Theologians from the UK’s top Bible colleges talk to Sam Hailes about migration, revival, formation and keeping it weird

Where do ideas come from?

It’s commonly thought that many ideas begin with intellectuals in the academy dreaming them up, before they ‘trickle down’ into popular culture. For example, long before the word ‘woke’ was used either by campaigners in support of racial justice or, more recently, as an insult on the internet, the complicated concepts around it (postmodernism, critical theory, political philosophy) were being debated in prestigious universities. Over time, some of these concepts trickled down.

If one applies this principle to a church context, it could mean the profound point you heard communicated in a Sunday morning sermon may have originated in a dense book written by one of Church history’s greatest minds. But, over time, the insight has filtered down and been recommunicated in a way that everyday people in the pews can understand.

According to Chris Howles, director of cross-cultural training at Oak Hill (oakhill.ac.uk), this can also happen in reverse, and ideas can filter up: “Sometimes the academy can be behind local churches when it comes to what’s happening.”

In recent weeks I’ve been speaking to a range of experts about the most significant new ideas that are either filtering down or filtering up, and influencing the way Christians think and live in the world today. Here’s what I’ve discovered.

1. Christians are migrating

There are more people on the move around the world today than at any other point in history. By 2050, 1.2 billion people could be living outside the country of their birth, according to UN figures.

Howles references an “astonishing stat” he heard from Malawian theologian Dr Harvey Kwiyani that while just 14 per cent of Londoners are Black, they make up 60 per cent of people in our capital’s churches on any given Sunday. This is evidence, says Howles, of how African heritage immigration is “revitalising and reenergising” Christianity.

But it isn’t just London. Most churches in the UK are thought to be multicultural, meaning Christians are being forced to grapple with new questions that previous generations never needed to ask. As Howles puts it: “What does it mean that I’m worshipping alongside people who come from different places and, therefore, wonderfully and inevitably have different perspectives on the scriptures, God’s character and the nature and form of worship, ministry and mission?”

Christians are more migratory than any other religion

Of course, this topic can quickly become political and divisive, especially as debates around immigration dominate headlines in the UK. While he’s broadly positive about immigration, Howles acknowledges the speed of cultural change has been “unsettling” and “disruptive” for some. “I would quite genuinely sympathise with that,” he adds.

The implications for mission are stark. Gone are the days when the view of Christian mission was “from the West to the rest”, says Howles. Instead, the faith is polycentric (meaning: to have more than one centre). “Power is much more distributed and scattered than it was a generation ago.” But with demographic trends pointing to an increased “domination” of Africans in world Christianity, Howles wonders what the implications might be for the Church’s life and theology. (See point 4 for one potential answer.)

The extent of migration around the world today may be unprecedented, but according to Howles, it is no accident. “God has purposes in migration,” he says, pointing out that the idea goes all the way back to Genesis 3 when Adam and Eve were expelled from Eden. He also summarises Stephen’s speech in Acts 7 as: “God, through the Old Testament narrative, isn’t restricted to one particular territory or even people or culture or setting. And therefore, God, fundamentally, is a God on the move.”

Howles adds that in contrast to other belief systems, which tend to remain dominant in one or two geographical areas (Hinduism in India, Islam in Asia and the Middle East), Christianity is genuinely worldwide.

“Christians are more migratory than any other religion. There’s something inherently God-given about being people on the move because we have a God who cannot be trapped in a particular place.”

“Yes, God came down in a particular place. But look at Pentecost, with a view to all peoples, all languages, knowing and hearing the gospel of Christ. It’s ultimately a universal faith; a translatable faith.”

Want to go deeper? Read Lessons from the East: Finding the future of Western Christianity in the global Church by Bob Roberts Jr (David C Cook)

2 A religious renaissance?

This trend has been given various names, the most recent being “vibe shift”. Others talk about a “religious renaissance” or maybe even revival. The former editor of this magazine, Justin Brierley, was probably one of the first to identify the trend when he dubbed it: “the surprising rebirth of belief in God”.

