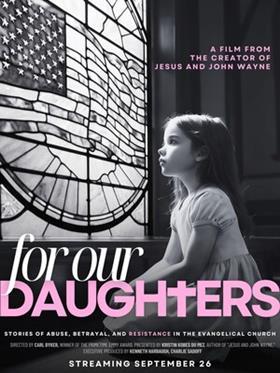

A new documentary attempts to explain how abuse has been allowed to fester in US evangelical churches. Greg Garrett says For Our Daughters is urgent and important, and will challenge Christians to return to the way of Christ

I have two daughters. If one of them told me that she had been sexually assaulted, I would be outraged and would thoroughly support her in pursuing justice.

But imagine if, instead of outrage being directed at the rapist, it was directed at the victim. Then you will understand the urgency of Kristin Kobes du Mez’s new documentary For Our Daughters, available to view on YouTube.

I was raised in a Christian culture where men were the unquestioned heads of families and male pastors were the unquestioned heads of their churches. For Our Daughters tells the story of Christian communities where men in pastoral roles have assaulted children and women and, instead of being called to account for those crimes, they have been restored to ministry. Meanwhile, their victims have been ignored or even called out for being an “occasion of sin.”

The film shows how Christian purity culture assigns the entire weight of human desire to women, who are not only told to behave with modesty to avoid inflaming men’s lust, but to fully accept the mastery of the men in their lives - fathers and pastoral figures particularly. It’s a recipe for abuse - and the avoidance of addressing the root causes of such abuse in the Church.

For Our Daughters is powerful and painful. We hear from survivors and activists Tiffany Thigpen, Jules Woodson, Rachael Denhollander and Cait West, as well as hearing about the more than 700 survivors identified during journalistic investigations into the Southern Baptist Convention.

The honesty and courage of these women is palpable, particularly when they speak about their fears for their own children in the Church. They feel called to speak out as adults, they say, because young survivors shouldn’t have to bear the weight of the public condemnation that is endemic to telling the truth in these settings.

By contrast, we see how men who offer facile public apologies are restored to ministry without legal or even lasting vocational consequences.

Those advocating for the survivors, “are not calling for a departure from Christ, but rather a return to who Christ really is.”

Du Mez herself appears in the film to offer historical and cultural insights. The author of Jesus and John Wayne continues to preach against the dangers of male domination, describing how men in positions of power have been allowed to commit all sorts of atrocities without real consequence. It is this hierarchal mode of thinking, she notes, that helps explain a puzzling question: How can the same evangelical Christians who once insisted that a leader’s character matters offer their support for and defence of Donald Trump, an adjudicated sexual offender?

Former American gymnast, Rachel Denhollander, was the first person to speak publicly about being assaulted by serial abuser Larry Nassar, but she had previously been molested as a seven-year-old in her church. She saw the way that the Church often excuses - or quietly deals with - rape and sexual abuse. “When you’ve created a culture where manhood and womanhood is defined by submission and authority,” she says, “you’ve created a culture where authority goes unchecked and easily becomes abuse. And men think they can get away with abuse because they actually can get away with it.”

The great irony of Christian institutions excusing abuse and abandoning the abused is that it is anathema to Christian teachings. Denhollander herself makes this argument at the film’s close: Those advocating for the survivors, those seeking justice, “are not calling for a departure from Christ, but rather a return to who Christ really is.”

Du Mez explains in the film’s promotional material why she felt called to make this documentary: Three conservative evangelical women sought her out, thanked her for her writing, and asked how they could help. “It’s too late for us,” they told her. “We’ve made our choices, and we can’t walk away from the lives we’ve made. But we want something different for our daughters.”

For Our Daughters may not surprise those who have lived within these cultures, but perhaps in focusing attention on a searing injustice, it will inspire necessary action. Du Mez hopes the documentary will call us to care for the daughters of those three women - and for all our daughters; to be the change we want to see in the Church and in culture.

May it be so.

For Our Daughters is available to view now on YouTube

No comments yet