The Booker Prize winner follows the lives of six astronauts orbiting earth. This short book with little dialogue or plot is peppered with references to God, says Joy Summers. What hope can Christians find in the deep questions that it asks about life and the universe?

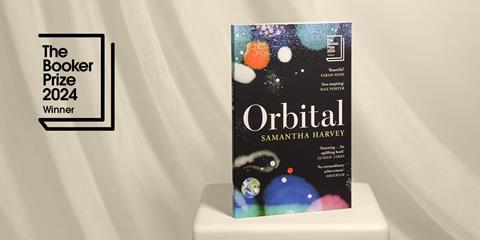

Each year I pick a title from the Booker Prize short-list to read. It’s a game I play; a private lottery to see if I coincidentally choose the winner. This year I chose Orbital by Samantha Harvey (Vintage). The novel, which went on to become the 2024 winner, has little plot, character development or dialogue, yet I was gripped by it.

Why did it become so popular and what does it say about the world we inhabit?

Extraordinary ordinary

The novel follows the lives of six astronauts orbiting earth, recounting their mundane rituals in an extraordinary setting. As they orbit the earth multiple times a day, they must choose to hold on to a time-bound, earth reality. Describing the confusion of their senses and rigorous schedule, the reader gains insight into the character’s thoughts and anxieties.

Alongside awe of their view of earth, there is a shifting sense of disconnection with their home planet. The death of a parent and the anticipation of meeting other astronauts remind them of their painful sense of removal from home and humanity. Despite having trained their whole lives to leave earth, the alienation they feel is still bitter-sweet.

Connection and longing

The novel is, primarily, the means to a philosophical end, discussing the desire for connection and humanity’s longing to be known. The universe is described in bleak and lonely terms.

One crew member wonders about other life forms: “Could they see into a human’s mind? Could they know she was a young woman in love?” The potential of a creator God is proposed as they reflect that they “could almost believe earth came from God and could mean something” but the notion is quickly dispelled.

Shaun, the Christian astronaut, is not mocked. Instead, his beliefs are treated as completely irrelevant

Though the book debates and debunks a creator God throughout, there are multiple biblical references that seem amusingly incongruous. God is suggested and denied in the text, but unconsciously referenced over and again, as if the author is unaware of his presence even in her own words. The world is described as a “holy ghost”; a “huge Bethlehem light” is used to describe a star - but no mention is made of what that original Bethlehem light was announcing.

One person talks about how humans could be replaced by robots, then asks: “But what would it be to cast out into space creatures that had no eyes to see it and no heart to fear or exult in it?” It is so close to an argument for a loving God that desires relationship, but the idea is not developed, and questions are left hanging.

Talking truth

Orbital often seems to approach truth then quickly veer away. When discussing the photograph taken of the first men walking on the moon, it comments: “Every single other person currently in existence, to mankind’s knowledge, is contained in that image; only one is missing, he who made the image.” Referring to the photographer, the sentiment has such an obvious parallel with the astronaut’s view of creation that persists in ignoring the creator.

In another passage, an astronaut reflects that humankind “didn’t ask to inherit an earth to look after, and we didn’t ask to be so completely unjustly darkly alone.” But how can our aloneness be unjust without a creator to blame?

Orbital is a book that states both unequivocally and yet uneasily that there is nothing higher than us to which we can look. The lights that shine at night are described as “the way the planet proclaims to the abyss: there is something and someone here.” This sentiment inverts the belief that “the heavens declare the glory of God” (Psalm 19:1).

This turning towards oneself is, however, unsatisfying. “What can we do in our abandoned solitude but gaze at ourselves? What else is there? To itch with a desire for fulfilment that we can’t quite scratch.” The book criticises the “forever gazing at ourselves” while asserting there is little alternative.

In one especially blatant replacement of God with man, a photo of Krikalev, a revered astronaut, is described as looking out “from the photograph as a god looks on its creation…his smile seems more and more vaunted and more and more godly. Let there be light, he seems quietly to say.”

The faith thermometer

Christianity is often ridiculed in contemporary fiction, but something very different happens in Orbital. Shaun, the Christian astronaut, is not mocked. Instead, his beliefs are treated as completely irrelevant. This is a fascinating thermometer of how faith is viewed. One colleagues ponders: “Is Shaun’s universe just the same as hers but made with care, to a design? Hers an occurrence of nature and his an art-work? The difference seems both trivial and insurmountable”.

Nell wants to ask Shaun how he can be an astronaut and believe in God, but knows Shaun would reply by asking how she could be an astronaut and not. Nell clearly thinks it would be pointless sophistry to engage in discussion, so none takes place.

The novel is, primarily, the means to a philosophical end, discussing the desire for connection and humanity’s longing to be known

In turn, Shaun accepts the most basic tenet of the evolutionary survival of the fittest over a biblical perspective of us being “fearfully and wonderfully made”. The only believer in the novel decides there’s no story beyond humans on earth. This moment is not depicted as a crisis of faith but as something that doesn’t even affect his beliefs. It posits that we can have faith but continue believing that everything starts and ends with us. The writing is not an attack on belief but total indifference to something viewed as harmless and inconsequential.

Ultimately, Orbital describes a chaotic universe in which humankind is so far from central to God’s plan and of so little significance as to be considered a blip, quickly forgotten. We are not the creatures on which God has laid his affections, but something barely worth a mention. From its early pages, the novel asserts the insignificance of events and existence: “There is no centre, just a giddy mass of waltzing things”.

Shelter from the storm

There is one brief return to earth, in which people are sheltering from a storm inside a church. It is an obvious metaphor: we search for security in faith. When forced physically and metaphorically into a corner, even those without faith revert to an almost animistic hope of rescue.

As Tim Keller said: “All the long and complex history of earth’s religions, pagan worship, and human philosophy is bound up with this insatiable thirst for God” but when it is within reach, it is lost.

The knowledge that the characters gain from their experience in space is that they’re “humans with a godly view and that’s the blessing and also the curse.” Isn’t this exactly the result of the fall, experienced by Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden?

The novel is bookended with near acknowledgements of God. The astronaut’s initial view of earth evokes “a sense of attention and servitude, a sort of worship” and finally “a sense of gratitude so overwhelming that there’d be nothing they could do with or about it, no word or thought that could be its equal.”

Yet despite coming so close to revelation, Orbital is a book that depicts humanity searching for knowledge and then responding to it by turning its back on the ultimate truth.

No comments yet