Malaria causes 750,000 deaths in Africa every year. Christianity learns what is being done to combat it and Tony Blair highlights about the role churches can play

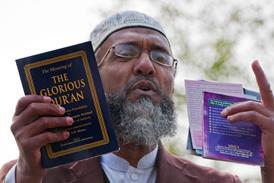

The setting sun casts long shadows across the village as a mother scoops up her two-year-old son, carries him into her hut and lays him on a makeshift bed. The little boy raises his head for a goodnight kiss, yawns and then wriggles under the thin blanket. A warm breeze ruffles his hair as his breathing gradually slows into the rhythmic pattern of sleep. All seems well. But a deadly threat is literally inches above the boy’s head. Unseen and unheard, a malarial mosquito has detected the presence of the child and, drawn like a magnet, it quickly lands on the boy’s uncovered arm. Injecting a mild anaesthetic through its hypodermic sharp beak means the boy’s slumber is undisturbed. A minute later, its stomach full of the boy’s blood, the insect flies off leaving behind a red swelling that will itch in the morning. But within the boy the seeds of malaria have been sown which will reap a bitter harvest of repeated raging fever. Yet another young African life is blighted barely after it has begun. Every year three quarters of a million people die from malaria in Africa. Stop and reread that last sentence again before you let your eyes and attention move on… A horrendous statistic – 750,000 people – the population of a large city like Birmingham, die every year as a consequence of malaria. What makes matters worse is the fact that this debilitating and often deadly infection could be forced off the planet – if we all got our act together. The good news is that Christians in Africa are at the heart of a campaign to spread vital information to every community on how they can reduce the rates of infection through following simple preventative measures. Local African churches are key transmitters of aid in many countries where corruption is rife. Churches are helping the fight against malaria by distributing nets, which offer protection from malaria-carrying mosquitoes, to adults and children as they sleep. Major aid agencies including Tearfund and World Vision have funded programmes to fight malaria. A charity solely dedicated to ending this disease, Malaria No More UK, has won the backing of Premier Radio, the majority shareholder in CCP Ltd, which publishes Christianity magazine, along with high profile figures including David Beckham and Tony Blair to get behind efforts to eradicate malaria. Talking exclusively to Christianity, the former Prime Minister highlights how half the world’s population is threatened by malaria, which is entirely preventable. ‘We’ve known how to beat it for more than a century. Putting an end to malaria deaths would be one of the greatest humanitarian victories of the 21st century and it’s something really concrete that people of faith can work together on in very practical ways – both here in the UK by raising funds and awareness – and in those countries affected directly by the disease. ‘Funds raised for Malaria No More UK will go to save lives, with a focus on mosquito nets,’ adds Blair. ‘They cost just £5 and one net will save two lives and cover a mother and her child for up to five years. It’s exciting to see Premier backing such an important cause which has the potential to save many thousands of lives.’ Agencies, churches, organisations and individuals are working towards achieving the stated UN Millennium Development goals to ensure that every man, woman and child at risk of malaria has access to a lifesaving mosquito bed net by the end of 2010 and ultimately an end to malaria deaths by 2015. ‘Eliminating deaths from malaria would also have a reverberating impact on other aspects of global poverty and will help us achieve many of the other UN goals,’ insists Blair. When asked if he was concerned about the potential for western compassion fatigue at another appeal to help Africa, he was adamant. ‘No. There is as much reason to die from malaria as from a broken arm. Up until the 1930s-1940s the disease was rife in North America, Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal but we successfully controlled and eliminated it, and we can do the same in Africa. So, eliminating deaths from malaria by the UN target of 2015 is a goal within our reach. The potential to rid the world of the most devastating global health crisis of our time should be a great motivator for the UK public to act. ‘Moreover, I think that it is vital that governments and faith groups work together more on aid delivery. Faith communities play a huge role in service delivery in the developing world providing some 40% of healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa, with unparalleled authority within their local communities. Faith communities go beyond the tarmac - there are mosques, churches and temples even where there are no formal health centres to disseminate health messages and deliver services. Yet their potential is not being fully realised as they are underfunded and under-resourced – governments need to harness their power.’ Bishop Cleopas, the Anglican bishop of Matabeleland, which covers the western third of Zimbabwe, is a leader of a community of believers that government and aid agencies are using as educators and deliverers of aid in parts of Africa where corruption is rife and grassroots activists are thin on the ground. During a recent trip to the UK he told us how Zimbabwean Christians were making a difference: ‘The local church leadership make people aware, especially during the rainy season, that they should not let their children play near stagnant water,’ says Bishop Cleopas. ‘We explain that they should do their best to spray the stagnant waters, if they have the resources to destroy the eggs where mosquitoes breed. We also tell them that at night they must try to cover their children, either by using a light material to make a tent or a net. It depends on resources: if they have enough thin material to cover the entire bed to protect the children or to protect a sick person who may already be suffering from other diseases. ‘The church, like any other organisation in Zimbabwe, where the economy has been very bad, is really struggling to cater for those people who are likely to suffer from malaria, or to visit, educate or raise awareness. So we do what we can with the limited resources that we have. There are remote and rural areas of Matabeleland, where people have no access to drugs or mosquito nets. I’m so glad that a programme to provide nets is just starting in my diocese and that church members are involved.’ But the impact of malaria goes beyond the individual who is inflected. Bishop Cleopas highlights the economic consequences: ‘I don’t know the exact numbers of young people who suffer from malaria and never finish their courses, such as teacher training. Or people who are working and spend many months in hospital – it does take a long time to heal once you have malaria and are under treatment to recover. So there is a major impact on the economy as skilled people are unable to work.’ The Anglican diocese of Southwark is twinned with Matabeleland and a major focus of their work together is to raise awareness of malaria and how Christians in both Zimbabwe and the UK can partner to fight it. ‘We can all think and reflect about the huge death toll from malaria, but when you are working with real individuals that live under this threat, it has real impact,’ says Bishop Richard Cheetham of Southwark ‘It’s a link that we greatly treasure and we certainly gain as much from it as we give to it.’ Bishop Richard is committed to support the infrastructure of the church in Zimbabwe. ‘Bishop Cleopas has been doing a tremendous job. I believe that the church in Matabeleland is well placed to have a real effect if the resources can be channelled through them.’A combination of education and the provision of treated bed nets have made a big difference in Zambia and Ethiopia where rates of infection and deaths have been substantially reduced. The hope of Blair, Cleopas, and the 750,000 who are set to die this year, is that this message of hope will spread, and malaria will be conquered for good.