Brierley’s book and podcast of the same name make the case that the New Atheism era, best exemplified by Richard Dawkins’ runaway 2006 bestseller The God Delusion (Bantam Press), has fizzled out and come to nought. The cultural trend is now towards faith in God, rather than away from it. Brierley cites high-profile intellectuals who are now taking Christianity seriously, with some former new atheists – such as Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Dawkins’ former right hand man Josh Timonen converting. After years of equivocating, the popular Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson recently affirmed “Jesus is God” during an interview on Steven Bartlett’s ‘Diary of a CEO’ podcast. Meanwhile, the historian Tom Holland’s widely influential book Dominion (Abacus) powerfully makes the case that much of what we consider Western morality or values is, in reality, deeply Christian.

The cultural trend is now towards faith in God, rather than away from it

The principal of Moorlands College (moorlands.ac.uk), Andy Du Feu, supports the theory that there’s a new openness to faith in the UK. “We’ve got an open goal for Christianity in our culture,” he tells me.

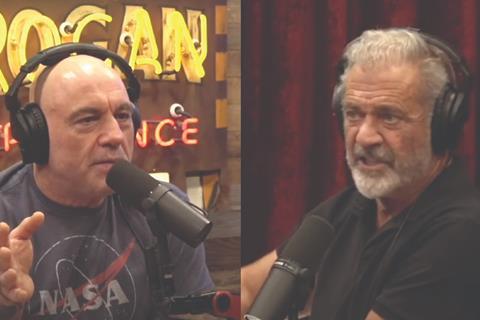

The landscape looks completely different to the early noughties when Alastair Campbell famously quipped: “We don’t do God!” and Christianity was caricatured in the Vicar of Dibley, says Du Feu. He cites Joe Rogan, the biggest podcaster in the world, who just invited the Christian apologist Wesley Huff onto his show for a three-hour back and forth about the authenticity of the New Testament. The YouTube video alone has had 5 million views so far. “Rogan is engaging his massive following with Christian ideas in a way he wouldn’t have touched five years ago,” says Du Feu. “He would have scoffed and mocked them.”

While Du Feu is convinced a “religious renaissance” is taking place, he admits that there’s some work to be done in moving people from a general curiousness about spiritual matters (he cites popular YouTube videos where claims abound that UFOs are demonic) to “a saving faith”.

Looking to the future, he even wonders if the year 2033 could mark a peak or apex. “Granted, Jesus was probably born 4 BC but, notionally, this date is a key moment. The next eight years could be a powerful moment for us in our culture, if we take it as a Church.”

Want to go deeper? See Justin Brierley’s The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God book and podcast series

3 The growth of spiritual formation

There has been an explosion of interest in spiritual disciplines, practices and habits among Christians in recent years. Whether it’s the new monasticism of 24-7 Prayer (and their popular ‘Lectio 365’ app) or the works of US pastor John Mark Comer (see his lockdown phenomenon The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry [Hodder & Stoughton]), many Christians are exploring and rediscovering ways of slowing down and reconnecting with God. This might mean instituting a weekly Sabbath, taking up the habit of fasting regularly or being more generous with your money. For others, it’s a recommitment to the daily practice of scripture reading.

It’s hard to deny the Bible speaks very explicitly about spirits, angels and principalities

What is driving this trend? Some posit a string of scandals involving high-profile Church leaders have prompted Christians – both leaders and lay people – to get back to basics and ensure they are actually living out the Christian message in practice. Others wonder if churches which preached a message of grace (God loves you the same even if you never pray or read the Bible) failed to balance this with adequate teaching on why you should nevertheless put time aside to be with God.

In her recent book Fully Alive (Hodder & Stoughton), the writer and broadcaster Elizabeth Oldfield gives another explanation. Like many evangelicals, she grew up viewing set prayers and texts as “dull and rote”.

“I spent a long season thinking only entirely spontaneous, ‘authentic’ self-expression counted, including in prayer, and that all tradition and structure was deadening.

“However, as I age I begin to see the value of regular (even, whisper it, sometimes mindless) repetition. Some days the words come alive and feel deeply sincere, my thinking is stretched and enriched by their beauty, and other days I say them out of habit, but they are always forming me.”

