When is a loaf not a loaf? No, it’s not a Christmas cracker riddle. This question was a matter of serious debate among rabbis in Jesus’ time. They were worried about tithing bread that was inedible. At what point was it so stale and mouldy that it didn’t have to be tithed? In the end they decided a baker had to count any loaf that would be eaten by a shepherd; that is, someone of the lowest social standing.

THE SHEPHERDS AND WISE MEN: SCUMBAGS AND DODGY FOREIGNERS

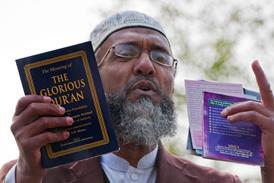

So why were shepherds the best Luke could scrape together for his record of those giving an earthly welcome to the newborn Messiah? Matthew fared even worse. He had to resort to admitting that gentile astrologers – people who were despised by every pious Jew – were in attendance.

If we displayed a nativity scene in a realistic modern setting it would look very different from the cute tableau to which we have grown accustomed. Today, Jesus’ visitors would be homeless drug addicts and rich drug barons; the poorest and richest of the despised. It wasn’t that the Gospel writers were making a theological point. They were simply making the best of the facts. They had to deal with the uncomfortable truth that Jesus was a nobody except to those who could see behind the grime.

THE HOLY FAMILY: SKINT, SCARED AND ON THE RUN

The blue robes we see on proud, pint-sized nativity play Marys are nice but unrealistic. Mary and Joseph would have looked like peasants fending off animals that were trying to get at the feeding trough occupied by their baby. Perhaps Jesus was quiet, as ‘Away in a Manger’ claims, but if he was it would only have been because he was tightly constricted by swaddling rags. This stops babies crying but is more comforting for the parents than for the children, whose muscle development can be restricted if the swaddling is applied for hours on end. You’d think God would have picked a better situation for his son’s incarnation!

But Jesus had to arrive ‘under the radar’, as they say. Herod had already murdered various relatives who might have been rivals for the throne. The story of him killing the babies and toddlers after Jesus’ birth (Matthew 2:16) doesn’t surprise modern historians and wouldn’t have warranted a mention from ancient historians.

The wailing Herod caused that night was nothing compared with his plans for what would follow when he died himself. He had all the best-loved leaders of the nation imprisoned, ready to be executed as soon as he passed away. His plan (which the jailors refused to carry out once he was gone) was that the nation would at least have something to mourn on the day of his death.

After Jesus’ birth, things got worse as the family became foreign refugees in Egypt. Modern refugees queuing for water in UN camps are much better off in comparison. Mary and Joseph were being hunted by the most powerful monarch in the region, and he knew their family identity. So, like criminals on the run, they had to avoid all contact with officials until Herod was dead. And then, when they returned home, the real persecution started.

JESUS: THE ILLEGITIMATE CHILD WITH A BACKGROUND

Not long ago, I was banned from ever addressing the local Cubs and Scouts again because of my Christmas talk. I asked them which of the following was not a real or historical person: Jesus Christ or Father Christmas. All the kids put up their hands for Santa…and their parents were horrified. Their little darlings knew the truth!

Matthew and Luke weren’t hiding the truth, but they did want to distract their readers from the real problem about Jesus’ birth: the sordid assumption that Jesus was a mamzer (Hebrew for ‘bastard’). Those in Nazareth knew when Jesus was due and when his parents had married…and they could count.

News like that spreads quickly. John’s only mention of Jesus’ birth comes from a heckler: ‘Where’s your father?...At least we weren’t born in fornication’ (John 8:19,41, KJV). Jesus, an expert public speaker, was used to such insults and quickly turned it around, by answering (in summary): ‘My Father is in heaven, but you can’t rely on Abraham as your father’ (vs19-40). This kind of thing must have happened depressingly often, because his unmarried status made people wonder about him. No pious Jew at the time refused to obey the first command in scripture: be fruitful and multiply (Genesis 1:28), unless they simply couldn’t.

If a man wasn’t married by his mid-twenties, everyone assumed the worst about his legitimacy and he was stigmatised (for example, they weren’t allowed to teach boys unaccompanied or even look after animals on their own). But even a mamzer could get married, provided it was to another mamzer.

Yet Jesus was different. He was an ‘unofficial’ mamzer because no one could prove it. So he couldn’t marry a mamzer, and no good Jew would let him marry his daughter. His singleness stood out as an accusation that demanded an explanation.

THE VIRGIN MARY: THE BIZARRE CLAIMS OF A ‘FALLEN WOMAN’

The first century was a sceptical age, when miracles were viewed as part of the glorious past. Any new miracles were assumed to be the work of the devil or of charlatans, so the Gospel writers were probably apprehensive about recording Jesus’ miracles. They knew they had to present them positively because, if they didn’t, detractors could say: ‘Yes, but wasn’t Jesus that religious nut who claimed to heal people?’ Contrary to what we might expect, his miracles weren’t something they wanted to publicise.

