I’m a planner. I book everything ahead – phone calls with friends, days out, dinner plans.

You see, I like to feel in control, and I was under the impression that by planning for the future, I could make it predictable, safe and familiar.

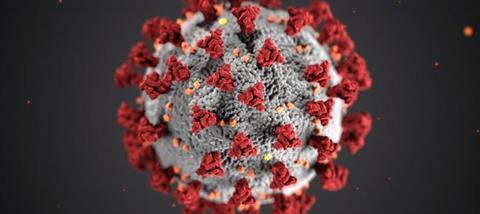

This Lent, the time in the church year when we make ourselves vulnerable to learning what we are really trusting instead of God, that sense of mastery has been ripped from my fingers. Not, I’m afraid to say, by any spiritual discipline that I intentionally adopted, but by Covid-19, the pandemic that has turned our world upside down.

I don’t think I am alone in catching sight of parts of myself I would rather not see in the mirror that this crisis is holding up to our society, showing us who we are and what we value like nothing else has in living memory. It feels like the whole world for once has the same concerns, the same word on its lips.

It’s not just our addiction to control and the fact that we have been privileged enough to think we could enjoy a perpetually stable existence which vast swathes of the world’s population lack. The empty supermarket shelves reveal the destructiveness of our impulse to self-preservation at the expense of the common good and how fear drives out love.

The anxiety we feel in the face of so much time spent indoors shows how much we have relied on busyness and entertainment to distract us from ourselves. Even if those around us wouldn’t put it like this, we are all wrestling with our idols en masse – the things we hope will give us peace, contentment, and security but which ultimately, inevitably let us down.

But we are also learning more about what it is to be human. Workers who were previously overlooked, like delivery drivers, are now recognised as utterly indispensable. I never used to give a second thought to the supply chains on which I rely to keep myself fed, healthy and clean; now I think of little else.

And as we see the ripple effects from particular parts of society shutting down, like our schools, it is hard to escape the fact that John Donne had it right when he wrote “No man [sic] is an island, entire of it self; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main”. I studied that four-century-old poem when I was at school and nodded in agreement, but I don’t think I really knew in my bones what it meant until now. Our interconnectedness and our interdependence has never been so glaringly obvious.

And we are also, thankfully, seeing the best side of human nature – compassion, creativity, generosity and ingenuity. Community groups have sprung up out of nowhere to care for the vulnerable and isolated; thousands of designers and engineers have started working together online to create open-source emergency medical supplies; and many businesses are offering their goods and services for free to the NHS workers we need even more than ever.

I once had cripplingly large ambitions of changing the world single-handedly, a second messiah complex if you will. But now I appreciate how much a difference can be made just by offering up whatever you have - time, gifts, money - when a need arises.

And so, we are faced with a Lenten opportunity like no other: a revealing exposé of our darkest side, a portrait of who we were made to be, and a light at the end of the tunnel which all the pain, and all the suffering, and all the evil in the world will never vanquish. (That light, by the way, knew that we were really like this even when we were blissfully ignorant, he saw the stockpiling and the judgmental assumptions we would make of one another and he loved us anyway.)

Of course, any experience of suffering has the potential to make us more like Jesus. As Paul encouraged the Romans, it produces endurance, character and thence hope (Romans 5:3-4). In that respect at least, Covid-19 is not unique.

But this self-reckoning is happening simultaneously and on a global scale. The opportunity for deep and lasting change is, therefore, even more real. Transformation is just as contagious as fear. That is, after all, what it means to be salt and light: by the Spirit of God, tiny sprinklings and scatterings can change the whole substance irrevocably.

When our whole society is geared up around individual satisfaction, instant gratification and consumerism, it is hard to hold loosely onto the things of the world like Jesus did. So, with all of that stripped down, the emperor so publicly exposed (can anyone believe that the things we were worried about last month occupied a single ounce of our brain-space?), perhaps the kingdom of heaven is closer than we dare imagine.

Covid-19 may have turned our world upside down, but maybe it was the wrong way up in the first place. Maybe we all have the chance, by the grace of God, to reorient it right again.

Florence Gildea is a writer based in London. Her debut book Lessons I Have Unlearned: Because Life Doesn't Look Like It Did In The Pictures will be published in 2021

Premier Christianity is committed to publishing a variety of opinion pieces from across the UK Church. The views expressed on our blog do not necessarily represent those of the publisher.