This 113-minute feature film is controversial from the outset. Even the opening words which appear on the screen – “inspired by historical events” – will likely cause upset.

Did the Virgin Mary really appear to three children in rural Portugal in 1917? Did she correctly prophesy the end of the First World War and the beginning of the second? Was this followed by a miracle, apparently witnessed by tens of thousands, where the sun careened towards earth before zigzagging back into position? Atheists (and Protestants) answer a firm ‘no’ to all of these questions, but for Catholics today, the events at Fatima were the real deal, and thousands of pilgrims still flock to the site.

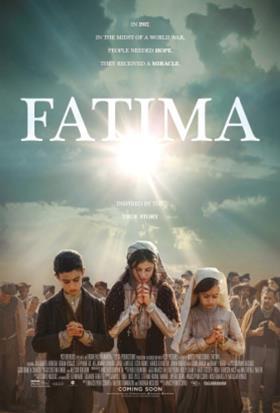

Directed by Marco Pontecorvo (Game of Thrones, Rome, Letters to Juliet), Fatima dramatises the claimed Marian apparitions and miracles, with the majority of the film following the young lives of siblings Francisco and Jacinta Marto, and their cousin, Lucia. Despite being accused of lying, and almost begged to recant their testimony by parents and bishops alike, all three children stick to their stories, and as word spreads that Mother Mary is appearing regularly to these children and revealing secrets to them, the crowds swell and the children (or “seers”) become local celebrities.

Sadly, the action is rather drawn out onscreen and the sub-plots lack emotional depth. The film partially redeems itself by regularly flashing forward to 1989, when Lucia (now Sister Lucia, an elderly Catholic nun) is being gently interrogated by a deeply sceptical author, Professor Nichols (Harvey Keitel). At one point the professor raises the issue of how culture appears to dictate what kind of heavenly vision a person may receive. In other words, Catholics tend to have visions of Mary and Protestants always claim Jesus has appeared to them while Muslims report visions of Mohammed. “Doesn’t that seem strange to you?” he asks. “No,” answers Sister Lucia. “But if I follow your logic,” the professor continues, “either there are multiple divinities, or it is the unconscious which translates each person’s desire to meet the divine in images that belong to their particular culture.” Sister Lucia replies: “You call it ‘the unconscious’. I call it God, who in his infinite wisdom manifests in the form that we expect, in order to help us understand better.”

Whatever you think of their respective explanations, it is these sparky yet respectful discussions between sceptic and believer that make the film worthwhile, and will provide audiences with plenty of fodder for discussions once the credits roll. Ponder, for example, Sister Lucia’s pithy phrase, “faith begins at the edge of understanding”.

This is not an especially gripping film. But the producers have at least avoided the pitfalls of making a piece of Catholic propaganda on the one hand, or a sneeringly secular film on the other. What viewers are left with is a mature, thought-provoking representation of a story that carries great meaning for millions around the world.

Fatima is released on 25 June. For more information see fatimafilm.co.uk