The best decision anyone can ever make, at any point in life, in any circumstances, whoever they are, is to become a disciple of Jesus Christ. There is no better decision for any human being in this life.

Karl Barth, one of the greatest theologians of the 20th century, said, ‘No other task is so urgent as that of spreading the news on earth and making it known.’

Our country will not know of the revolutionary love of Christ by Church structures or clergy, but by the witness of every single Christian.

THE CALLING OF SAINT MATTHEW

The Calling of Saint Matthew was painted by Caravaggio around 1599. Art historian Sir Kenneth Clark considered it the piece of art that changed the history of painting.

The painting is a representation of the scene in Matthew 9 when Jesus calls a tax collector to follow him. It shows Matthew, the tax collector, in the centre of the image, surrounded by four colleagues.

The finery of those around the table contrasts with Jesus’ and Peter’s clothing and bare feet. Two of the tax collectors, at the far left of the picture, do not even look up, so intent are they on counting their money.

There is a barrier of darkness between the five men and Jesus. All the light has come in with Jesus – the figure on the far right of the picture. Jesus is the source of light; it doesn’t come from the window, in which we see the cross.

Evangelism is the good news of the coming of Jesus Christ into this dark world. Without this light, we are in the dark. The light comes to us unwarranted, unsought, without our initiation. This is the free work of God to bring light into the darkness. It’s not technique, manipulation, organisation or systems. It is God.

The men in the picture were not looking for Jesus; he came to them and transformed their world. In fact, he caused great disruption. Apart from him there is only darkness. Jesus is the light of every person; he comes to all and for all. He comes not just to those who might seek him.

JESUS REACHES OUT

Caravaggio brings drama into this painting through the outstretched hand of Jesus. His hand singles Matthew out. It’s a definite choosing – a particular invitation. In the same way, Jesus comes and reaches out to each of us.

Those who first saw the painting could be in no doubt as to what Caravaggio was implying – notice the similarity between the hand of Jesus and the hands in his scene from the roof of the Sistine Chapel. The hand of Jesus is both the hand of the second true Adam and of God.

The gospel is the call of God through the true man, Jesus Christ. It is an act of creation, and recreation; a bringing into being, a life-giving calling, which is only possible because of the initiative of God. We do not bring about this alteration, but it has been accomplished in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

We did not contribute to it, but we are alive because of it. As we get hold of that truth, we are impelled outwards into the world. Because it’s as that truth grabs us that we remember that this isn’t us, it’s God.

WHO…ME?

Matthew clearly can’t quite believe that this invitation and command are addressed to him. Surely there has been some mistake?

You can see him thinking, ‘Me? What, me? You’re kidding. Wrong guy. There’s another Matthew down the road.’ What could he have done to have warranted this action of God?

Pope Francis said: ‘That finger of Jesus, pointing at Matthew. That’s me. I feel like him, like Matthew. It is the gesture of Matthew that strikes me: he holds on to his money as if to say, “No, not me! No, this money is mine.” Here, this is me, a sinner on whom the Lord has turned his gaze.’

Does that ring bells with you? That beautiful, wonderful moment when you realise that Jesus looks on you, and doesn’t hate, doesn’t despise, is not indifferent, but utterly compelled and compelling in love. He says, ‘Follow me.’

As a Christian, it is my deepest conviction that in Jesus Christ, God comes to call every one he has made. Everyone has been summoned in Jesus Christ. For in Jesus Christ, God has poured out his love and his grace, his forgiveness and his mercy, his faithfulness. God would not be doing this without you or me.

Evangelism is, then, a joyful proclamation of what has happened. It’s the news of Jesus Christ. His life as the light breaking into this dark world for us. His death as the fount of our redemption. His resurrection as the hope of all. This news must be told, or how will people know?

GRACE

‘Grace’ is the most beautiful word in the English language. The gospel comes to me as a sinner and astounds me with the news that I am loved, accepted, forgiven, redeemed and chosen in Jesus Christ.

My spiritual director visited me recently. He’s an extraordinary Swiss monk and he celebrated mass in the Crypt Chapel inside Lambeth Palace. It was a wonderful moment when those among us who are not Catholics received a blessing, and the Catholics received the eucharist – the opposite to what has been the normal pattern at Lambeth. And we felt that pain of the Church’s separation.

GRACE IS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL WORD IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

He said: ‘We can do nothing except by grace.’ It’s his great phrase: ‘C’est tout grâce.’ It is all grace.

We must open ourselves and the Church to the continual conversion which the spirit works in us. The Church must continually be converted from the reduction of the gospel into its fullness.

We cannot leave things as they are, but we experience grace best by bowing before it and allowing it, every time, to begin with us as though it were for the first time. Each day the gospel comes afresh to me and astounds me with the news that I am loved, accepted, forgiven, redeemed and chosen in Jesus.

And if every Christian knew only to receive his grace afresh each day, what transformation would there be?

WHAT COMPELS US?