Case Study: Malaria - life and death

Deux-Anges’ mother and father do not make much more than $20 to $30 dollars per month selling small items such as soap or sugar along the sides of Goma’s roads in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Living in the poorest slum in the provincial capital, Ndoole Bamyere cannot afford for any of her four children to fall sick. So when Deux-Anges became weak with high fever, Ndoole waited until her temperature was dangerously high before bringing her to the local health centre. Malaria is the DRC’s most common killer disease. One in five children does not make it to their fifth birthday because of it. Five-year-old Deux-Anges is now sitting up in bed and beaming after she received a course of quinine by infusion – a treatment which cost her mother the family’s monthly income. ‘Many families cannot prevent malaria due to poverty,’ says a doctor at the centre, ‘then they put off coming for treatment as they cannot afford it. With severe cases, delaying treatment can be fatal,’ he adds. Close to a third of patients admitted to this health centre last month were suffering from malaria. Between January and March 2009, 300 children were treated for the potentially fatal disease. Malaria infections are treated through the use of antimalarial drugs, but the treatment is expensive. The liquid quinine and the consultation fees for the doctor will cost Deux-Anges’ family around $25. Other more effective treatments are usually too expensive for the average Congolese. Ndoole has only five dollars to pay the health centre today. ‘If I were to bring all the money now,’ she says, ‘we wouldn’t eat or save anything.’ The health centre allows her to pay in small instalments, as they did the last time Deux-Anges was sick. Her mother tells me she gets malaria often. This year she has been admitted for treatment three times. World Vision has been working with the health centre since the violence escalated in east DRC in October last year. As tens of thousands of displaced people fled towards Goma for safety, the city’s hospitals felt the full impact of the war. In response, World Vision provided medicines to four health centres and hospitals, allowing more than 10,000 war-affected people to receive free treatment. The number of people receiving lifesaving assistance in these centres tripled or even quadrupled, as those usually too poor to pay for medical care were able to access what was rightfully theirs. The agency also provided quinine, paracetemol to reduce fever, medication for rehydration and a drug which helps to prevent malaria in pregnant women. Now that these supplies have run out, poor families once again have to scrape together the little they have to buy essential medicines. Deux-Anges and her family need a sustainable solution to the high cost of medical treatment for the endemic disease. They need preventative and curative care they can access freely, without cost.As governments, aid agencies and campaigners consider fresh ways to tackle the disease, and assess progress towards global goals, poverty continues to mean families of children like Deux-Anges struggle to afford the most basic of care.

MALARIA – THE FACTS

How many people does malaria kill each year?

Globally malaria kills approximately 850,000 people every year – 85% of these deaths are in children under five. Other groups particularly at risk include elderly people, pregnant women and people suffering from HIV.How many people are infected by malaria each year?

There are almost 250 million cases of malaria worldwide each year. In the poorest countries malaria hits economic activity and diverts scarce household resources. Even one serious malaria infection can push a family into poverty due to the cost of care.How is malaria spread?

Malaria is an infectious disease transmitted by mosquitoes.What regions of the world are worst affected?

Sub-Saharan Africa bears the greatest burden of malaria, accounting for 90% of all global malaria deaths. The Worldmapper website has an interesting representation of the global distribution of malaria deaths. Despite reflecting total numbers from 2003, the geographical distribution of malaria remains much the same to date: Visit WorldMapper