A House of Lords debate on assisted dying ended without a vote and will not become law without government backing, but the quality of peers’ contributions was widely praised.

The majority of Christian and other religious leaders spoke against Lord Falconer’s Assisted Dying Bill, which would allow doctors to prescribe a lethal dose of drugs to terminally ill patients who are believed to have fewer than six months to live.

Around 120 peers contributed to the debate, with an equal split between those in favour and those against. Those in favour argued that in certain circumstances it is cruel to keep people alive and in pain if they have a settled wish to die and are unable to commit suicide.

Prominent clergy broke ranks ahead of the debate, with former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr George Carey saying that the case of severely disabled Tony Nicklinson, whose long fight for the right to die ended with his death from natural causes, had resulted in a change of heart.

In an article for the Daily Mail, Carey wrote: ‘In strictly observing accepted teaching about the sanctity of life, the Church could actually be sanctioning anguish and pain; the very opposite of the Christian message.’

Archbishop Desmond Tutu also said that he revered the sanctity of life, but ‘not at any cost’, claiming that prolonging the life of the late Nelson Mandela had been an ‘affront’ to his dignity.

Methodist minister and former president of the Methodist Conference Baroness Richardson spoke out strongly in favour of the Bill. Like Tutu, she said that she believed in the sanctity of life and that the Bill’s protection for the vulnerable should be made as strong as possible.

However, she added: ‘If I am diagnosed with a terminal illness from which I will certainly die in a few months, I would wish to protect my family from having to watch me, from putting their lives on hold and making a rota to make sure that somebody is with me at all times.

‘I would want to protect them from having to bear my anger, frustration and sheer peevishness, which often accompanies pain. How much better it would be to be able to say goodbye, give thanks, forgive and heal resentments, and share the precious moment of death together, and not for me to be left out of the wake that will happen when I have died.’

The counterargument, expressed by many religious leaders, was that more effective palliative care is needed for those during the final stages of life. Those opposing the Bill also argued that it would be impossible to protect vulnerable people from feeling obliged to die to avoid becoming a burden. Fears of a slippery slope that would eventually lead to involuntary euthanasia were also expressed.

I see the Bill as a tremor, warning of a seismic change in our society

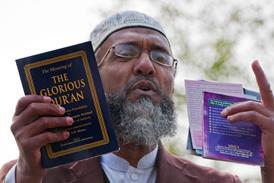

Ahead of the debate, a statement was released by 23 faith leaders including the archbishops of Canterbury and Wales and the senior Roman Catholic leader in England, Cardinal Vincent Nichols. Other Christian denominations contributed, along with those from the Muslim, Zoroastrian, Hindu, Jewish, Buddhist, Sikh and Jain faiths.

The statement said: ‘Every human life is of intrinsic value and ought to be affirmed and cherished. This is central to our laws and our social relationships; to undermine this in any way would be a grave error.

‘The Assisted Dying Bill would allow individuals to participate actively in ending others’ lives, in effect colluding in the judgement that they are of no further value. This is not the way forward for a compassionate and caring society.’

Archbishop of York, Dr John Sentamu, said: ‘Accepting the approach of death is not the attitude of passivity that we may think it to be. Dying well is the positive achievement of a task that belongs with our humanity. It is unlike all other tasks given to us in life, but it expresses the value that we set on life as no other approach to death can do.’

Former Lord Chancellor, Lord Mackay, also contributed to the debate. ‘We may feel strong today and may be able to weigh up issues with which we may be confronted,’ he said. ‘However, the devastating effect of serious illness can speedily make us vulnerable, so that although still possessed of mental capacity we become much more susceptible to influence than when in health.’

Former Bishop of Oxford, Lord Harries, added: ‘I fear dreadfully for the whole attitude of our society to the vulnerable and incapacitated. I see the Bill as a tremor, warning of a seismic change in our society towards those who require costly, arduous care day and night. I believe that we should stick to the present law, together with the sensible guidelines of the DPP.’

The sharp polarisation of opinion evident in the House of Lords indicates that its Bill’s passage is likely to be difficult. However, in a recent ruling on assisted suicide involving Nicklinson’s family, paralysed crash victim Paul Lamb and a stroke survivor known as ‘Martin’ in a bid to preserve his anonymity, the Supreme Court indicated that Parliament needed to clarify its view of how the law should operate. This means that government time might be made available at some stage.