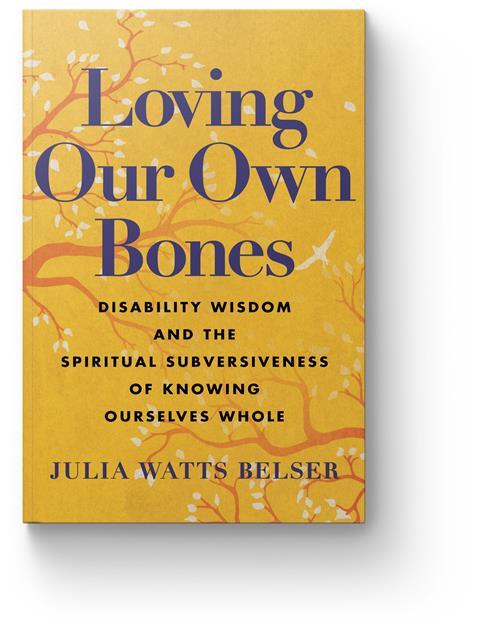

“Everything I know about God comes through these disabled bones,” writes Julia Watts Belser, historian of ancient religion, Jewish rabbi and disabled activist. In her latest book, Loving Our Own Bones (Hodder & Stoughton), these three strands of her identity combine in a provocative and scholarly commentary on ableism in the Jewish Bible.

The introduction sets out her stall as a feminist, queer, anti-ableist Jewish theologian who does not feel the need to defend scripture. That description alone will probably either excite you or repel you, depending on your theology, or age. Before serving the meat of the Bible commentary, we have a dense starter on the nature of disability and ableism. Ableism is far broader than “being mean to disabled people”. It is the whole mess of political and cultural structures that seek to exclude, dehumanise, silence or kill disabled people. “You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism,” she claims, because it encompasses valuing a person solely for their economic productivity. I’m still chewing on that one.

The main section explores a number of passages that ministers dread preaching about if they have disabled people in their congregations: Leviticus 21, which lists all kinds of disabilities, impediments and ‘blemishes’ that exclude priests from serving; Miriam’s leprosy; Leah’s plainness; Jacob’s limp; and Moses’ speech impediment, which God set in place.

Her chapters on Moses were my favourite. She explains how he was forbidden from entering the Promised Land after he struck a rock to bring out water instead of speaking to it, as God has instructed. Watts Belser first reflects on this incident from God’s point of view. As a disabled person, she knows the frustration of needing to ask others to do the things it would be quicker to do yourself, and she sees God’s understandable anger when his instructions aren’t followed.

She goes as far to claim: “As far as I can tell, God can’t pick up a single stone without a human hand to lift it.” While this is provocative hyperbole, it’s a reminder that although God is powerful, God chooses a kind of “intentional dependence” on human actions, which the disabled experience illuminates.

She then looks at Moses’ exclusion from the Promised Land with poignant examples of her own disabled exclusion from Sabbath meals, synagogue meetings, outings with friends, connecting her own longing with Moses’. She then caveats her own point: even pity for disabled people can be problematic and is a narrative that has been weaponised to dehumanise disabled people. It is a delicate balance.

Watts Belser uses a surgeon’s scalpel in evaluating these stories and readings, looking for the good, exposing the pastoral damage. She will dialogue with rabbinic readings, then dialogue with her own conclusions, always questioning, never settling for simple resolutions. Despite initially declaring she wasn’t out to defend scripture, she certainly doesn’t dismiss it, describing her process of study as “always winnowing, winnowing and gleaning”, seeking the loving God “whose signature is written into my bones”.

As a disabled Christian and pastoral theologian, I valued this book as an original offering with plenty of gems – for example, I had no idea that there is an ‘origin story’ in Jewish midrash that Isaac’s blindness was caused from the trauma of being offered up as a child sacrifice. In the chapter on the exclusion of ‘blemished’ priests, I loved learning how rabbinic thought has grappled to become less ableist over the years. Her more personal reflections on the beauty of the disabled body were compelling, and her unashamed, dogged questioning of ableist interpretations of the Torah was a fascinating process to follow. It’s academic writing, but the Bible chapters flow easily.

While this is decidedly an important contribution to the field of disability theology, written with nuance and depth, it left me wondering about its audience. Some evangelicals may feel queasy at the way she describes her relationship with the Bible. Though she tends towards redemption, she’s unafraid to criticise not only the text but sometimes also the character of God. Even Christians familiar with academic theology and intersectionality may recoil from her description of Jesus, which comes close to portraying him as an insensitive faith-healer who invades the space of disabled people and connects their disability with sin. This Jesus chapter, which is the weakest, highlights that this is not a devotional, nor a Christian book. It merely invites Christians as sympathetic witnesses to a disabled Jew’s rabbinical wrestling with the Bible text.

Many of her lines of thought I didn’t agree with, but all were fascinating and made me think deeply. Watts Belser describes the Bible not as a “book of answers” but “a book of haunting questions”. The same can be said of hers, which I hope she would recognise as a compliment.

No comments yet