IT STOOD OUT LIKE A PINK DRESS AT A FUNERAL: JESUS WAS BORN OF MARY, BUT NOT JOSEPH

The early Church fathers got round this ‘problem’ by highlighting Jesus’ wisdom instead of his miracles. In later centuries his miracles became central again when people were less sceptical about the supernatural. Therefore, in the anti-miracle climate of the first century, Mary’s story about a virgin birth was laughable at best and blasphemous at worst.

Mary could have said that she had been raped by a Roman soldier or that Joseph couldn’t wait. She wouldn’t have attracted nearly as much scepticism and pious horror by doing so, and many people would have been sympathetic; in private, at least. When she fell pregnant, Mary didn’t go to stay with a young, irreligious branch of the family. She went to an elderly, pious, priestly couple, from whom she could expect to find the least understanding. She would never have done this unless she had thought they would believe her.

Mary’s extraordinary behaviour and her unconvincing story create a problem for the historian who has to choose between two unlikely scenarios: that either she deliberately made up a story that would ruin her life or that she actually believed it. Like us, the Gospel writers are trying to convey the tale in as believable and presentable a way as possible, cleaning it up by downplaying the scandalous elements. We, of course, neaten it even further by turning it into the ‘nice’ story that children act out in school nativity plays.

THE INCARNATION: GOD BECAME ‘FLEISCH’

Mark appears to say nothing about Jesus’ suspect birth, but for Jewish readers his account is the most damning of all because he refers to ‘Jesus, son of Mary’. Using a mother’s name like this is unparalleled in ancient Jewish literature. Surnames always came from the father’s name, such as ‘James bar Alphaeus’ or ‘Simon bar Jonah’ (‘bar’ is Aramaic for ‘son of’). In the same passage, Mark lists all of Jesus’ family except his father (Mark 6:3). This isn’t because Joseph was dead; that would have made it even more important for his name to be remembered through his sons. It was because Jesus wasn’t his son.

Matthew is similarly shocking – though, again, modern readers wouldn’t notice it – when he suddenly ends his genealogy with a female pronoun. A long series of ‘and he begat…and he begat’ ends with: ‘…Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born’ (Matthew 1:16, ESV). This doesn’t look strange to us, but the ‘of whom’ is feminine, and for contemporary readers it stood out like a pink dress at a funeral: Jesus was born of Mary, but not Joseph.

In contrast, John presents a majestic beginning for Jesus, but he only keeps it up for a few verses. I didn’t notice this until a few years ago when I tried to translate John’s prologue in Luther’s German Bible using Google Translate. When it got to verse 14, the translation was: ‘And the Word was made meat, and dwelt among us.’ Of course the German word fleisch means human ‘flesh’ as well as butcher’s ‘meat’. But then it hit me. That is exactly what the Greek implies: God became meat! Our old English ‘flesh’ has become a theological word, but it still means ‘meat’.

Imagine going to live in an ant farm as an ant. Jesus lowered himself much further than that when he became human. Now imagine being born there, as something smaller than a grub, inside a cell at the honeycomb-like centre of the colony. And now imagine being fed by a worker ant who regurgitates food for you from his gut. It’s an analogy that may help us go some way towards understanding the incarnation. Human birth and bodily functions can’t have seemed very appealing when viewed from heavenly glory. God became meat for us, and at a time when there was little hygiene and few home comforts, and when daily life was hard and often disgusting.

SCANDALS THAT HAVE A RING OF TRUTH

I prefer the dirty and messy facts about Christmas to the more sanitised versions because they have a ring of truth about them. Given the choice, no supporter of Jesus would have fabricated the dodgy visitors, an ignominious birth and background, or his mother’s bizarre claim of a virgin conception. It was a problem from the start and it still is. It conveys the opposite of glorious birth accounts in mythology and fairy stories.

To the first generation of readers it didn’t proclaim the majesty of Jesus’ birth. Reading between the lines, they could see that Jesus’ origins were beneath even the lowest echelons of respectable society, and the stories surrounding it appeared as lazy lies designed to cover up a scandal.

Today, however, the Christmas scandals in the Gospels are like gold dust to historians because they know that no one would make them up. In the dust of uncertainty they shine out like diamonds; as facts that can be relied on.

There is absolutely no doubt that Jesus’ birth was strange: strangely horrific, strangely wonderful, or perhaps a combination of both. But there’s one thing it definitely wasn’t: it was never ‘just a nice story’.