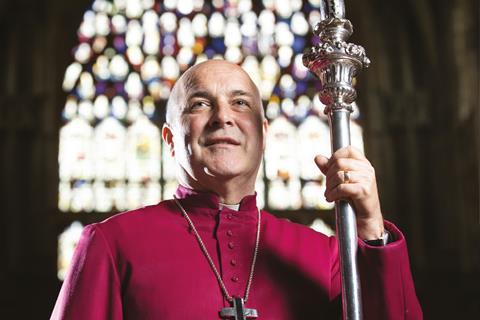

The Archbishop of York says he wants to bring evangelistic renewal to the Church of England

The Archbishop of York is an evangelist. We’re barely two minutes into our conversation when, speaking about the Thy Kingdom Come prayer initiative, he tells me: “We all long, of course, to share our faith.” I’m not convinced every Christian in the land shares that longing (as the old adage goes, ‘evangelism is the only thing equally despised by both Christians and non-Christians’) but Stephen Cottrell, Archbishop of York, is sincere. A significant proportion of the 38 books he’s authored are either about mission and evangelism or, in the case of his newest title, Dear England (Hodder & Stoughton), are aimed at those who don’t yet share his faith.

The 62 year-old might be the second most senior bishop in the Church, but he still remembers what it’s like to be an outsider. Archbishop Stephen wants to make the Church more accessible, and largely avoids Christian jargon in his own writing and speaking. He knows the Church of England has failed to be as outward-looking as it needs to be – “we are failing to connect with young people in the way that we should,” he admits. Change is needed, but exactly what those changes are remains to be seen: “If there was an easy solution we’d have found it by now.”

Cottrell’s ability to naturally converse and connect with all of the Church’s traditions (Anglo-Catholic, liberal, evangelical) is admirable. His own background is Anglo-Catholic, and he is the president of Affirming Catholicism, which styles itself as “inclusive”, values “love friendship and community…irrespective of sexual orientation” and counts former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams among its supporters.

I’m longing to be an archbishop who gives time to the preaching of the gospel

Cottrell’s passion for evangelism is plain then, but he’s not an evangelical. His book makes no mention of any consequences for those who choose to reject the message of Jesus, and so risks being read as a casual ‘take or leave it’ invitation. Dear England is also political in places – and Archbishop Stephen makes no apology for that. The book’s greatest strength is the way it makes a positive and appealing case for the Christian faith. In our information age, where division and controversy are only ever a few clicks away, Archbishop Stephen’s winsomeness is a welcome breath of fresh air.

How did you become a Christian?

My parents definitely would have called themselves Christians, but they weren’t churchgoers. My sister joined the Girl Guides and these were the days when you were required to go to a church parade service once a month. She and a small group of friends liked what they found at the church and started going along on the other Sundays. This pricked my parents’ conscience, who then returned to church, and their whole faith was deeply renewed.

I was actually the last one of my family to dip my toes in the waters of faith. About the same age when many people leave the Church, I joined it. I didn’t have a sudden conversion experience. There’s lots of other contributing factors which I could talk to you about, but you’d probably need to turn this into a 13-part serialisation.

I always find it interesting how some people have a lightning bolt moment of sudden conversion, but for a lot of people, it’s a longer and slower journey to faith…

The research overwhelmingly shows that most people have Emmaus Road experiences, rather than Damascus Road experiences. It’s the experience of a journey where you look back and say: “I didn’t know it at the time, but now I can see that God was always with me.”

When I got ordained in the Anglican Church, my devout Roman Catholic auntie Millie came along. I bet she’d written to the pope to ask for special permission! She told me she had been to Mass every day of her life, and had prayed every day for the conversion of my family. And when I heard that, I suddenly saw my own story in a completely new way. And I do believe that one of the reasons I’m sitting here talking to you is not because of decisions I made to follow Christ, but somehow, mysteriously, it was my auntie Millie’s prayers – even before I was born.

In hearing you speak, and reading your books, I’ve noticed you’re always mindful of those listening to you who may not share your faith. You seem to always have one eye on those outside of the Church. Would you agree with that?