While rediscovering ancient liturgy or developing new prayer habits is to be welcomed, Du Feu thinks there are potential dangers, too. He’s noticed a “surprisingly legalistic worldview” even around good disciplines such as Bible reading. He cites the example of one student who was engaged in a reading plan on the YouVersion Bible app. The app had logged the number of days the student had read the Bible consecutively (known as a streak).

“This student said: ‘Andy, I need to confess to someone. I missed a day. I woke up at 6am and realised that I’d missed my streak. So, I put my clock back on my phone to the previous day, did the devotional, and then carried on.’”

Du Feu’s analysis is that for this student, gamification (adding elements of game playing such as point scoring to encourage greater engagement within an app) has gone from a blessing to a curse. Racking up a lengthy streak of daily Bible reading was no longer a positive incentive to engage with God, but “a legalistic tool”.

Another concern comes from Carey Nieuwhof, a US blogger on Christian leadership. He fears that ‘discipleship’ has become a buzzword in the Church, and now “everyone is focused on it”. While at pains to point out that he believes discipleship is vital, there is a risk that Christians could focus on it too much, turning inwards and forgetting about evangelism. Carey’s suggestion is that while spiritual disciplines are important for individual growth, the Church must not lose sight of the mission field and a world in need. A thriving devotional life should never come at the expense of ignoring the great commission.

Want to go deeper? Try the Practising the Way course from John Mark Comer (practicingtheway.org/resources)

4 Embrace the weirdness of faith

It isn’t clear what caused it. Perhaps it was the aggression of the new atheists, our post-enlightenment culture or a misguided quest for cultural relevancy among some Christians. But, at some point, a significant part of the UK Church stopped talking about the supernatural. We became embarrassed by it.

So much so that even those on the fringes of faith noticed it. Holland once told a group of Christian leaders: “You need to talk more about the weird stuff.” Unpacking this further in a conversation with the evangelist Glen Scrivener, Holland explained: “I see no point in bishops or preachers or Christian evangelists just recycling the kind of stuff you can get from any soft, left liberal, because everyone is giving that. If I want that, I’ll get it from a Liberal Democrat councillor. If you’re a Christian, you think that the entire fabric of the cosmos was ruptured by this strange singularity when someone who was God and man set everything on its head. To say its ‘supernatural’ is to downplay it!”

Christians may be tempted to think minimising the strange parts of faith will help the Church be culturally relevant, but it seems the opposite is true. According to surveys, most people in the UK believe in angels. Statistics also show a rise of interest in astrology and occult practices. Talking more about the supernatural could be an effective evangelistic strategy.

With this in mind, Emmaus Rd church in Guildford launched a sermon series entitled: ‘We do weird’ last autumn. It covered topics including prophecy, signs and wonders and spiritual warfare. Introducing the series, their senior pastor, Pete Greig said: “Most of the people you’ll meet this week believe there’s more to life than this life.

“Cynical secular humanism that seemed so certain is starting to shake and to shatter. Belief in the supernatural is fully back.” He invited listeners to “question the craziness of an exclusively materialistic, entirely godless worldview” and replace it with “an infinitely more credible, increasingly more plausible and attractive conviction that our world is in fact enchanted…fizzing perpetually with supernatural impossibilities”.

Howles agrees. “It’s very hard to deny that the Bible speaks very intentionally and deliberately and explicitly about a universe that is inhabited by this middle realm of spirits, angels and principalities and powers.” Christians from the majority world who migrate to the UK are helping the Church to rediscover parts of the faith that white Brits have become “uncomfortable with”, he adds.

“African and Asian Christians, who haven’t necessarily inherited this kind of Enlightenment-shaped dualism between the natural and the spiritual, often have a more holistic worldview where those two things are integrated.

“[They] often recognise how the spiritual and the physical interact and so are willing to recognise that there are some things that need to be explained by the presence of angels or demons or principalities and powers. Many of us Westerners can sometimes feel quite uncomfortable thinking in those terms.”

Want to go deeper? Watch Darren Wilson’s documentaries, including Finger of God, Furious Love and Holy Ghost which feature miraculous stories of God at work around the world today (wpfilm.com)

No comments yet