with those of other denominations, such as his Ulster friend and colleague, CS Lewis. The pair disagreed over remarriage, cremation of the body and popularizing theology, but nevertheless remained friends for nearly 40 years, and very close friends for a great deal of that time. There is no doubt that Tolkien sought friends who shared his faith, even if they did not share his churchmanship.

In a letter, Tolkien aired his view that The Lord of the Rings was a "fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision"; that is, it was endued with his religious insights. He was delighted when a priest wrote to him that what he had read of the book had “a positive compatibility with the order of Grace’, likening the beauty of Galadriel to the Virgin Mary.

Tolkien regarded any such religious elements as being inherent in the story rather than being explicit. He felt that openly religious references would mar the impact and consistency of the story upon the reader.

The Fall of Gondolin

Perhaps the last of the books of Tolkien that have been published since his death will be The Fall of Gondolin, which was released two weeks ago.

It is in fact the first story he wrote and already carried a latent Christianity from his deep beliefs. The memories of The Battle of the Somme, which took the lives of two close friends, were fresh in his mind, and no doubt in his nightmares.

The destruction of the beautiful city of Gondolin by cruel and demonic forces led by the Satanic Morgoth describes terrifying weapons inspired by the first use of tanks and other deadly features of mass slaughter in the Battle of the Somme. Tolkien’s imagery of the conflict of good and evil is realistic even in how he presents hope in providence and hints at future redemption in his stories.

The familiar The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are set in the third age of his invented world of Middle-earth. He created many stories in his deeply realised world features. The Silmarillion is about the First Age of Middle-earth. Tolkien sets it in a pre-Christian age. According to Paul Kocher, its theme is "Morgoth’s implanting of the seeds of evil in the hearts of Elves and Men, which will bear evil fruit until the last days". In this outworking of the theme of evil, Sauron, who followed Morgoth, plays a crucial role in the Ages of the world of Middle-earth.

Christian meaning

An important element in the embodiment of Christian meaning in Tolkien’s fiction comes from his theory of ‘sub-creation’. The Silmarillion, The Lord of the Rings, and even The Hobbit are attempts at sub-creation (worlds created in the image of God’s creation), and as such try to "survey the depths of space and time". Tolkien’s theme is to reveal the essential meaning behind human history and the image of God in humans. Like the biblical book of Revelation, he is concerned to bring hope and consolation in dark and difficult days.

To appreciate the freshness and depth of Christian meaning in Tolkien’s work, he can be compared with John Milton, the author of the epic poem, Paradise Lost. Both Tolkien’s fiction and Milton’s great work are a study of evil, and a defence of God’s ways to humankind. In Tolkien, Morgoth, and his servant Sauron, are of central importance, as Satan is in Paradise Lost. The very title of Tolkien’s popular trilogy refers to Sauron, the dark lord of the Rings. As also in Milton’s work, the theme of fall from grace (disgrace) into sin or chosen wickedness predominates.

Clyde S. Kilby, an evangelical scholar, was able to spend much of the summer of 1966 working with Tolkien on the unfinished The Silmarillion, and asked him many questions concerning the underlying meanings of his work.

In his little book, Tolkien and the Silmarillion, Kilby describes him as a Tridentine Roman Catholic, a convinced supernaturalist. He believed in a personal yet infinite God who could answer prayer. He and his wife Edith believed that one of their sons had been healed of a heart complaint. Talking to Tolkien had been a major factor in the conversion of C.S. Lewis to Christianity.

Although the name of God doesn’t as such appear in Tolkien’s fiction (there he is called Ilúvatar—the all-father), it is full of Christian meaning. Tolkien spoke to Kilby, for instance, of the invocations to the angelic power, Elbereth Gilthoniel. Tolkien deliberately avoided explicit references to religion. His interest was in theology, philosophy and cosmology – the elements which make Christianity a world outlook rather than merely a matter of private and public religious experience. It was part of Tolkien’s view of humankind as sub-creator, in God’s image, that human sub-creations would be like all possible worlds created by God in having a moral and religious character or ‘nature’.

Before and since Tolkien’s death there have been numerous articles and books on the meaning of his fiction. Kilby records Tolkien’s favourable reaction to an essay sent him from Australia, concerned with the themes of kingship, priesthood and prophecy in The Lord of the Rings . He endorsed the spirit of the essay, in finding Christian meaning in his work, even though, as he remarked, it displayed the tendency of such scholarly analysis to suggest that it was a conscious schema for him as he wrote.

He didn’t deliberately try to insert Christian meaning into his work – a point over which he disagreed with C.S. Lewis, in whose fantasy he felt the Christianity was too explicit. A fruitful way of considering Christian meaning in Tolkien is in terms of his commitment to a natural theology. C.S. Lewis, in his book, Miracles, emphasized the importance of presuppositions or our pre-understanding in approaching historical and natural events. Tolkien, on the contrary, finds real history and natural events a helpful guide to truth in themselves. Whereas traditional natural theology concentrates on the revelation of God in nature and cosmology, Tolkien particularly finds inevitable theology revealed in language and story. Lewis was not averse to this view.

The greatest story of all

In On Fairy Stories Tolkien finds the attributes of escape, recovery and consolation. Consolation, particularly, is loaded with Christian meaning, focused on the good news, the gospel. This structure of story is vindicated by the greatest story of all, told in the biblical gospels. This has the story qualities of escape, recovery and consolation, yet is, astoundingly, true in the real world, in actual human history.

As well as his natural theology, Tolkien was deeply inspired by, or at least found himself using parallels with, biblical imagery. These associations include biblical imagery of trees, the fall of humankind and some angels, the personification of Wisdom in Proverbs 8, and the biblical portrayal of heroism.

In a letter to W.H. Auden (in 1965), Tolkien commented on The Lord of the Rings in relation to Christian theology: "I don’t feel under any obligation to make my story fit with formalized Christian theology, though I actually intended it to be consonant with Christian thought and belief."

Colin Duriez has written a number of books on Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and their circle of friends, the Inklings. He has appeared on many related documentaries, including on the Extended Version DVD box set of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. His biography, J.R.R. Tolkien: The Making of a Legend, is published by Lion Hudson.

SPECIAL: Subscribe to Premier Christianity magazine for HALF PRICE (limited offer)