I’m deeply encouraged to hear you say that because that’s precisely how I’ve tried to be, for several reasons. One, because I still remember what it’s like not to be part of the Church. And I’ve always felt that’s given me a little bit of an edge. I hate this language, but you’ll understand what I mean – we’re not very good at recruiting people from outside. But I’m one of the ones who was recruited from outside. I still remember what it’s like to go to church for the first time and how weird it all is. So I try to write and speak about faith in a way that is very mindful of the spiritual longing which is in everybody’s heart, but also just how difficult church culture can be. I think we need to work harder at being more accessible.

When I was a vicar, there was a man who said he wanted to come to church – he definitely didn’t believe but he really liked the community. He asked me: “Is it alright to come on Sundays?” And I said: “Yeah, but on one condition. I don’t want you say the Creed. In fact, don’t say anything if you don’t want to, because I’d much rather you wait until that day you feel you can say it, rather than you just going through the motions.” So he did that. And it was a great day, quite a few years later, when he was baptised and confirmed. That’s what church should be – this gathering together of muddled humanity, exploring what it means to follow Jesus.

Would you describe yourself as an evangelist?

Oh, definitely.

On page 9 of your new book, you actually write the words: “I am trying to convert you…”

Yeah, well, I am! I thought, there’s no point messing about.

I hope I also make it clear that if you choose not to, that’s fine. Because it’s not about me persuading you. It is an invitation, but I am going to offer you the invitation as clearly as I can. I often think evangelism is about removing obstacles which are getting in the way of seeing Jesus clearly.

In your role as Archbishop of York, is there an opportunity for you to ensure the Church puts more time, money, investment and resources into evangelism?

Absolutely. That is my heart’s desire, I get deeply frustrated – if I can bear my soul with you – when too much attention has to be drawn elsewhere.

My heart’s desire, and my aim, is to be a teacher and an evangelist. The question I’ve asked is: God, why have you called me to be the Archbishop of York? And until somebody tells me to go and lie down in a darkened room and hand in my P45 I think the answer I’ve come to is: It’s because of your calling to teach and share the Christian faith. And so I’m longing to be…dare I say this? Well, I will say it. I’m longing to be an archbishop who gives time to the preaching of the gospel, but to [trying] to do it in a way that will be winsome and effective in our culture. And the real danger is that some of the models we’ve used were great in the past, but they’re not effective nowadays. So we need to find new ways of doing it.

And the other thing is, there’s no evangelism which doesn’t flow from your own relationship with God. So the first question is always: “Stephen, have you received the gospel?” And I need to receive it afresh every day, otherwise I’m just sharing my own wisdom, which isn’t really very interesting.

I want to train and mobilise and encourage and focus the Church on being a Church of missionary disciples, so that every Christian feels empowered and equipped to live and share the gospel in their daily lives. And I hope that in my time as archbishop I can make some contribution to the spiritual and evangelistic renewal of the Church of England.

In the latter part of Dear England you talk about everything from Brexit to Trident. That’s helpful in showing people that when you’re a Christian, it should actually change the way you think about all sorts of subjects, including political issues. But isn’t the danger that if the reader perceives you as being partisan – whether to the left or right, Brexit or remain – they’ll think: The archbishop is in such a different place to me politically that I’m no longer interested in hearing his spiritual message?

It’s a really good question. And it’s a question I think I wrestled with when writing the book: Do I stop after the first two parts of the book? Or do I get down into some of the nitty-gritty challenges that the world faces? And I read another book which really helped me understand that I did have to get involved in these issues. It’s called the New Testament.

For those who say politics and religion don’t mix, I just think: You’ve probably never read the New Testament. Because if you did, you would come to a different conclusion; that we have to care about the way the world is ordered. I’ve tried not to be too dogmatic about it, and I don’t think the book follows any one political party or narrative. The book is very strong on the importance of family, which you might say is a right wing way of looking at things. And it does also question whether we should be spending so much money on arms, which might be thought of as being a very left wing concern. But I’m not too bothered about those categories.

