You might be surprised to know that the word ‘gospel’ was first used to describe the Roman Caesar Augustus, not Jesus. But how should Christians interpret it today for our post-Christian culture?

Followers of Jesus may know what the gospel of Jesus is and that, as a Christian, you’re supposed to share it. But you may be surprised to know that the word “gospel” wasn’t always a Christian term.

Before it became synonymous with Christ and his kingdom, it was about Caesar and Rome. And the story of what it meant, and what it’s come to mean, impacts our witness today.

The Gospel of Caesar

Ten years before Jesus was born, an ancient city installed an inscription honouring the birthday of the Roman Emperor, Caesar Augustus. Scholars call it the Priene Calendar Inscription. You might recognise the language: it contains the phrase “the beginning of the gospel for the world” and goes on to list the many accomplishments of Caesar. The fact that this “gospel” (definition: good news) was connected to Caesar’s birthday isn’t a coincidence.

For the Romans, time itself was organised by Caesar; it was a sign of his power. Caesar Augustus still impacts our calendar, every month of August. The Emperor organised history like this, but Romans held that he also interpreted it.

We cannot confuse the collapse of cultural Christianity with the defeat of the gospel of Jesus Christ

Caesar gave history itself meaning and purpose for Rome. When ancient Romans passed by this inscription in their town square, they knew the “gospel of Caesar Augustus” was the announcement of a new era; a new kingdom with a fresh peace, justice and promise of security.

This was the world of Jesus of Nazareth, who was born in a backwater Roman province about a decade after this inscription was installed. After Jesus’ execution and resurrection, the first Christians searched for words to explain his significance. It perhaps shouldn’t surprise us that the word they latched onto was “gospel”.

A different gospel

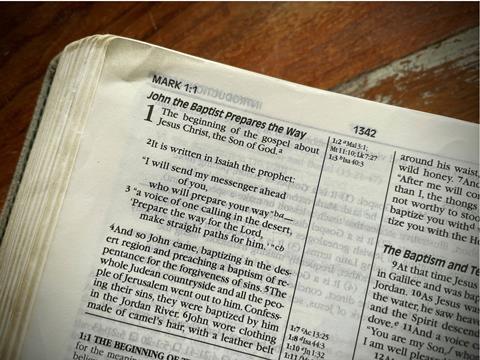

Mark opens his written testimony of Jesus’ life with the line: “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” This wasn’t Mark just pulling words out of thin air; it was a direct challenge to Caesar’s power and place at the centre of history.

The gospel of Jesus’ kingdom constitutes a different centre of history. The scandal of this kingdom was its inauguration by an instrument of Roman power, the cross. The cross was supposed to weaken threats to Rome and silence Roman criminals. Instead, it became the power of God, bringing forgiveness, justice and mercy to all.

When the early Christians used “gospel” to describe the significance of Jesus, they knew it forced a decision. Their choice of words provoked a choice of will for their Roman neighbour: What will you make of this Jesus?

When we understand the cultural origins of “gospel” we can wrestle with the truly radical nature of the message of Jesus Christ for us today. We can imagine not only what it means in our present moment, but also what it means for it.

The gospel in a post-Christian culture

The West is becoming “post-Christian”. This doesn’t mean it’s less religious and more atheistic. Instead, I am drawn to Most Rev Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury’s analogy. He imagines post-Christian societies as a landscape littered with the shattered remnants of cultural Christianity. He says politicians today pick up these shards (like “gospel”) to wield against their opponents. Others use these shards as shibboleths, rallying support to their causes. But these shards lack the common story, which bound them together and gave them meaning. They are less interpreted by the language of theology and more by political expediency or cultural utility.

Everyday people are all affected by this post-Christian moment. Think of your colleague who says something like: “That’s the gospel truth!” You instinctively know they don’t mean anything particularly Christian by that phrase. Or we might hear “gospel” and think of the injustice of colonialism, equating ‘salvation’ with ‘civilisation’. There’s a positive legacy too. Glen Scrivener and Tom Holland point out our modern belief in things like human rights or equality are thanks to Christianity. And they are right. It’s all a mixed bag.

Which is why, in a post-Christian culture, words like gospel or sin aren’t commonly used by people to explain or interpret their everyday lives. They’ve suffered overuse or misuse, and have become cultural refuse.

The gospel for a post-Christian culture

Some condemn post-Christian society for rejecting the gospel. But we ought to be imagining our responsibility to post-Christian society. In the larger collapse of cultural Christianity, the overuse and misuse of words like gospel has created a new moment with novel conditions for the Church. But these new conditions sometimes make nostalgia an attractive option.

Mark wasn’t just pulling words out of thin air; it was a direct challenge to Caesar’s power and place at the centre of history

The gospel for a post-Christian culture is not one which attempts to make up for cultural loss through political control. For Jesus, what mattered was gathering the lost sheep, the lost coin, the buried treasure. Maybe we should do the same.

The Church shouldn’t be making culture warriors for Western civilisation. We cannot confuse the collapse of cultural Christianity with the defeat of the gospel of Jesus Christ. The gospel’s sharp edge, its challenge to the powers which hold the world captive, is made blunt when the Church sees culture war as the faithful response to the post-Christian moment.

A gospel for a post-Christian culture doesn’t trade on its core beliefs. But it also doesn’t confuse culture war with Christian witness. What it does is translate the relevancy and radical call of Jesus Christ to post-Christian ears, those who have heard the “gospel” so many times they’ve almost been vaccinated against the real thing. We offer the gospel for post-Christian ears by facing and sharing this moment, not with nostalgic rage and regret, but with open hands and hearts and the name of Jesus on our lips.

No comments yet