The motive that drives evangelism is never that numbers are looking low and the future of the Church is looking bleak. This is not a survival strategy; evangelism is not a growth strategy. Of course we want to see full churches. But this is not about self-survival.

Martin Luther defined sin as a heart curved in on itself. The Church which is concerned primarily for its own life or survival, a church that is curved in on itself, is signing its own death warrant.

The wonderful missiologist Lesslie Newbigin once said: ‘A church that exists only for itself and its own enlargement is a witness against the gospel.’ Both a lack of action and too much frantic action thinly mask a lack of confidence in the sufficiency of God.

What compels this priority of evangelism is the same motive that compelled the first proclaimers; that compelled Archbishop William Temple’s great report in 1945, ‘Towards the conversion of England’; that compelled evangelist Billy Graham, and that compelled the decade of evangelism.

2 Corinthians 5:14 says it is the love of Christ that compels us. Often I have failed to act in the love of Christ, and because of this, there has been little response.

Sharing the good news is not easy or without cost for any of us. The Greek word for ‘witness’ is ‘martyr’. We are more and more, in these days, confronted with the fact that the word has come to have associations with death, because of the price the first witnesses were prepared to pay to be faithful.

Recently, 21 Christians were murdered in Libya. I was talking to Bishop Angaelos, the Coptic Bishop in England, who I went to see to offer condolence. He told me that from one who escaped, they heard that as each one was killed, most savagely, they cried out, ‘Jesus Christ is Lord.’ Their final words were words of witness.

Finally, returning to Caravaggio’s painting, down at the bottom of the picture, there is another hand that mirrors the calling hand of Jesus. It’s that of Peter. You see him hesitant, not confident, and seeming to look not at Matthew but one of his friends.

Jesus involves us in his work of calling people to follow him. This is the work of evangelism.

Like Peter, however weakly, however hesitantly, he calls us to extend our hands and our hearts, to use our words and lives, to echo his call to every person to follow him.

For the best decision anyone can ever make is to be a follower of Jesus Christ.

Adapted from the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Lambeth lecture, Revolutionary Love. Watch in full at premier.org.uk/welby.

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas Caravaggio (c.1601–02)

This depicts Thomas touching the wound in Jesus’ side. Art writer Louella Esguerra says, ‘This painting contains several lessons for the viewer. It teaches the loving nature of Christ to unbelievers. It illustrates the fellowship and intimacy of believers with God and each other. It demonstrates the truthful nature of Christ, ending the lesson with a rebuke to unbelieving hearts. And it is a lesson on faith, essential to the Christian, as it is impossible to please God without it.

The Light of the World William Holman Hunt (1851–53)

This allegorical painting illustrates Revelation 3:20: ‘Behold, I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and eat with him, and he with me’ (ESV UK). Hunt said it was through working on the painting that he became a Christian. He painted three versions of The Light of the World, the largest of which is situated in St Paul’s Cathedral. The painting has been exhibited across the globe and seen by millions.

The Return of the Prodigal Son Rembrandt (c.1669)

This oil painting depicts the moment the prodigal son returns to his father. Rembrandt scholar Rosenberg calls the painting ‘monumental’, writing that Rembrandt ‘interprets the Christian idea of mercy with extraordinary solemnity, as though this were his spiritual testament to the world’. Dutch priest Henri Nouwen (1932–96) was so taken by the painting that he wrote a short book about Jesus’ parable, using Rembrandt’s painting as a framework.

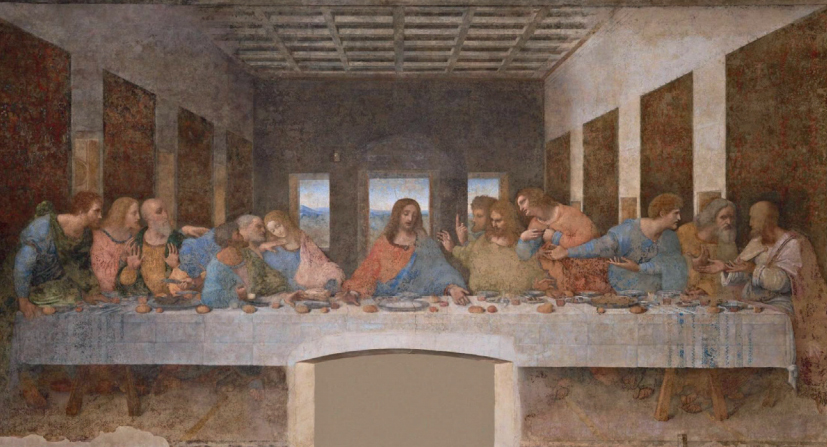

The Last Supper Leonardo da Vinci (1495–98)

Leonardo da Vinci painted The Last Supper on the back wall of the dining hall of the Dominican convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The painting contains a number of allusions to the number three, (perhaps symbolising the Trinity). The disciples are seated in groups of three and there are three windows. The figure of Jesus is given a triangular shape, marked by his head and two outstretched arms. Even before the mural was complete, it suffered from damage as paint began to flake off the wall. Numerous restoration attempts have been made.