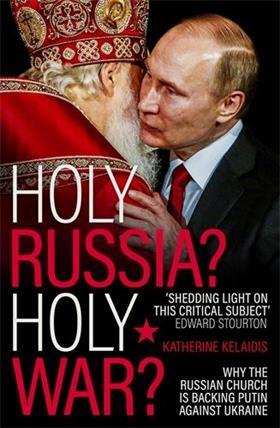

The Ukraine war is not only a geopolitical war with Russia, but actually a war within Orthodoxy itself. So argues Katherine Kelaidis in her new book Holy Russia? Holy War? Her rather fatalistic assessment of the situation is tinged with hope for change, says Paul Valler

This is a politically charged expose of the Orthodox Church and its role in Ukraine, opening our Western eyes to an Eastern understanding and historical framing of the war.

Katherine Kelaidis reveals how Moscow’s chief bishop has become, in her opinion, Vladimir Putin’s chief propagandist.

Kelaidis spends the first part of the book tracing the complex and painful history of the Orthodox Church. Her deep understanding of this early history is interesting, but sometimes packed with too much detail. She explains that although originally headquartered in Constantinople (modern day Istanbul where it continues today), as the Orthodox Church grew eastwards, a second centre was formed in Kyiv. But as political power shifted to Moscow, the first bishop of Moscow acquired the ecclesiastical territory that had once belonged to Kyiv. So in Orthodoxy, where once Kyiv ruled Moscow, now Moscow rules Kyiv.

This clerical tension in the church dramatically increased in 2018, when the Ukrainians asked the ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople to establish an independent Orthodox Church in Ukraine, free from the Moscow Patriarchy. Kelaidis shows through recounting this history that the Ukraine war is not only a geopolitical war between Russia and the West, but actually a war within Orthodoxy itself. Recent crackdowns by the Ukraine government against the Moscow-backed Ukrainian Orthodox Church, are because they are suspected by many to now be operating as a cover for Russian espionage.

Kelaidis is particularly scathing about Moscow’s chief bishop, Patriarch Kirill, who grew up in the era of the Soviet Union, and is widely believed to have previously worked for the KGB. Kirill is an active supporter of Putin and of the ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. His words carry weight, because Russians largely identify as Orthodox, although church attendance is low. So when Kirill says that "Russia and Ukraine are brothers like Cain and Abel" he reframes the Ukraine war as a civil war, not the invasion of a sovereign state. This goes to the heart of a fundamental difference of perception between Russia and the West. Kelaidis argues that Kirill’s actions are motivated by the demands of cut-throat geopolitics and nothing else, which gives the lie to any air of respectability or independence the Moscow-based Church may try to project. She proposes that Patriarch Kirill should be sanctioned, something the UK Government has now done.

The book is somewhat disjointed, because after starting in a historical narrative style, the author's writing abruptly changes gear to chapters which appear to be recycled political blogs

Several chapters then widen the scope of the book by showing how the influence of the Russian Orthodox Church is being used in other global territories to further Russia’s agenda, citing examples in Moldova, Cyprus, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Korean Peninsula. All this, Kelaidis says, is because Patriarch Kirill holds the view that the church survives and influences by accommodating the state. A philosophy that has inevitably created tension with many other religious leaders – even including some within Russia itself. Apparently, the Pope recalls saying to Kirill: “Brother, we are not clerics of the State, we are pastors of the people.” This awkward dialogue has led to suggestions that the Russian Orthodox Church should be expelled from the World Council of Churches. But Kelaidis argues that could backfire, because Kirill and Putin would use any expulsion to further the story that Russia and the traditional values of the Orthodox Church are again under attack from a hostile, decadent West.

The book is somewhat disjointed, because after starting in a historical narrative style, the author's writing abruptly changes gear to chapters which appear to be recycled political blogs. These are clearly written to make the case against Putin and Kirill, with Kelaidis obviously promoting the West’s perspective on the war. She rates it unlikely that a lasting and real peace will come any time soon, because the historical and cultural circumstances that have allowed Putin and Kirill their power remain largely intact. Nevertheless, her rather fatalistic assessment is tinged with hope for change, and the book finishes by bizarrely reverting to history, with examples of two Orthodox saints to back up her hope. These sudden shifts in perspective and style make the book feel like a repackaging of previous material.

Beyond the Ukraine war, there is surely a general learning here from Kelaidis; the grim reality of dangerous clerical power in the organised church. Whenever church and state work to a common political agenda, clerical power can so easily become toxic and damaging, and corruption inevitably follows. Kelaidis’ sad description of the existential crisis now engulfing Orthodoxy, shows how this misuse of power, and internal church conflict, is damaging not just the church itself, but also the peoples and nations in which it lives. This is indeed a sobering book, that should make us all wary of selfish power exercised by the organised church in any jurisdiction – especially when that church is wedded to the state.

Holy Russia? Holy War? by Katherine Kelaidis (SPCK) is out now

No comments yet