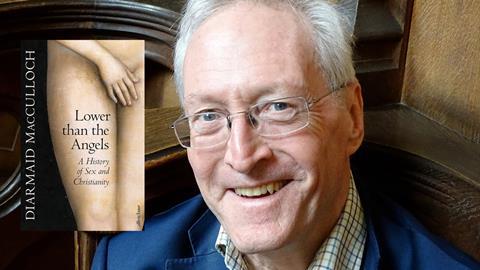

The acclaimed historian’s new book Lower than the angels: A history of sex and Christianity is not a light read. But it’s a useful contribution to ongoing debates, says our reviewer

This is another ‘big book’ from the academic, historian and television presenter, Diarmaid MacCulloch.

Spanning 600 pages and interrogating social, biblical and cultural attitudes towards sex and Christianity from Ancient Greece to the modern day, this is no casual or superficial undertaking, and not a light read.

MacCulloch is known for approaching huge topics, carrying out tireless research and offering his audience a new slant on what might previously have seemed familiar and understood. In what is a dozen books now, his forensic accounts of the Tudor period and ecclesiastical history through millennia have engendered an enthusiastic following.

In person he cuts a dashing figure in his linen jacket, with sparkling eyes and a wry smile, and is considered a charming and engaging speaker and writer. In recent years his notable titles have included Thomas Cromwell: A Life (700 pages) and A History of Christianity: the first three thousand years (1,200 pages).

“There’s no point in selling it short,” he has said of his comprehensive approach to his subjects. “I’m not going to cut corners.” And, recalling his supervisor at Oxford, the great Tudor historian, GR Elton, MacCulloch has always sought to follow Elton’s philosophy that “you must passionately seek the nearest thing to the truth you can find, and constantly test it.”

Considered a liberal, MacCulloch calls himself “a friend of Christianity”. Though ordained, he chose not to practise due to the Church of England’s view on homosexuality. Because of this, it would be easy to assume that he has produced this book slanted by his own life experience and perspective, but that would be to do him a disservice. He instead approaches the subject with scholarly insight and presents the arguments with an objective and dispassionate, though contemporary, viewpoint.

The book, despite its size, scope and density, is very readable and there is a warmth and immediacy to MacCulloch’s writing. But it is worth approaching slowly and studiously, and to return to as a reference guide. There are extensive notes, index and further reading suggestions, so it’s a formidable resource.

the historian’s reminder of things forgotten is hardly ever welcome in the religious sphere

It is divided into five sections, and pursues the Christian faith chronologically as it is manifest through the church, society and believers. His early chapters provide a fascinating and useful context, from the Greeks to Judaism, Jesus’ ministry and Paul and the early Church.

MacCulloch goes on to chronicle and celebrate the complexity and contradictions of past generations and it proves an enlightening reminder that life wasn’t necessarily better or clearer in earlier times.

We might think that we can look to the past, to our “doctrinal inheritance” to lead us as we are faced by current gender issues, “since those lie beyond Christian theological constructions of reality” but there are many examples in Christian history of gender or sexual ambiguity, he tells us.

MacCulloch looks fleetingly at the teaching of Jesus. He simply makes the point that Jesus had nothing to say about homosexuality, and that hypocrisy and inhospitality were more concerning to him than sexual behaviours. There is less analysis of the role of women through the ages than might have been expected. And there is no clear conclusion at the end of each section. Instead, there is a paragraph about what we’ll be discovering in the next period of time. This is effective in encouraging you to keep reading, but any interpretation on what we can learn or take away from each period is largely absent. What’s more, the final chapter is ‘a story without an ending’. There is no conclusion, MacCulloch says, because the story isn’t over.

It’s an important work. As MacCulloch says, “In the last half-century sex and gender have rapidly become more instrumental in internal church conflict than at virtually any time over the last two millennia of Christian life…Churches have found it agonizingly hard to react coherently to questions they had not previously asked, let alone answered.”

It’s clear though, as he says, “the historian’s reminder of things forgotten is hardly ever welcome in the religious sphere”. The motivation behind certain elements of the faith are intrinsically linked to social and cultural pressures of the time, so how much do we adhere to them today when life is so radically different?

In these difficult, confusing times it feels as though we want a simple message to live by more than ever. However, this book urges us to pay attention to the complexity and contradictions in the history of Christianity. We may not find “a single Christian theology of sex” but this does bring a greater appreciation of the social and historical precedents of the Church.

Undoubtedly readers will feel better informed on closing this text and the book is a welcome addition to the debate of sexuality today and how the Church can better address and clarify its position and arguments. A more concise account might reach a wider audience.

Lower than the angels by Diarmaid MacCulloch (Allen Lane) is out now

No comments yet