So when people say: ‘The Church should be spiritual, not political’, your answer is: ‘We don’t have to choose. They’re both intertwined and they’re both important’?

Absolutely. You know, I did an interview with The Observer, which I thought was a very fair, good interview, and I really liked the reporter, but she did say: “I really like some of this stuff about our identity and our belonging and how we need to live in community, but I just don’t get all this God stuff.” I said: “I get it, but for me, there is no separation here.” And I also hopefully challenged her by saying that those values and ethos, which we can all agree on, don’t exist in a vacuum but flow from beliefs and doctrine. And the danger is that the world wants the values and the ethos, but it doesn’t want the belief and the doctrine, and you can manage for a while without them, but in the end, you start losing your moorings as a culture.

People want the kingdom without the king.

Yeah, exactly. The whole book is about repentance. I just don’t use the word until the end. The whole book is actually about saying the problem is the human heart. My diagnosis is the world needs a heart transplant – that’s another way of saying you need to be forgiven, but I don’t use that language, I use the language of a new heart. But really, what I’m saying is: “You need to repent”, because part of what happens when you repent is that you’re given a new heart and a new spirit. If we could solve all this through our own cleverness and wisdom, then we would have done it. But, in fact, our own cleverness and wisdom has led to some horrors in the world. The Christian way starts with the human heart, and says that’s the first thing to change. And only God can change hearts.

I do get deeply distressed by the things I read about myself on social media

The book makes a positive case for why you might want to embrace God and have your heart transformed. But the questions I’m left with at the end are: What happens to those who reject that message? Are there any consequences?

Yes, I think there are, though, thankfully, I’m not the judge. So I leave that to God. I’m clear that if I choose to wilfully reject that which I know to be right and true and good, then I have to accept the consequences of that. But wilfully rejecting and never having heard are not the same thing. And so my energy and effort goes into helping people to hear the good news clearly, so they can make a response to it. I feel my job is to hand out the invitations. If somebody chooses to reject the invitation, it’s not my job to judge what happens to them.

What does an average day look like for you?

At the moment, like everybody, my life is on Zoom. I think when we get beyond Covid, I will be much more out and about. But the heart of my daily life, and the most important thing I do each day, is prayer. I consider myself a beginner in the spiritual life, so I don’t pretend to be anything other than that. The daily discipline of prayer, for me, is rooted in what we in the Church of England call the Daily Office, which just means the Psalms and the scriptures.

The world needs a heart transplant…and only God can change hearts

The heart of prayer isn’t about what I say to God. It’s about what God says to me. That means I arrive at a point where I’m open to God’s will and the knowledge of God’s love for me; to know that I’m the beloved of God, and that he longs for me to share that knowledge of our belovedness with everyone.

How do you decide what critical voices to listen to and learn from and which – to use the internet terminology – are just trolls?

It’s a really good question, because I am the Archbishop of York, but I’m also Stephen, who’s frail and who gets things wrong, and who sometimes puts my foot in it.

I do get deeply distressed by the stuff I read about myself on social media. I try to be disciplined about either not reading it at all or just trying to quarantine it and not take notice of it. But I am troubled by what social media has done to human discourse, and the casual way in which we can be so, so rude to each other, even in Christian community. I want to live in a world where I believe the very best intentions of others, not the worst.

What do you hope your legacy will be?

This is going to sound like a terribly pious answer, but I think it’s the truth: “I must decrease, he must increase” [see John 3:30].

You can’t write your own obituary but I hope it might say: “98th Archbishop of York gave his time to teaching and sharing the gospel.” I’d love it if people came to faith as a result [of my ministry] but I don’t think I’ve failed if they don’t, because it’s not about success or failure, it’s about faithfulness and fruitfulness. So my job is to be faithful. And if the Lord of the harvest brings people to faith, then I will rejoice. But if he doesn’t, I’ll carry on trying to be faithful.

Thy Kingdom Come is a global prayer movement that invites Christians to pray for more people to come to know Jesus. It runs from 13-23 May. thykingdomcome.global

To hear the full interview listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on 22 May or download The Profile podcast